How Faith Connects to Slum-based Schooling

The Church and the schools

Christians have historically been on the forefront of educational development. Mindful of both Jesus' extraordinary care and concern for children, they have labored to grow students intellectually, spiritually and socially, and to foster similar growth in society. To do anything less was to put an almost insurmountable stumbling block (Mark 9:36-42) in the path of that child.

Robert Littlejohn and Charles Evans underscore education as the cultivation and application of wisdom for the world in which one lives, saying:

"To be of any earthly good, a person must understand the world around him and recognize what it needs. He must be capable of discerning between what is true and good and beautiful in society and what is not, and he must be empowered to make a difference through perpetuating the former. In short, he requires wisdom and eloquence. Our activist must understand himself to be the inheritor of a dependable tradition of wisdom that he has the responsibility to steward and to articulate to his contemporary world. (Wisdom & Eloquence, p. 18)"

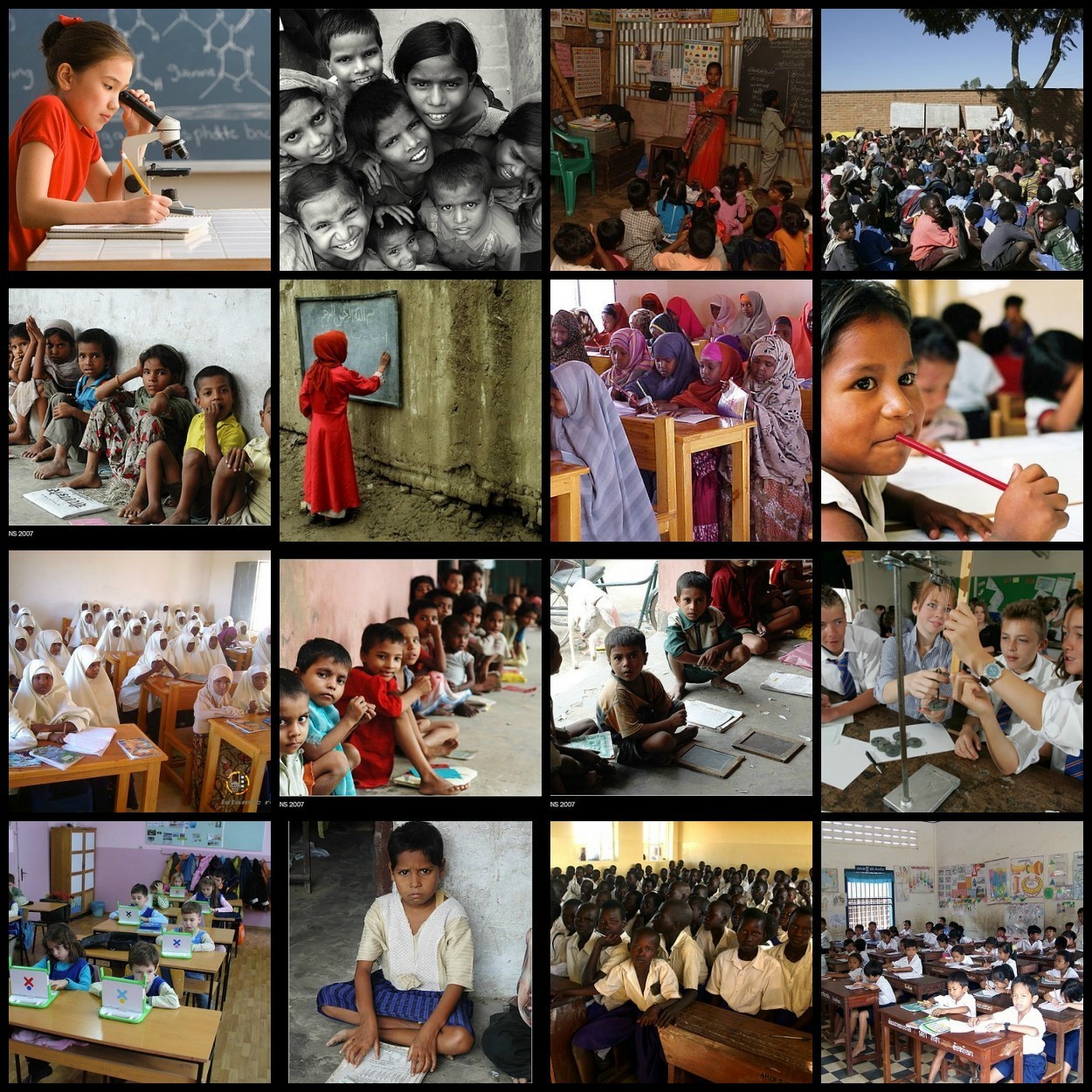

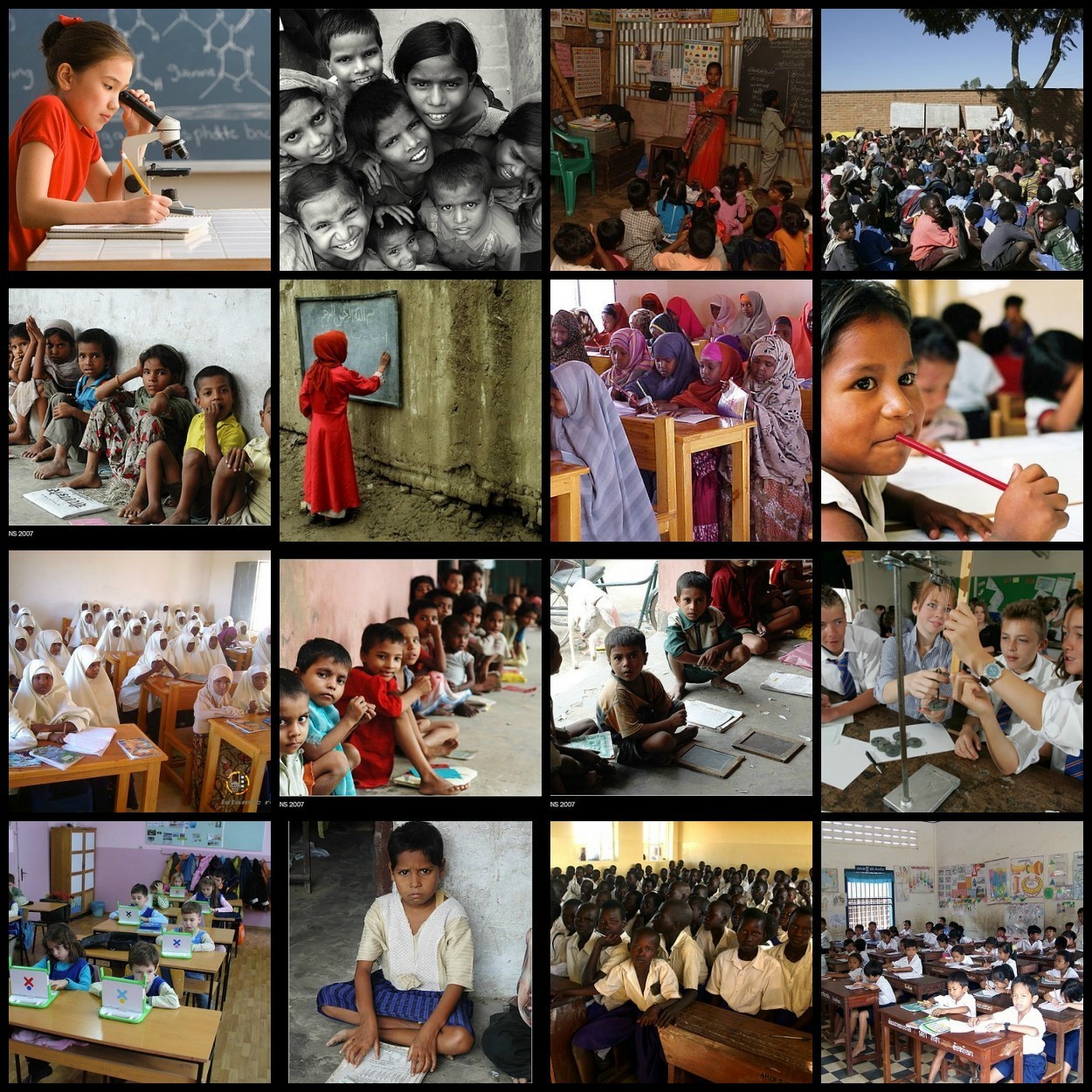

For most children, adolescents, and young adults of the developing world, public schools have been the primary route for full participation in the economic, political, and social life of their communities. More recently, private schools have also provided an additional educational option, especially within slums. Schools, both public and private, teach children how to read and think; to be able to read (including reading the Bible) and compute; and in some cases to design, produce, and sell. Schools enable students to develop a positive self-esteem as their God-given talents are recognized and nurtured.

From earliest times, when the church first pushed out into the world, people have asked: What has Jerusalem (Church) to do with Athens (society)? Some answered, either fearfully or simplistically: "Nothing at all." Others answered (in the name of ‘being relevant’): "Almost everything in every way." The religious disjunction between pietist-withdrawal and cultural-accommodation is still with us today, in our private and academic lives, and also church-sponsored activities, including the schooling of the young.

Two things are necessary if Christians are to relate their personal allegiance to Christ to a public commitment to quality schooling among “the least of these.” They must, first of all, be better informed about school realities in poor communities. Then they must work together with school leaders, parents, and children to support and strengthen the schools. This is where local churches are challenged to be a catalytic agent for the educational development among the urban poor. In practical terms, urban poor congregations can:

-

Form special working groups to learn about educational needs and local school issues.

-

Honor teachers, both within and outside the congregation, as role models for young people.

-

Collect books and organize literacy programs.

-

Advocate for the broad availability of all age-appropriate materials and books in public and private school libraries.

-

Encourage pedagogies that broaden students' experiential understanding of human and natural life.

-

Initiate programs in partnership with local schools to provide after-school assistance and enrichment.

-

Provide parenting classes to emphasize the special responsibilities of families to schools and school-aged children.

-

Support thoughtful reform and innovation in local schools to improve teaching and learning at all levels, and especially to end unjust educational disparities between rich and poor.

-

Hold public and private schools accountable to high quality education.

-

Encourage the development of local educational centers that are small, personal, creative, and caring.

Public theology and slum schools

Public theology strives to uncover the theological issues that underlie human culture, society, and experience, including schooling. It “points towards a wider and deeper strand of theological reflection rooted in the interaction of biblical insight, philosophical analysis, historical discernment and social formation” (Max Stackhouse). When applied to slum schooling, public theology raises questions that precede practical concerns over how the school is organized, the classroom managed, and the curriculum structured. It’s focus, first and foremost, is on the school's “religious” vision—that is, with the prior what and why questions. What human and community development goals energize the school? What life orientation or “calling” is reflected in those goals? Why does any of it matter?

MATUL students do not live and learn in a vacuum. Rather, they operate within the frameworks of their native assumptions, traditions and habits, the culture of their host communities, and the culture of the institutions (e.g. churches, health clinics, schools) in which they serve. Their scholarship develops within this broad and complex picture of reality. Subjects like “slum schooling,” then, cannot be reduced to just their theological dimensions (i.e. God’s revelation according to a particular religious tradition). Most of our work will be to acquire an intimate and accurate understanding of schooling within the context of urban poor community life, and to do so according to the standards and perspectives of informing disciplines (e.g. urban sociology, anthropology). That is why “good Christian scholarship may be virtually indistinguishable from scholarship done by anyone else” (Robert Wuthnow).

At the same time, Christian values and commitments should make a difference in the moral agendas that shape our scholarship. The term “public theology” describes a way of doing theology with a focus on issues of public concern. Within the MATUL program, theology attempts to “go public” by addressing critical issues facing the urban poor, including: public health, land rights, human rights, economic development, and education. Dialogue is an essential method in the “public” character of the MATUL pedagogy, which is what students are inserted, not just in private churches, but also in public clinics, schools, and advocacy organizations. Through focused reading, video viewing, and a course internship, students’ “public” dialogue extends to other scholars, community practitioners, policy makers, and local residents, especially those whose voices are often not heard but who feel the impact of public policy on their lives.

How might someone manifest their faith within the context of both the MATUL program and the present course (TUL555)?

1. Lifestyle solidarity. One of the MATUL program’s central assumptions is that insight and understanding is revealed, not through physical distance and emotional objectivity, but by sharing in a significant way the experience of being marginalized, un-resourced, and perhaps even mistreated—i.e., through solidarity. MATUL students are expected to relocate to program sites within select global megacities, find housing with local families either in or adjacent to slum communities, and engage in intensive language learning for three to four months prior to beginning formal coursework through the hosting institution. Students embrace a style of being that puts them in direct and reciprocal relationship with those whose reality they wish to comprehend. Solidarity with residents becomes the basis for learning from them, “to receive,” in the words of Henri Nouwen, “the fruits of the lives of the poor, the oppressed, and the suffering as gifts for the salvation of the rich.” This is only possible when the primary bond of the knower to the known is one of empathy and love rather than dispassionate logic.

Of all the great Christian doctrines, it is perhaps the Incarnation that has been most neglected in its pedagogical theological significance. Jesus didn’t remain in a sequestered religious or cultural “bubble,” nor did he conduct “mission trips” from the heavens to earth. He became little, weak, minority, vulnerable, dependent, and misunderstood. He entered the world’s pain, problems, and thought systems through direct, firsthand encounters that involved costly identifications (Philippians 2:6–8; Matthew 20:26–28).

At least six core theological values flow from this “radical esteem for the incarnation.” They help inform a “public” faith-based pedagogy within the educational design of the MATUL program and the Educational Center Development course:

-

Self-limitation (vs. power preservation). Students take on to themselves some of the conditions and constraints of temporal existences radically different from their own.

-

Embodiment (vs. detachment). Students are placed in direct, physical relationship with slum life rather than merely taught about it.

-

Involvement (vs. distance). Students make an experiential commitment to narrow the distance between themselves and those who are “stranger” within their host communities.

-

Collaboration(vs. independence/exclusion). Students relate to community families and associations (e.g. schools) in ways that are caring, mutual and reciprocal, and that reverse the traditional relationship of outsiders dispensing knowledge and time upon a “dependent” community.

-

Responsibility (vs. passivity). Students re-imagine the ultimate purpose of their education, away from the mere acquisition of knowledge, marketable skills and personal security, and toward the application of those competencies in the transformation of poor communities.

-

Redemption (vs. domestication). Students imbibe a simple ethical imperative: that they are here to make a difference, to mend the world, to make it a place of justice and compassion. Faith is not an acceptance of the status quo, but a protest against the world as it is in the name of the world as it ought to be.

2. Service solidarity. Building upon lifestyle solidarity (“downward mobility”) is solidarity in the context of cooperative action. The TUL555 course is one of five practical training (field internship) courses, each operating through community organizations based in or serving the urban poor communities where students reside. Each student completes forty hours of voluntary service under the mentorship of seasoned entrepreneur-practitioners.

The real lives of poor people are often rendered invisible by mainstream institutions. To understand why particular groups of people have been relegated to the margins of global society, detached study is inadequate. Knowledge easily becomes “inert”—memorized from texts or lectures but not actually tested through firsthand experience. Deep learning requires that students enter into a critical awareness of actual conditions, causes, and consequences as community residents experience them. The service collaboration within local schools enables both community pain and possibility to be made evident.

3. Personal piety. The personal character and spirituality demonstrated by the servant-scholar is central to making theology relevant in the public realm (e.g. within schools). However, piety must be carefully distinguished from pietism. Pietism is sub-Christian and reactionary. It is fearful of “public” tensions, so seeks to escape into a “bubble” of the private. It withdraws from history and culture into a safe, black-and-white world of self-justifying rules and codes. It often becomes judgmental, harsh, pharisaical. Piety, on the other hand, seeks to practice the presence of God in the warp-and-woof of pluralistic urban life. Piety expresses itself in honesty, fairness, intellectual hunger, moral self-regulation, and compassion service. Piety celebrates life in all of its complexity and diversity, and seeks to find serenity in the midst of, rather than in escape from, the physical and social environment of the modern city. Flight into a private religious ghetto is not an option. Piety lives between church and society, doubt and faith, the “Fall” and redemption. Piety is the practice and the celebration of the presence of God in the midst of life, including educational life.

4. Cultural engagement. The MATUL program considers everyvocation—whether in for-profit business, civil service, public health, or community education—as a religious vocation. “Religious” to the extent that we make things or change things as God’s image bearers and in accordance with what we understand to be God's will in the world. invites cultural engagement. Through lifestyle and service solidarity, students become involved with the givens, the "materials," of city life in the developing world. They learn to engage urban culture with insight and understanding, with moral sensitivity and accountability, and with creative imagination and self-expression. Culture happens when a host family pools resources to pay rent; when a church surrounds a substance abusing congregant with love and acceptance; when a teacher explains a mathematical procedure.

During the school internship, MATUL students engage culture as they support teachers and parents in assisting young learners (the "slow" as well as "fast") in understanding literature and math and science and geography, as well as the "basic skills" that go along with them. Engaging these subjects is just as “religious” as a study of the Bible and church history. Not only do such subjects most directly and productively present the variety and complexity of human existence; they also directly and productively promote the major aims of “Christian” education, namely, growth in intellectual insight and understanding, growth in moral awareness and choosing, and growth in creative self-expression and action.

5. Cultural discernment and transformation. While the integration of faith requires doing culture, it also involves judging culture. We live and learn in a world of systems, institutions, and structures can do good and evil at the same time.

Every business corporation, school, denomination, bureaucracy, sports team—indeed, social reality in all its forms—is a combination of both visible and invisible, outer and inner, physical and spiritual. (Walter Wink)

These “powers” form a complex web that we can neither ignore or escape. One of the educational challenges for MATUL students, as well as for urban poor churches, is to learn how to discern the spirits of institutions and structures. If they are organized around idolatrous values and what Wink calls the "Domination System," they must be recalled to their divine vocation—the intellectual, moral, and creative well-being of persons.

Faithful cultural discernment can get derailed in two directions: cultural disengagement in favor of just “preaching the gospel of individual salvation” (the fundamentalist error) and cultural accommodation that ignores the discontinuities between the kingdom of God and modern urban life (the liberal error). Both diminish the power of the gospel. It is a gospel imperative, securely grounded in a faithful biblical hermeneutic, that the cross of Jesus Christ, the central point of all human history, is the key not just for personal salvation, but also for any understanding of faithful Christian living and gospel witness in every sphere of life. In fact, genuine sharing of the gospel requires godly cultural engagement in all those aspects of ordinary life. The Bible claims that that all things were made in and through Christ (Colossians 1); that God sustains the world moment by moment in all its capacities (Hebrews 1); and that we are called to “struggle” with culture (Eph. 6:12) by bringing every thought into subjection to Jesus Christ (2 Corinthians 10) and acting to shape culture Gen. 1; Matt 28; Rom. 12; Col. 1). We are to follow the example of Jesus who prayed that God’s “kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10).

The Bible is replete with examples of cultural discernment and action:

-

Joseph faithfully served God and the people of Egypt by instituting a food conservation program (Genesis 47).

-

Moses choose to identify with the Jews rather than with Pharaoh’s court (Exodus 2).

-

God instructed Jeremiah while in exile to seek the peace and prosperity of the city in which God’s people found themselves (Jeremiah 29).

-

Daniel and friends becoming qualified to function in the king’s palace in pagan Babylon (Daniel 1).

-

Jesus confronting the contemporary culture by communing with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well (John 4).

-

The persons of faith listed in Hebrews 11:34 “conquered kingdoms, administered justice, became powerful in battle and routed foreign armies.”

-

·Paul making himself familiar with the pagan Epicurean and Stoic philosophers of Greece so that he had an onramp into the public discussion in Athens to testify of Jesus and the resurrection at the Areopagus (Acts 17).

As MATUL scholars, we can accept with gladness the vast deposits of God's common grace in human history. The program invites us to “do the world's work” joyfully and productively together with unbelievers. But along the way, we will also take into account that dark line that runs through all of history. The divine story (the kingdom of God) carries both affirmation and negation. It uses internal languages (God, Creation, Christ, Spirit, Sin/Evil, Common Grace, Redemption, Reconciliation, Atonement, Judgment) to criticize a public culture driven by economic growth, resource exploitation, increased bureaucratization, privatization, moral decay, and state-sponsored violence. At the same time, the kingdom helps us to construct a positive agenda, as it discerns in public institutions signs of freedom, life and common grace that can be build upon. The task of public theology is ultimately to nurture, deepen, and transform the common life within which we exist.

In terms of slum-based schooling, both public and private, we might question the swing toward an authoritarian imposition of subject matter upon young persons in the name of "basic education” or “catechizing." We may find such bald subject-matter "conditioning" in violation of both human personality and good subject matter teaching fully as much as educational permissiveness does. A radical esteem for the humans created in the image of God may convince us that teaching be suited to the learner's way of learning, rate of learning, and developmental readiness for this or that concept or skill or inquiry. As image-bearers, young persons are “glorious ruins”: “glorious” with a profound need for compassionate encouragement, but also “ruined” with a profound need for compassionate correction. Such a view of persons will inevitably shape what you observe during school visits, how you value some pedagogical practices over others, and, above all, the hope you sustain for human development in the midst of the broken urban systems.