Urban Leadership Foundation

A hub for leadership training in cities and among the world's 1.4 billion slum-dwellers

Help! Help! I'm Dying!

Viv Grigg (from Cry of the Urban Poor)

Reference: Grigg, V. (2005). Cry of the Urban Poor. GA, USA: Authentic Media in partnership with World Vision.

The gospel had a daughter—prosperity.

The daughter ate the mother.

— Anonymous.

POVERTY INVOKES A RESPONSE in the heart of God. Pastoral concern for new believers automatically leads the Christian worker into the complex and perplexing issues of how to resolve economic needs.

Bread for the poor, or bread plus the Bread of Life?

In this chapter I reaffirm my underlying thesis that the church is God’s primary agent for social change. As the kingdom enters a community, and afterwards, it brings about economic transformation in the lives of individuals, families and at times, of the community. The causes of squatter poverty are generated by the city. Here too, it is the church of the city that can bring transformation, for the spirit of the city can be transformed by the church.

In Asia, the response to the poor has been inadequate. Churches have given bread to the poor but have kept back from them the Bread of Life. Partially, this is because governments want economic help from Westerners and are happy to allow the entrance of aid programs. They are not interested, however, in missionaries bringing religions that are foreign. Partly it is because of a lack of understanding of the scriptural patterns of incarnational mission on the part of the Western agency—a lack of understanding about the centrality of the church in effecting social change and how the kingdom grows.

Donald McGavran considered this aspect quite extensively in his major work, Understanding Church Growth.1 His work on the issue of serving the poor is outstanding, indicating both a deep social conscience and a brilliant ability to understand the practical issues of poverty. His primary thesis has become known as “Redemption and Lift.” I have talked with many affluent pastors who have misused this phrase as a justification for not going among the poor or to derogate church planting and aid among the poor.

Traditional responses

Generally the Western evangelical church has responded to poverty by directly using the gift of mercy to meet perceived economic needs of the destitute. This has been channeled by Western aid organizations either as aid for orphans and those struck by natural disasters, or into an integrated community approach known as community development.

This term has developed from a perspective that considers the poverty of the slums to be primarily a micro-economic issue. It tends to focus on economic projects as a means for the economic uplift of families in a community. Occasionally such projects encompass the whole community, in multiple facets. Occasionally they are seen as potential models for wider macro-economic policies.

Community organization

Marxists and more radical social workers have preferred an approach that has come to be known as community organization. This perspective has been popularized in Saul Alinsky’s models and is common in the Third World, where poverty is seen more as the result of oppression and class dominance or class struggle.2

Community organization tends to focus on the process of helping leaders in a community to identify needs, evaluate potential solutions, gather resources and deal with issues of injustice confronting them. It perceives poverty primarily in political terms—in terms of power and in a context of class conflict. There are Christian community organization approaches that avoid some of the ethical failures of those based on Marxist world-views, but take seriously the conflicts and confrontations between various groups in society, often rich versus poor.

As Bob Linthicum formerly of World Vision’s Urban Advance points out, community organization is particularly adapted to the city, with its concentrations of political and economic power and of poor and powerless. Community organization tends to be action-oriented and confrontative, as opposed to program or process-oriented community development.

We walked into a slum of 560 houses that lined a concrete path. Then we sat and talked with two 20-year-old men.

“In three months we will be forced off the land,” one said. “Already several times they have tried to burn us out.”

“Do you have any committee of squatter representatives?” I asked.

“No, everyone does his own thing. Nobody cares for others. If you are rich enough you can move out. If you are poor, there are no plans for you. We have no place to

go.” The hopelessness of the poor was written on his angry face.

I told them stories of urban poor in other countries—of their battles for land rights, and of their successes.

“You are the first one who has come and talked to us like this. Why do you care?” they asked.

“Because one day I met a king who loved justice and righteousness, and I loved that king . . .”

I told them how the coming king would set up a just government—one where there would be no more poor, no rich. One of them talked of his record as a thief. I told him of the thief on the cross, and of converted murderers I had come to know and love.

I wanted to stay. I felt sure that a way could be negotiated by bold leadership and prayer to a God who delivered a slave nation.

Evangelism and discipleship in the slum community must involve a servant who will do justice. And that justice will necessarily involve mobilizing the poor to negotiate with authorities. Knowing how to obtain rights is a skill that can be learned. It is a necessary component of a slum worker’s equipment. To fail in the political arena is to lose the right to minister to the leadership of the community.

Evangelism is not contradictory to doing justice. It flows easily in a context of working with people at their point of need—the point at which they are being violated. “For I, the Lord love justice; I hate robbery and violence” (Isaiah 61:8).

No easy solutions

The solutions to poverty are not as simple in practice as either of these theoretical approaches or variations allow. The first issue that has to be addressed is an understanding of the nature of the type of poverty itself (its effects). This quickly engenders other questions of cause (see chapter five). We must discover the point of attack where we can best deal with the problem or cause, and the level of society at which action is both feasible and appropriate.

Typical Christian responses of aid and community development, even when done brilliantly, affect only the micro-environment of the squatter area. This is good when related to our commitment to the church among the poor as the central agent of change in the slums. It is inadequate, however, when we consider that the economics of the city have far more effect on squatter poverty.

The primary response of middle-class Christians (while not neglecting other issues) will probably be in the transformation of economic life, political life, government bureaucracy, and other structures of the city that perpetuate slum poverty. It will probably also be necessary to deal with international factors that increasingly loom as dominant forces in worldwide urban poverty.

Three movements to impact squatter poverty

I have spoken of three spiritual movements important in changing squatter poverty. They are necessary to deliver the poor. Without them the poor will not be uplifted. But we should not fool ourselves—they are not sufficient to bring about all the change needed. Only a returning king can accomplish this.

1.

Movements of churches among the poor

may transform the micro-economic and local political environment. This may be

done at the grassroots level in cooperatives,

vocational training, small business projects, and organized pressure for land

rights.

2.

Middle-class professionals,

practicing a holistic discipleship and possessing an intimate knowledge of the

poor, may effect change in the implementation and

governing of the cities at an urban planning level They

may be able to assist in matters such as self-help housing, provision of poor

people’s banking facilities, acting as middlemen to the institutions, combating

corruption and initiating medium-sized employment, etc.

3.

Christians in the international

elite may change the macro-economic systems of international debt, unjust trade,

and increasing monopolization by unaccountable

multinational corporations.

How the poor escape poverty

It would seem appropriate to explore what natural solutions the poor have found for moving out of poverty. The first observation of interest is that rarely in history have the poor themselves transformed the social system that causes their poverty. This is not their role. They are too busy exploiting every opportunity for survival. Even in revolutions, where the educated elite have been able to use the poor for their own ends, the poor still end up poor. In fact, they often are poorer than before, because of the dislocation of the economic, political and social structure they have caused.

1. Mutual aid associations

One poor people’s solution to poverty is found in the various forms of mutual aid associations. An example of these is a group of street vendors who daily give a small sum Into the collective pot, which is given to one trader for that day as a major capital investment in supplementing capital costs of stock. This suggests the possibility of similar cooperative styles of operating within the church fellowship.

2. Eliminating the middleman

As discussed in chapter three, loans among the poor are “flexi-loans” that benefit both the borrower and the lender. The time period and rate of the loans are frequently renegotiated. These loans are often in goods. They often are exploitative.

In establishing the church, one of the first things to do is to free the poor from moneylenders. It is also possible to cut out the middleman from rural areas or the distributor in the city. This way, profits in the businesses of the poor can grow. Again, a credit cooperative is potentially the most viable vehicle.

3. Migration

Historically, the primary means of escaping poverty has been migration. The primary economic uplift in Manila’s slums takes place through the export of people to the Middle East as laborers, or to Hong Kong as housemaids, where they earn dollars. The money is sent back to families in Manila’s slums each month so that houses can be built.

John Kenneth Galbraith, in a little monograph on Mass Poverty, demonstrates how this both uplifts the poor in the poorer areas and assists the countries to which they migrate.4 This is a solution based on the realization that the city’s macro-economics is a determinative factor, as far as poverty is concerned, far beyond what any micro-solutions can solve.

The Christian response would perhaps be the development of just employment bureaus for overseas workers. Existing agencies are often exploitive. It is not unusual for a Filipino, for example, to spend hundreds of dollars on papers to obtain visas, job applications, and tickets, only to find the employment agency has pocketed the money. William Booth and other Christians in England clearly saw the employment bureau as one of their primary ways of uplifting the poor.

4. Education

In an urbanizing context, where bureaucracy continues to increase, the entrance level to that bureaucracy is a graduate degree. In cities where there is expanding industrialization, a degree guarantees an income ten times that of an unskilled worker. In a world economy increasingly controlled by information technology, a degree that gives entrance to computers may provide an escape from poverty. But in a decaying economy, where the bureaucracy has increased so that most of income is spent on salaries and nepotism squeezes out new entrants, a degree may not be an appropriate solution. In Calcutta, for example, hundreds of thousands of educated university graduates have no work.

The normal practice in a poor family is to choose one member— usually an older son—and sacrifice everything to get that member through the educative process. He then provides for the next brother or sister.

The church may have a significant input in this process. This is one area where gifts from rich, foreign churches are positive and non-destructive to the indigeneity of the emerging congregation. The church may also have a significant input in education programs that supplement existing government schooling, enabling the youth of the church to progress to tertiary levels.

Expanding areas of the economy are natural places to seek training, such as computing, engineering and other technical areas. Scholarships should be given on an understanding of being repaid once the person is employed. Sometimes the donor of the scholarship becomes the person’s first employer. The repayment can then be used to support another worthy candidate through the same process. This is part of the understood culture of the emerging Third World city.

Middle-class solutions to poverty

The individual cannot usually break out of this vicious cycle. Neither can the group, for it lacks social energy and political strength to turn its misery into cause. Only the larger society with its help and resources can really make it possible for these people to help themselves.5

1. Poor people’s banks

One solution that has been looked at in numerous contexts is that of a bank of the poor. One of the primary objectives of the nationalization of fourteen major commercial banks in India in 1969 was to ensure that the requirements of the weaker sections of society would be adequately met. In keeping with this objective, nationalized banks have been progressively stepping up the flow of credit to priority sectors such as agriculture, small-scale industries, small borrowers and other weaker sections. The aim was to direct to this sector 40 percent of the total lending by March 1985. Thus, money has been available to the poor sector but its recovery and utilization has been poor.

P.K. Banerjee gives a strong analysis of an integrated program developed by the Calcutta Metropolitan Development Corporation with the nationalized banks. It succeeded in getting loans to the poor in only 33 percent of the targeted industries and provided only 12 percent of the targeted coverage. There were some significant reasons for the failures:

a. Non-deviation from principles of traditional banking;

b. An old obsession for security-tied advances;

c. Bank insistence on furnished guarantees;

d. Non-deviation from individual-approach lending to area-approach lending; and

e. Lack of branches with independent wings for retail banking.6

Banerjee discusses a new scheme for retail banking tailored solely to extending financial assistance to the weaker sections of society, with the idea of dispensing with the security and guarantee aspects of the bank loan. Under the scheme, credit is to be considered on the basis of the skill, expertise and know-how of the borrower. Both disbursement and collections are to be made at the borrower’s doorsteps, eliminating the loss of precious time of the small clients at the bank doors again and again. The success of such a scheme depends solely on direct contact and mutual understanding.7

The Christian basis for such a model is evident. The practical problems involved would be lessened by its development within the fellowship of the church. Interference from political personnel can be avoided, and corruption lessened.

2. Businesses to lift the poor from poverty

How does one uplift the leadership of a slum church to a level of economic security? We are dealing with a twenty-four hour subsistence economy, without the managerial skills of a money economy. The crucial idea to communicate is that money makes money the more it is used. The poor understand this with their personal money but funds held collectively are often slow in their movement because of traditional decision-making patterns.

We are also dealing with patterns of management skill that are different from that which is known in the city. Why don’t people keep records? The poor have a deep aversion to this. To start with they never have sufficient paper. It is used today for records. Tomorrow it is used for other purposes. If the past has been catastrophic and uncontrollable, why record it? Keeping records is not a logical step towards controlling the future. Living on a subsistence wage, one cannot plan beyond 24 hours. It is illogical to do so anyway, for any money saved will quickly be eaten up by relatives in need or by debt collectors from the past.

We must thus consider two patterns of learning: the nature of learning in a peasant society and the nature of learning in modern society. Peasant society has an amazing characteristic of everybody knowing what everybody else is doing at all times. It is also imitative. Each group is also aware of what similar neighboring groups are doing. Filipinos call it gaya-gaya, or the habit of copying what others are doing out of a sense of always wanting to be the same as others. New ideas seem to take off when people in a number of related groups begin something similar and the word spreads.

3. Cooperatives

From the analysis above, the church’s basic response to breaking the poverty cycle in the slums is the development of new mechanisms at the border between the upper and lower circuit economies. Among the most effective patterns of economic uplift of the poor, cooperatives of various kinds are significant options for several reasons, both practical and theological. They also are notorious for failure through corruption.

Cooperatives reinforce a number of kingdom values. Sole proprieter businesses may also reflect kingdom values but there are less pressures on the owners to move in the direction of the kingdom and more pressures on them to reflect the values of the world—particularly greed. Cooperatives are at times a logical step for a church that has a common fund for the poor. They require a mutual accountability, which strengthens personal ethics and a sense of social responsibility.

Kagawa8 of Japan developed the theology and theory of cooperatives extensively two generations ago by building on Raushenbush’s works and the Rochdale principles.9

In considering a cooperative for a slum church, however, many factors must be taken into account. Cooperatives are not generally successful in a situation of mobility. In other words, the slum would need to have some long-term stability (which is also a necessary condition for the effective development of a slum church). In general, cooperatives also require an extended family context—they are more suited to the group dynamics of peasant cultures. They are not so effective in a buoyant context where there is little poverty.

Bad management of cooperatives is notorious. The management of a cooperative is generally less accountable than that of a company since the boards tend to be more ignorant of management and business skills.

Credit cooperatives or revolving loan schemes provide credit those who want to produce but have no capital and otherwise would have to borrow money at exorbitant rates. Credit in small quantities and at a reasonable cost will satisfy needs that private banks cannot fulfill. If set up with strong participation of the people, there is strong social pressure to repay loans. Gratitude for being given a loan without the usual red tape or collateral is also an important factor in the success of such schemes.

But good management is needed, including clear bookkeeping. There is a thin line between consumer purposes and income-generation purposes. Sometimes a loan has to enable the poor person to survive so that he or she can work for income. Often repayments have to be rescheduled to be more realistic and to fit the family’s circumstances.

4. Political confrontation

It is unusual for the poor to rise up in a coordinated manner against those who oppress them. Such confrontation requires organization, planning, strategy and a middle-class or upper-class mindset. Catholic base communities in Latin America have enabled the poor to understand their situation and the structures of society (concientizacion—awareness building), and to use effectively their strength of numbers against the power of those who oppress. It is trained middle-class leadership that enables such confrontations.

Many times this is a viable and perhaps necessary option for evangelical churches. However, I have not found any effective models where such political action and church-planting have been integrated.

William Cook, who has studied these base communities in depth, comments:

The basic difference is that (they) begin as seeds sown in a larger community structure (natural communities) and slowly develop into a church, defined as the presence of the Word and sacrament. Meanwhile nominal Christians are treated as equals and not as second-class citizens or “unregenerate.” In Protestant church-planting we call people out from sinful social structures into a body of believers which is defined not only by the Word and sacraments, but more importantly by discipline. This last point makes all the difference in the world, I suspect. . . . Nonetheless, I am not totally convinced that Protestant base communities are impossible, because they are happening spontaneously in Central America in a situation of tremendous violence as a defense against institutionalized violence and brutality . . .10

At times, the process of breaking the forces that create poverty calls for a Christian political response, using the power of the masses. It is difficult, however, to integrate this political response with the task of establishing new churches, since establishing churches requires broad support from a total community. The gospel does not always generate such a positive attitude from all within a community.

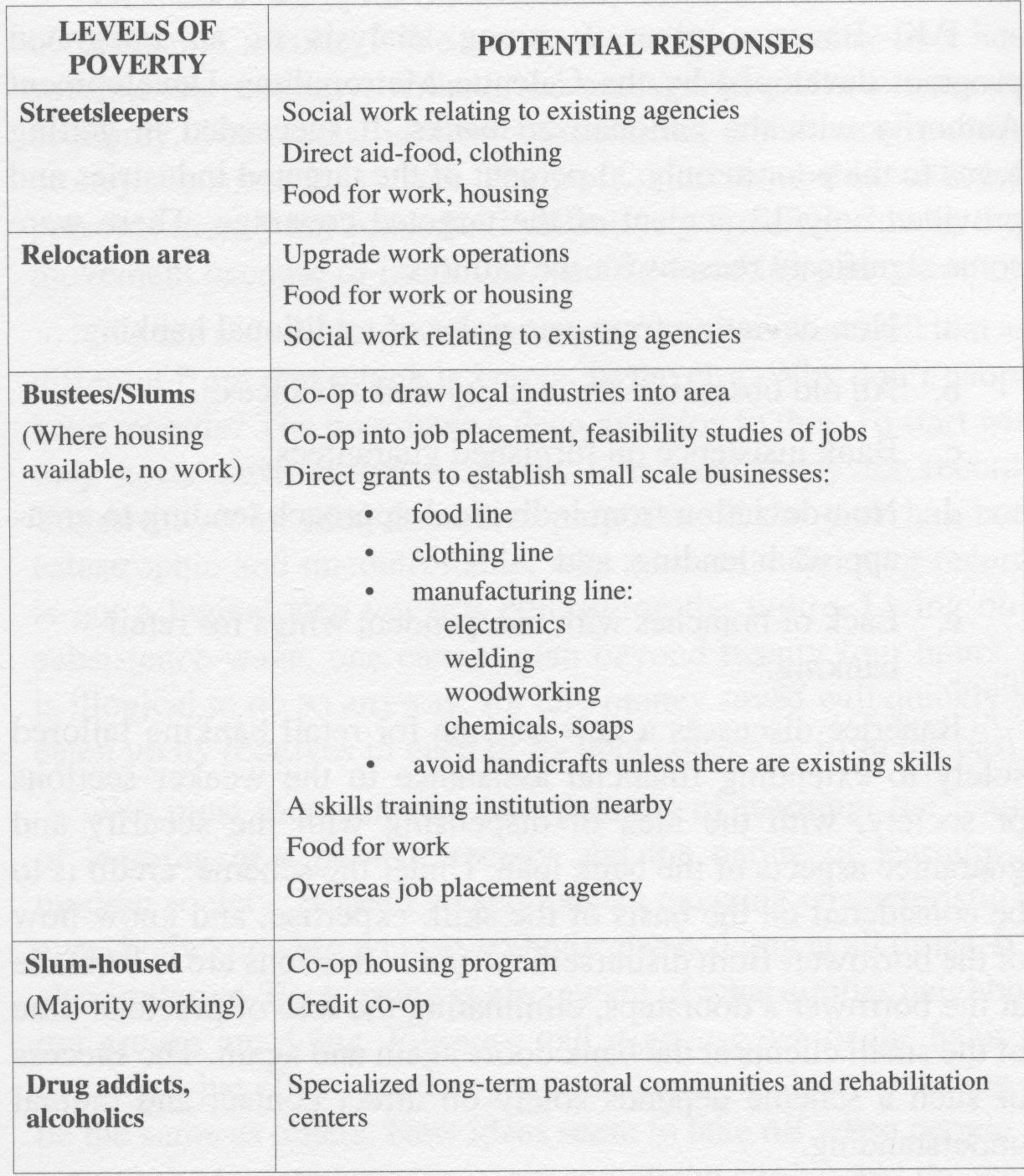

There are many other responses to poverty. Each kind of poverty requires a God-response. Each cause and each result require a different response. There is room for thousands of Christian organizations ministering to different groups of the poor.

Philosophical issues in development

We are focusing on poor people’s churches as the center of economic uplift. We observe, also, that the financial base of middle-class churches helping the poor is generally at a level of assisting families or communities. Since there is a historical pattern of involvement of evangelicals in projects. at this level of capital, it is good for us to examine some key principles that have emerged over the last decades.

1. Personalized, not programmed

What is it that has caused the renown of Mother Teresa? It is how God has used her prophetically to declare to the world the character of Christ. She has demonstrated the caring, personalized and incarnational nature of her Lord as he dealt with the multitudes. The poor of Calcutta do not talk much of other aid programs. They talk of Mother Theresa and her caring. The dignity of the poor is as important to them as the reality of their economics.

2. Incarnation—development from the center

By living among the poor there is a possibility that the outsider may develop an empathy and understanding of the issues faced by the poor. Success will be defined by the people, so it is wise that the worker seek definition of goals from the people at the center, not from office-bound executives.

Incarnation also leads to an understanding that the people have limited, simple and realistic goals. Not for them is the fancy mansion, but instead a plot of land with the title in their hand, and then after a few years and careful skimping of finances, adding a few bricks every week, the building of a permanent home . . .

3. Priorities the poor perceive

There is a natural progression of development in any city. There is also a general pattern of perceived needs in the squatter areas throughout the city.

“First a foothold, then a job.” Jobs are almost always the top priority in the people’s minds. They take precedence over the need for housing or water. But if jobs are available, water and electricity are generally the next pressing needs, preceding such things as sewerage or roads. So we may go on and for each community, developing priorities 1,2,3,4 . . .

The people’s priorities are critical in the process of development—not the priorities of the outside development worker who perceives their needs and seeks solutions.

4. Expected percentage of failure

Sixty-eight percent of small businesses in Sydney fail within five years. By contrast, 25 percent of aid programs in one study in Manila were successful, another 25 percent were partially successful, 25 percent were total failures. While there are factors that are not comparable, these figures indicate that, as a rule of thumb, the development worker must reckon on a degree of failure—failure that is just as real as that dealt with by any business owner. If development workers are not business oriented, they are well advised not to get involved in this area of ministry. There are ways of operating that will increase the rate of success and a great deal of available expertise in most cities.

5. Community involvement

To be effective, any group activity must be owned by the people involved in its implementation. They must feel it is theirs. This begins at the conception of the idea, the planning of its progress, and its implementation. Unless community leaders are involved in the decisions at the outset, the idea will eat up finances and produce little.

Many aid organizations enter communities, work with the people to define goals, and provide funding for specific projects and objectives. The difficulty is that the people are in process. They have no background for accomplishing these goals and hence need to frequently readjust through discussions. This often leads to a redirection of the goals, and frustration of the outside funding agency.

Once, a co-worker invested a large sum of money in a grand development project a friend had devised. The friend revised the plan when the realities made the original one unworkable. The friendship was broken, as the donor accused the worker among the poor of dishonesty.

Open-ended pilot projects are a wiser way to work with such communities. This enables the people to move a little distance in a certain direction, then rethink their priorities and goals in another without a continued sense of failure.

6. The multiplier effect

When faced with the enormity of the task of transforming poverty, why do we go on? With another billion squatters entering these cities over these next ten years, how is it we do not sink into a pall of discouragement?

The reason is because Jesus told us how a mustard seed multiplies and grows into a great tree. Spiritual life creates life. It has a dynamic to expand. The kingdom keeps growing, and even the gates of hell will not stop it. The small things we do today we know will generate many other things.

Similarly, in the natural sphere, life multiplies. From this comes wealth. When men with wisdom and gifts in practical matters handle money, it increases. (When people with eldership gifts handle money, it may or may not increase).

Projects begun with the poor, if they succeed, soon are copied. Even when our resources are limited, by faith we perceive a God who will multiply all we do. When blocked by corruption, oppression, envy or human error, we have hope in an infinitely interested God. He likes his people to succeed.

Yet we are not unrealistic optimists. Our optimism is based on a great pessimism regarding human nature and the nature of the principalities and powers that increasingly sap the life of the world’s poor. We know the script in the Scriptures, the prophecies of increasing oppression, and increasing authoritarian controls. We see a world increasingly groaning in pain, and know that Jesus must come soon—for he alone is able to save. Meanwhile we save all we can of the earth, her societies, and her people.

Patterns in the development of a diaconal team

Building on these principles, patterns can be developed. Bob Moffitt of HARVEST has developed an approach to use with existing churches in the slums of Central America. I will inadequately summarize this process, developed to a highly programmed level, for helping these small, isolationist churches to begin to relate to the issues of their community and as a result, begin again to let the gospel have an impact.

Begin by preaching the holism of the kingdom and show biblically how it affects all aspects of life. Then draw together the leaders of the church. From these a committee will be elected.

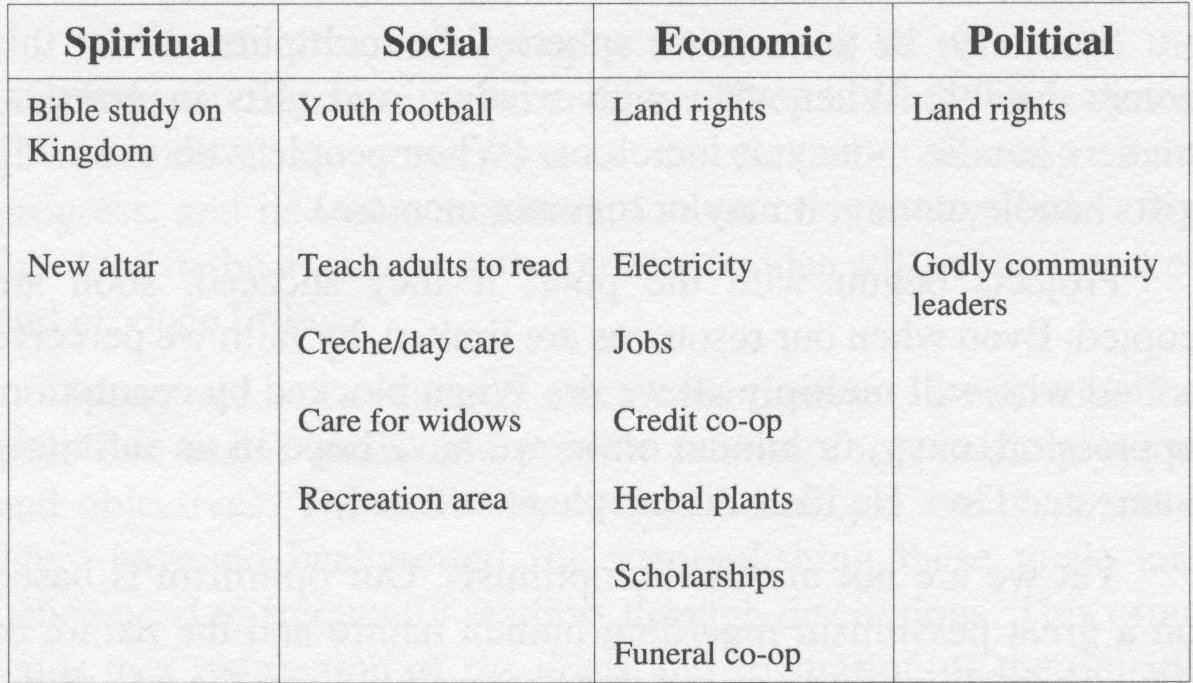

Get a blackboard, divide it into four parts, and dream with the people as to perceived needs in the community. A typical afternoon of discussions might cover the following:

Prioritize these with the people, both in terms of need and in terms of the relative ease of accomplishing something. Then work with them to make plans for one of each of these areas.

For the highest priority needs, plan field trips, contact government authorities for information on their programs, contact NGOs (non-governmental organizations), make a plan, and work with other community leaders outside the church, possibly drawing them into this committee.

We may extend this community development approach into community organization with its goal beyond mere projects. Defined in a Christian sense, the goal becomes enabling the people to understand fully their ability under God to effect change in the face of opposition from those who oppress them and deny their rights to basic human dignities.

In all community organization, it is important to start with realizable projects. Build the people’s sense of ability to deal with those in authority through small and positive experiences. Lay a base for political action slowly. When negative experiences occur, work through issues that arise with them.

Marxists and those who choose a confrontational approach often will use these occasions to increase bitterness between the classes. Christians, during these times, will seek to train people in biblical responses to oppression. Thus, when negotiations break down, develop manageable confrontational techniques that defuse violence but effect change. Before they break down, make sure a thorough theology of dependence on the sovereignty of God in the midst of suffering has been internalized by the believers.

Roles of missionaries, elders, deacons

The key actors in the growth of the church need to have a clear understanding of their roles. The missionary is a catalyst, a change agent who has a significant role in introducing a theology, new ideas, networking both inside the community and with outside resources, and generating some degree of group dynamic. But he or she is a guest and an outsider.

The missionary will only be effective if some insiders take these ideas to themselves. Insiders must be the developers and implementers.

For years, I have taught that it is wise for the missionary not to enter a community with great sources of funding. For years, workers because of their zeal for the poor, have violated this teaching, only to realize later that the people perceive them as a source of finance. This has greatly hindered the processes of evangelism and development. Jesus taught his disciples to go from town to town preaching, dependent on the people. While we need to take sufficient provisions for ourselves, because we are less mobile and more foreign than those first apostles, we need to go with a level of income that results in some degree of dependence on the people.

During the first year of church-planting, as a nucleus forms, we will not be administering great amounts of money for aid programs. We may use seed money on a more personalized basis with individuals. During this time, any use of money needs to be discussed with key advisers from within the community. It means that often there will be emergencies during which we can help, and at other times we will have to get on our knees with the people and pray for the finances with them so that they too learn to look to God and see him provide.

We need to do enough in this economic area so that the new believers see that God Is vitally involved in economics and can discuss the biblical teachings on economic issues. We teach by life and word.

But we wait, until gradually among the new believers, it becomes evident that some are gifted in the economic areas, some in management, some in servanthood, and some in business. These need to be drawn together into an emerging diaconate.

Over a period of time, by experimenting with meeting various areas of need, these emerging leaders will learn how to lead the church to a point where each leader, and ideally each member, becomes economically self-sufficient. The exception will be some widows and orphans who will always have some dependency on the church.

Deacons are not the elders. Nor are they the pastor, although initially the deacon has to exercise strong oversight in the use of funds. Elders have very clear ministry gifts. Deacons have very clear economic gifts. Because the process of discerning these gifts takes time, it is advisable not to formalize these roles too quickly, but have a series of ad hoc committees form for different activities or projects.

An emerging diaconate

In the following report a middle-class team was involved in founding a church. They are now transferring their vision to a group of emerging disciples who, in turn, are initiating a cooperative loan fund.

Over the previous year the economic committee had consisted of Pastor Jun and Milleth, Jun II and Thelma (all from the middle class Kamuning Christian Fellowship). At the time of the following report a new committee of local believers is being formed.

Report on Tatalon Economic Projects 1983-84

Adel Payawan (now a professor) has continued the herbal plants project which she began here, at Central Luzon State University. Belle Celedonio has now copyrighted her Christmas card production and has become self-supporting in it to some extent. She has been unable to delegate it yet but has made simple designs and patterns for non-artists to help her. She has borrowed 300 pesos to implement this. Pastor Jun’s vermiculture was a resounding success till the market disappeared.

Excess goods from last year’s shipment of goods from Hillsborough Baptist Church in New Zealand were sold to provide initial funds for the loan fund. Twenty people have taken out loans of up to 300 pesos at a time for projects such as meat stalls in the market, sari-sari stores; transportation and costs for job applications; paint brushes; a pancake stall; buying a harvest of vegetables and selling it; and buying a motorbike. These believers are being encouraged to develop a more structured credit coop where gradually the collective capital will increase. The total turnover of a capital of 1500 pesos has been 9471 pesos during the year.

Over 2200 pesos have been given away in acts of mercy for victims of stabbings, for medicines, to destitute widows, for a desperately ill woman. Over the last month, another 1500 pesos have been given for such needs.

Three university /technical courses have been sponsored from the scholarship fund, two in computing, and one in electronics. Repayment will be sometime after obtaining a job. The work promised in computing by the University of Life did not eventuate.

The total ministry income from local sources has been 10,324.66 pesos over the last year. This excludes the pastor’s support Good accounts are now available and an accounting system is now operational

Discussions with the Ministry of Social Services and Development are underway to pass long-term poverty cases onto them. A foster care program proposal has also been initiated. Melly is working on this.

Dressmaking is the next major project A group of interested people are being formed together. Melly and Jonel are working on gathering the necessary data. Nine sewing machines came with the gifts from New Zealand.

The remnant of the vermiculture capital will be spent on chicken-raising. It is a viable project, returning 400 pesos on 1500 pesos after two months with a high initial risk.

Notes

1. McGavran, Donald, Understanding Church Growth, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1980

2. Alinsky, Saul, Reveille for Radicals, New York: Vintage Books, 1969.

3. Linthicum, Robert, Empowering the Poor: Community organizing among the city’s ‘rag, tag and bobtail’, Monrovia, California: MARC, World Vision International, 1991.

4. Galbraith, John Kenneth, Mass Poverty, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2001.

5. Harrington, Michael, The Other America: Poverty in the United States, Penguin, 1965.

6. Chowdhuri, B., “Bank Finance for Slum Dwellers in Calcutta Metropolitan District,” Calcutta Slums, Calcutta: CASA, 1983, pp 130-132.

7. Ibid.

8. Kagawa, Toyohiko, Brotherhood Economics,

New York and London: Harper and Brothers, 1936. Excerpts summarized, NASCO, P.

O. Box 7293, Ann Arbor, MI

48107.

9. A group of weavers in 1844 in Rochdale developed some basic principles for cooperatives.

10. Cook, William, The Expectation of the Poor: a Protestant Missiological Study of the Catholic “Communidades de Base” in Brazil, Ph.D. Dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, 1982

© Viv Grigg & Urban Leadership Foundationand other materials © by various contributors & Urban Leadership Foundation, for The Encarnacao Training Commission. Last modified: July 2010Previous Page |