Urban Leadership Foundation

A hub for leadership training in cities and among the world's 1.4 billion slum-dwellers

God’s Happy Poor

THE POOR IN THE SCRIPTURE

Reference: Grigg, V. (2004). Companion to the Poor. GA, USA: Authentic Media in partnership with World Vision.

Questions continually rolled around my mind: “Why are the poor, poor?” “Why are they blessed?” “Which poor are blessed?” “Why does James call them rich in faith?” “Who are the poor Jesus spoke of?”

To understand what Jesus wanted us to do for the poor, I sat down with a friend one day and copied out every verse in the Bible about the poor onto small, white cards. I carried them with me for four years. They were my meditation day and night. They determined every major decision.

My concordance to the Bible listed 245 references to “the poor,” “poverty,” or “lack” in the English scriptures. They made an interesting study. There were five main root words:1

Ebyon: needy and dependent (61 times)

Dal: the frail poor, the weak (57 times)

Rush: the impoverished through dispossession (31 times)

Chaser: to suffer lack of bread and water, to hunger (36 times]

Ani: poverty caused by affliction and oppression (80 times)

The word Jesus uses in the New Testament for “poor.” ptochos, is the translation of the word anaw, which in turn is derived from ani.2 Anaw at times means “the humble,” but elsewhere, as in Isaiah 61:1 from which Jesus quotes; it has the meaning of “the oppressed poor.”

The concept of poverty and the analysis of its causes and effects change as the history of God’s dealing with his people progresses. Before the monarchy of David and Solomon, in the Pentateuch and in Job, societies were built essentially around extended family or clan structures. Riches were the blessing of God; poverty was brought about by some misfortune or through judgment of personal sin. The poor man was to be helped from his poverty.

From the time of the monarchy, a center of privileged people began to develop. Excavations in Tirzeh indicate that before the monarchy all houses had similar dimensions and furnishings. During the 8th century B.C. however, different districts had come into being: a well-to-do neighborhood for the rich; slums for the poor.

The rich began to treat the poor as though they belonged to a lower order. Poverty came to be seen as a much deeper deficiency in a person, particularly in the Wisdom literature (the Book of Proverbs and so on).

The poor, for their part, began to see their poverty as synonymous with being oppressed. The standard expression, “who oppresses the poor.” attributes the cause of poverty to the rich.

Hence, we find the prophets denouncing constantly the rich (called the oppressor or the unrighteous) and upholding the “godly poor.”

These are the ani, the oppressed poor with whom Jesus identified—”the poor of Yahweh.” “Poor in spirit” is an expression primarily describing this social class and its response to such oppression.

God’s plan for ministry

Suddenly, in the midst of these

new revelations about the poor, my plans seemed to crumble in front of my eyes.

After years of work, building relationships, molding ideas, and building

together, the leadership of the mission I worked under went through a time of

turmoil, related to this need to

“preach

the gospel to the poor.”

I returned to New Zealand

But God was faithful. The

relationships I had built with Filipino Christians opened the door back into

Manila and to

a ministry with the poor. Because of their commitment

to the poor, some of my Filipino friends had established an Indigenous

discipling movement called REACH. I began my work in Manila again, this time under

their auspices, determined to avoid being trapped into a middle-class

missionary lifestyle. This time, I wanted to dwell among the poor. I wanted to

enter into the knowledge of God. I wanted to learn to die to self, to security,

to my own culture, to my wealth.

The first step was to learn the language and culture of the poor. I boarded a crowded bus for a small city in a Tagalog province. Here I was to study the language of Manila’s poor, Tagalog, in one of its purest provincial forms.

I prayed: “Lord. I have no home here, no contacts, but I’m sure you’ll provide. Find me the poorest families. Since I’m unused to living among the poor, let it be a well-built home, with a good toilet so I can maintain my health.”

The historic Catholic cathedral in the town of 100,000 was full of images of saints, and there was only one Protestant church. I walked to the pastor’s house and asked for accommodation for a few days. Although he was gracious, I could see that he could ill afford to provide for me. I had known this man when he had been a fine preacher in a city church. He had chosen to minister to the rural poor at no little cost.

After two days with the pastor, the pastor’s assistant came to take me to his home. We traveled by tricycle (a motorbike with a highly decorated and stylized sidecar costing about five cents a ride) along the half-formed muddy tracks into the unfinished government subdivision. The local wisdom was that corrupt government officials had embezzled the development funds through various means. As we rode along the track, I drew shy smiles and calls of “Hey Joe!”

When we arrived at the house, I thanked the Lord. It was perfect.

Ka Emilio, the father (sixty-eight years of age), told how the family had constructed the house in one week at a cost of $130. It was all I’d prayed for: concrete walls and a tin roof (or a “G.I. sheet,” as Filipinos call it). The toilet had a concrete floor, with enough room to “shower” by scooping water with a tin can from a plastic bucket. An old frog and some neighborly lizards shared it with us. Next to my bedroom was the community pump.

We put in a bunk above my friend’s bed. We had to push the wall out six inches since I was ill suited to a Filipino-sized bed. This gave us a five-by-six foot bedroom to share.

Ka Emilio was a man of old Tagalog dignity, a gracious and hospitable host. He coughed constantly, with one lung rotted by tuberculosis. He maintained his health by planting and watering vegetables and the trees around his home.

I knew no Tagalog and he knew no English, but we had many long conversations. Once he described the Japanese invasion of their city, complete with dive-bombing and its effects on the frightened people, all in dramatized Tagalog.

He taught me much of the dignity and pride of the Tagalog people whom I had come to serve. While living in Ka Emilio’s house, I saw the Biblical concepts of poverty take flesh in the community around me.

The poor who lack

I ate next door at his daughter and son-in-law’s home, but I would watch Ka Emilio cooking his rice. At times, all he had to eat with his rice were the leaves off the trees he’d planted.

Job 30:3–4 tells us of such poor:

Through want and hard hunger they gnaw the dry and desolate ground; they pick mallow and the leaves of bushes and to warm themselves the roots of broom . . .

Ka Emilio was one of the chaser: those who lack the basic necessities of life, those who want.

At nights, I would lie sweating on my plywood bed and search for answers. “Why was he poor?” “How could such a poor man be blessed?” A study of the word chaser told me some causes of this kind of poverty.

Proverbs tells us that wickedness causes the belly to suffer want (13:25); too much sleep and want will attack us like an armed robber (6:10,11); hasty planning leads to want (21:5); oppressing the poor to increase our own wealth, giving to the rich, (22:16); loving pleasure (21:17); or miserliness and gambling (28:22) all bring us to want. This poverty is caused by personal sins.

The Scriptures also speak of the solution: “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want” (Psalm 23:1). “Those who seek the Lord lack no good thing” (Psalm 34:10).

One day through an evangelistic crusade, Ka Emilio came to believe that Christ had died for him. I gave him a Tagalog Bible in comic form [the poor read comics, not books). Perhaps time would lead him to a complete obedience to this Lord who is Shepherd, and this would lead him and his family out of want.

Even then, I knew that such a solution was insufficient. Deeper causes to poverty than personal problems—communal and national and global problems—require biblical solutions at each appropriate level.

But I needed to begin at the level of the personal and spiritual and explore outward. We tried raising rabbits to supplement Ka Emilio’s income. When that failed. I bought him a goat, but he eventually sold it, as he was too old to constantly take it out to feed. Ultimately, the solution to Ka Emilio’s poverty was a son who got a job in Saudi Arabia and sent back American dollars.

Poverty and sin

Some poverty is caused by sin. But poverty also causes sin. The broken social structure of the squatter areas creates an environment, which exercises little social control over sin. Poverty causes people to steal.

Proverbs 30:8–9 offers this sound advice:

Give me neither poverty nor riches: feed me with the food that is needful for me, lest I be full and deny thee. And say, “Who is the Lord?” or lest I be poor and steal, and profane the name of my God.

A favorite meal in the Philippines is cooked dog meat and beer. One day I was walking round the comer of the track and came across three men quietly pushing a jeepney loaded with dogs. They had stolen them and would sell them to a restaurant for meat. That same week I passed a truck. People were draining it of gasoline.

![]()

![]() Ninety

percent proof

Ninety

percent proof

Poverty also causes drunkenness.

The first thing one notice among areas of poverty is drunken men. Everywhere

there are groups of men drinking—at all times from morning to night.

Drunkenness and alcoholism cause destitution, but most drunkenness among the

squatters is a result of the poverty in which the men find themselves.

Unemployment results in

drunkenness. Even Proverbs indicates this. When it advises against kings

becoming drunk, it suggests:

Give strong drink to him who is

perishing, and wine to those in bitter distress; let them drink and forget their

poverty, and remember their misery no more (Proverbs 31:6,7).

(We should not interpret this as a

license for the poor to drink, but rather as a plea for sober kings!)

One Filipino study of a slum

community indicated that 68% of the employable adults are unemployed.3

In Tatalon it was 42%.4 Drinking with friends is a way to fill up the

day and drown out the sorrow, despair, and lack of self–respect

inherent in unemployment.

Ka Emilio’s

two sons became my good companions. Living with them. I began to understand why

they were poor and why they were often drunk. Seraphim had been a soldier, but

lost his job and income for two years because of an injury. In my diary one

night, I jotted:

Tonight Seraphim will drink himself to sleep. It is hard to be without work. If he had work, he could get married. His girlfriend is already working and has graduated. He melancholically plays his guitar on the doorstep as the sunsets. A man of dignity, a soldier of honor seeking to maintain his dignity with the Beatles and a bottle. How do I help his soul and body? How can this poor man be blessed except in the kingdom?

What is the solution to drunkenness? Some years before I had traveled through a valley in Bukidnon. The homes were among the poorest I had seen—thatched huts, only a few meters square. I asked around to discover why. A local rice wine was ninety percent proof. Everybody drank it. Thirteen or fourteen year-old pregnant girls drank it. Children were born to drunken mothers and so grew up with the taste and desire for wine. People died before they were thirty. So, it went on for generation after generation.

Then an older lady missionary came in and started an orphanage. From this base, the good news spread. The preaching of the gospel broke that cycle. Chaser, those whose personal sins have caused poverty, are blessed by receiving God’s kingdom.

The poverty of immorality

Poverty provides an environment not only for drunkenness, but also for immorality. In the immediate cluster of houses around our home, very few couples were legally married. Many of the women had lived with two or three husbands. A number of men had a kabit (a second wife). In one survey we did informally, over 30% of the men indicated that they had become squatters as a result of some form of immorality—often in the process of “eloping” or taking a new wife and hence leaving their provincial home.

Squatter areas seem to be the ultimate collecting pot for the moral outcasts of society. Perhaps this is because they are areas where social norms and values have broken down almost totally, with Immorality and infidelity running unchecked and unashamed.

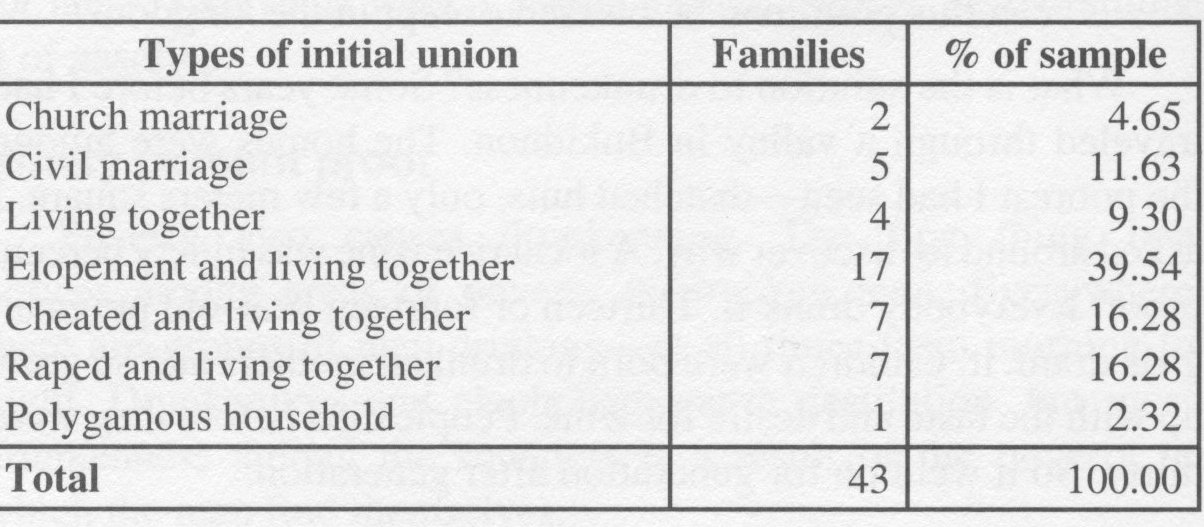

In a survey of the 43 neediest families in one slum area, only one-sixth of those interviewed had been legally married when first living with their wife..5 Six men and four women had been previously married. The figures are symbols of pain, anguish and frustration.

![]() Frustration

over broken relationships erupted one day when I was sitting in my upstairs

room, preparing a message in Tagalog. Suddenly, I heard an angry voice in the

rooms below:

“I’m

going to leave him! I’ll

file a law suit!”

Frustration

over broken relationships erupted one day when I was sitting in my upstairs

room, preparing a message in Tagalog. Suddenly, I heard an angry voice in the

rooms below:

“I’m

going to leave him! I’ll

file a law suit!”

Two or three neighboring relatives

rapidly materialized to quiet down their niece, each passing on a piece of

advice.

“The best thing is to stay with him,” one lady said. “I remember when I first heard that the Bombay (Manilan terminology for an Indian—her late husband had been one) had another woman. I was furious. So I followed his jeepney and watched. They met at a bookstand, so I went and talked nicely to her. I didn’t let her know I was his wife. She told me she had three children also. I have even had her children in my home when she could not cope!”

Her daughter added her own story: “I cried for months when the father of my son married her, but I’ve learned to forgive.”

But the woman in distress would not be quieted. What could she do? He had another woman! There were many discussions during the next few days as the women sat for hours at a time, analyzing what options were open when their common-law husbands moved on to the next woman. Would they remain faithful themselves? Should they find another, take revenge, or move out of the community?

Immorality creates poverty by generating bitterness, jealousy, insecurity, family disorganization, hatred, and murder. It is difficult for a man adequately to support more than one family. When relationships have been destroyed and broken, it is difficult for the children to learn how to relate to any form of authority, or develop the management skills necessary for many jobs.

Personal sins help create poverty. Poverty, in turn, provides an environment for personal sin. This kind of poverty is only transformed by a gospel and a discipleship that enables people to be freed from these sins.

The dependent poor

Of course, not all poverty is

related to personal sin. The words ebyon and dal describe another

kind of poor. Ebyon

is the designation of the person who finds himself

begging: the needy, the dependent.

Job indicates the appropriate

response to these ebyon when he describes his personal identification

with those in need:

“I

was eyes to the blind and feet to the lame. I was father to the poor (ebyon)

and I searched out the cause of him whom I did not know”

(Job 29:15–16).

Job’s

response was the only possible response we could give when we met a deaf and

dumb stowaway. We had parked a borrowed jeep downtown after transporting some

people back to Manila from a conference. It was late, but the crowds continued

hustling and bustling. A boy in ragged clothes indicated he would watch our

jeep for us and make sure that no one stole it. We nodded agreement, knowing

that for many boys this was their only income.

On returning, we gave him a

peso for his trouble. He signaled his thanks, but seemed strangely silent.

He went and sat down again in the shop doorway.

I got into the driver’s seat, but the compassion of Christ would not let me start the jeep.

“Do you think he’s deaf?” I asked my companion, a social worker.

She nodded. I sat and thought. How could I return home to my luxury and leave one in such destitution?

“Let’s go talk with him.” I said suddenly, leaping out of the jeep and squatting beside him. I tried speaking, but he just nodded his head. Fortunately, my companion had some training in sign language.

“I came from Cebu (a city on an island south of Manila),” the boy signed to us. “I stowed away on a boat. It travelled three days and three nights. I arrived in Manila with three pesos in my pocket.”

The signs were accompanied with fear and hope. My friend translated them into English.

“Why did you leave home?” I asked.

“Why did you leave home?” she signed.

He nodded and with great rapidity of hand action explained. “They always used to laugh at me. My father used to beat me because I was deaf.”

She translated. I nodded.

“Where

do you live?”

she signed.

His home was a six-by-three-foot packing case, slotted among the others by the river.

I knew about a restaurant in the

park that was staffed by people from a school for the deaf. We signed to him

that we would meet him the next day and take him there. Eventually, he began

attending a school for the deaf run by some fine Catholic laymen. Some years

later, I heard that he was successfully working as a chicken farmer.

This type of poverty is not caused

by sin; it is poverty caused by natural calamity. It is of these poor that Jesus

spoke when answering the query of John the Baptist (“Are

you he who is to come, or shall we look for another?”):

The blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, and the deaf

hear....”

(Matthew 11:3–4).

Jesus also describes them quoting Deuteronomy 15:11:

For the poor (ebyon) will never cease out of the land, therefore I command you. “You shall open wide your hand to your brother, to the needy (ebyon) and to the poor (ani) in the land.”

It is to these ebyon that God’s kingdom brings healing and socio-economic uplift.

Too frail to work

“Oy, Kumusta?” (How are you?) I asked. “How’s your job-hunting going?”

She smiled sadly and answered. “I can’t take a job.”

“Oh, why is that?” She had studied in the same class as Coring, who was typing for me at the plywood table of my kitchen-cum-office.

“I’m too weak. I cannot work five days a week, so I cannot take a job.” She looked away from my eyes, staring at the drawn-back sack that acted as a curtain.

I felt something of the sorrow God must feel for such people. Who would rescue these poor? Poverty is frailty and weakness. In Hebrew the root word is dal. This word is connected with the word dallah. the “class of the poor.”

The Old Testament (2 Kings 24:14) describes the poorest in the land who were left behind during the exile to Babylon.

Jeremiah (5:4) tells us that these poor ones were looked down upon, while Job (20:19) tells us that they are easily crushed and abandoned, without the means to recover from loss or calamity.

These dal are blessed in

the kingdom. In the song of Hannah we read:

“He

raises the frail poor (dal) from the dust. He lifts

the needy (ebyon) from the ash heap to make them sit with

princes and inherit a seat of honor”

(1 Samuel 2:8).

Husband of widows

Widows also fall into this category of those made poor by calamity.

Quietness stole softly over the slum, replacing the cacophony of the sound of a thousand people crowded into their plywood homes. The moon and the stars silhouetted the patchwork of old tires holding down the roofs from typhoons. It was midnight, the hour for quiet prayer.

My heart ached for the situation

of the widow next door. She had been kind to me. My thoughts and eyes sought out

the houses of other poor widows. I thought of the rice they’d

cooked that night for their children, some without fish, meat, or vegetables.

Suddenly. I realized,

“Lord,

if you are the father of orphans, surely that makes you the husband of widows!

They are especially yours!”

I began to pray for ways to help these women. They were poor through no sin of their own, nor even the sin of others. Their circumstances had simply happened. And so God takes responsibility for them: ‘The Lord watches over the sojourners. He upholds the widow and the fatherless” (Psalm 146:9). We, too, are to incarnate his love amongst these dallah.

Children of sweat

Children, too, are important to

Jesus. They also belong among the frail and the weak—the dallah. How can

one help but love children? As I walked down the back paths into the community,

I would hear cries of

“Kuya

Viv! Kuya Viv!”

(“Big

brother Viv!”).

Small children would laughingly greet me all the way, until I reached my own

house. Often we would play games together.

There is a Tagalog phrase,

“anak-pawis,”

which means

“child

of sweat”

or “child

of poverty.”

Ninety-two percent of children in the slums and 87% of the total population in

the Philippines suffer from intestinal parasites. Sixty-nine percent of Filipino

children under six years of age are in various stages of protein calorie

malnutrition. A further 45% of them have first-degree malnutrition, meaning they

are 10–24%

below their standard weight.

Indelibly lined in my mind is the

memory of a friend, holding in her arms a little child with swollen stomach,

spindly arms, swollen head. He was sick and retching constantly. She tried to

comfort him while telling me that when his father came home, she would get some

money for medicine. I knew he had no money to bring her. On the mat slept five

of her other eleven children.

John the Apostle said:

“If

anyone has the world’s

goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him. How does

God’s

love abide in him?”

(I John 3:17).

Poverty is dispossession

There is yet another cause of poverty beyond the realm of personal sin and the calamities of life. This is poverty caused by the sins of the rich, the leaders of a people, or the oppression of a conquering nation. Two Hebrew words are related to this: rush and ani.

Rush means “the dispossessed poor, the impoverished.” Such is the poverty of the tenant farmers forced off their lands to make way for the multinational sugar and banana plantations, or because of unfair land reform.

Proverbs 13:23 tells us: “The fallow ground of the poor yields much food, but it is swept away through injustice.” Many squatters come to Manila because their livelihoods have been swept away by injustice. This is essentially a passive phenomenon. It is the people being disinherited: first in the province, then in the city.

God looks for an intercessor who will seek justice for these poor: “But this is a people robbed and plundered . . . they have become a prey with none to rescue, a spoil with none to say ‘restore!’” (Isaiah 42:22).

White slavery

The dispossessed also include slaves. Aling Ada’s daughter was taken by a syndicate that enslaves girls in drugs and prostitution. These syndicates of “white slavery,” as it is called, jail girls in barred houses and force them into prostitution. After a few years, the girls are not only physically but also emotionally enslaved for life. Miraculously, Aling Ada’s daughter escaped a week after she was abducted.

People refer to darkest Africa, or General William Booth’s “In Darkest England.” The tourist belts in the Asian cities can rightly be called darkest Asia.

As slum statistics are unmentioned in the formal record books of Asian nations, so slavery is officially not spoken of. In the provinces, recruiters tempt girls with offers of good jobs in Manila. But upon reaching the city, they find themselves locked into these “safe houses” from which there is no escape. Once forced into the trade, the desire and ability to escape such a lifestyle goes. Few get out.6

Others are sold by employment agencies to men in the Middle East, Italy, Japan, Hong Kong and elsewhere, often under the guise of being waitresses or house girls.

Bangkok’s

population, for example, of 8.3 million includes a small army of 60.000 women,

mostly prostitutes, working out of 350 go-go bars. 130 massage parlors, and 100

dance halls.

Women who make the sex business

successful in Bangkok see few profits for themselves. Travel agents skin off

50% of the take, bars and brothels pocket most of the remainder, leaving

varying cuts from that share for the girls.

“We are down to our last resource,” says Karinina David, a professor of community development at the University of the Philippines. “Once you sell your women and debase your culture, there is not much left.”

Amos pronounces God’s judgment on a nation for the same sin:

Because they sell the righteous for silver and the needy for a pair of shoes, they that trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth and turn aside the way of the afflicted (Amos 2:6–7).

God looks for women of commitment who will give their lives to rescue these girls. Women who accept this ministry must try to effect changes in the law to break the horrendous sale of flesh that parades itself under the name of tourism. It is a dangerous task. Two friends who tried to combat it at a government level were threatened so often they gave up. Yet Proverbs 31:9 says to continue to “open your mouth, judge righteously, maintain the rights of the poor and needy.”

God looks for women who know that he will be their protector, as he was for Amy Carmichael and her band of women when they rescued temple prostitutes in India.

Who are the blessed poor?

The fifth Hebrew word used in the

Old Testament is ani and its derivative anaw which is the word

Jesus used when he talks of the blessed poor.

The root word means to bring low,

to afflict, to ravish, to violate or force. It is used for a whole range of

exercises in domination, such as when the people of Israel were afflicted by

their taskmasters in Egypt (Exodus 1:11–12).

It was used also to denote the response of humble dependence on God to such

oppression (Job 34:28; Psalms 34:6). The ani is one bowed down under

pressure, one occupying a lowly position, one who finds himself in a dependent

relationship. It means

“the

humble poor of Yahweh”

or “God’s

poor ones.”

People who are ani are not

contrasted with the rich, but with people of violence, oppressors who

“turn

aside justice from them”

(Amos 2:7), who rob the poor of their rights by making unjust laws and

publishing burdensome decrees (Isaiah 10:1–2).

Much of the poverty of Two-Thirds

World countries can be attributed to such causes. Several centuries of

iniquitous decrees by both the Spanish and the rich 400 families that rule the

Philippines have resulted in a society oppressed, afflicted, and impoverished.

These blessed poor, then, include

the needy (ebyon) and the frail (dal), the dispossessed (rush)

and those who lack (chaser). But within these categories, underlying

them is poverty caused by the ruthlessness of the powerful, who deny the rights

of the poor and do not respond to their calamities.

Is poverty blessed?

God rebels against poverty, for it destroys his whole creation. Nowhere in the Bible is poverty an ideal, as it became with later mystics. Nowhere is poverty glorified or romanticized. The fact that the poor are sometimes, and with increasing frequency in the scriptures, called righteous is not so much to their own credit. They are righteous because their oppressors are so terribly unrighteous. The poor are therefore righteous in comparison with the oppressor who withholds their rights.

Nor are the poor blessed because of their material lack or their economic class. This would ignore salvation by grace and imply that salvation is given according to economic and sociological status. Poverty is not blessed, but the poor are—those poor who become disciples. The Beatitudes were spoken to Christ’s disciples. They were truly “the poor of Yahweh.” Because of their poverty, they trusted in God in a spirit of dependence. Matthew 5:3 (“Blessed are the poor in spirit”) and Luke 6:20 (“Blessed are you poor”) are both expressions of this idea.

The solution: discipleship

In summary, we may split the

causes of poverty into three main categories: poverty caused by personal sin

(chaser); poverty caused by calamity (ebyon and dal); and

poverty caused by oppression (ani, anaw and rush).

Discipleship changes the poverty

caused by personal sin. Membership in God’s

kingdom brings love, releases guilt, heals bitterness, and breaks the power of

drunkenness, immorality and gambling. It results in a new motivation for work;

our response to such poverty must be to live among the poor and preach the

gospel by deed and by word (see Chapter 9).

Discipleship changes the poverty of the frail and the weak, for true disciples will aid the widows and orphans, welcome the stranger and the refugee, and help the destitute. God’s power can heal the blind and the deaf. Our response to such poverty is relief, economic projects, and protection of the weak (see chapter 10).

Discipleship also changes poverty

caused by oppression, injustice, and exploitation. Disciples defend the

oppressed poor by bringing justice (see chapter 11).

In the context of poverty, the

gospel is a gospel both of judgment and of mercy. To the rich and oppressor it

is a message of judgment and woe, requiring repentance. As Jesus says:

Woe to you that are rich, for you have received your consolation. Woe to you that are full now, for you shall hunger. Woe to you that laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep (Luke 6:24–25).

But to the poor the gospel is a message of hope, if they would but repent and believe:

Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden and I will give you rest... (Matthew 11:28).

To the poor, the gospel is a message of blessing, both now and in the future:

Blessed are you poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you that hunger now, for you shall be satisfied. Blessed are you that weep now, for you shall laugh (Luke 6:20–21).

The poor receive the kingdom gladly now. But there will come a day when all oppression will cease and the unjust receive their dues. On that day, the poor will laugh and leap for joy, for each will have his mansion. There will be no more pain, no more sorrow, no more tears!

Blessed are you poor, for yours is—and shall be—the kingdom of God!

Notes

World Council of Churches, 1977.

2.Conrad Boerma,

“Rich

Man, Poor Man—and

The Bible”

SCM,

London 1979. Chapters 2 and 3 have a brief summary of the

themes in the Bible related to poverty including a brief contrast

between ptochos, the beggar, and penes, the industrious poor

man.

3.F. Landa Jocano, Slum as a Way of Life, University of the

Philippines Press, Quezon City, 1975, p 31.

4.Figure from a description of the Tatalon Estate Zonal Improvement

Project, furnished by the National Housing Authority, Quezon

City.

5.Donald Denise Decaesstecker, Impoverished Urban Filipino Families,

UST Press, Manila, 1978, p.126. An in-depth study of the

structure and problems of impoverished slum families in one of

Manila’s

slums.

6.F. Landa Jocano, op cit., chapter IX, “Deviant Females.”