Urban Leadership Foundation

A hub for leadership training in cities and among the world's 1.4 billion slum-dwellers

Reference: Miller, R. "Building Homes and Hopes in a Brazilian Slum."

They were flooded out of their homes, herded from one inadequate holding center to another, and denied assistance for months by a recalcitrant government. But when community organizer Severino Ramos learned of their plight, things began to change.

It was not unusual to hear rain during the night. But on this night, the constant pelting against her flimsy shanty woke her up. It was 4 a.m. Angelina Lopes looked at her floor. There was water everywhere.

"I was terrified," she recalled,

thinking back to that night in February 1992. Water, already ankle deep, had soaked everything on the floor. Outside, her neighbors splashed noisily in the dark through several inches of water, tightly clutching whatever belongings they had managed to salvage from their homes. Civil defense team workers shouted above the storm to frightened families, directing them to higher ground. Quickly, Angelina gathered a few necessities and herded her family into the night.

Before daybreak, more than 70 families, including Angelina's sat soaked and shaken in classrooms at the Jardim School, up a gentle slope from their rickety, storm-wracked dwellings. They were glad to be there at the time. A month later, with only four bathrooms for all of them, they would feel differently.

Government promises

Angelina and her family had lived in Nova Natal, a sprawling favela (slum) on the northern outskirts of Natal, Brazil, for six months before the flood drove them from their home. Like hundreds of others in recent years, she had come to the city hoping to find work and better conditions for her family. But having little money to begin with, families like Angelina's often wind up lighting wherever they can, erecting shelters out of discarded scraps of wood, metal or cardboard and hoping the weather is kind.

With a hard head, keen mind and soft heart, community organizer Severino Ramos is ideally suited to his work.

With a hard head, keen mind and soft heart, community organizer Severino Ramos is ideally suited to his work.

Having arrived in Nova (new) Natal during a drought, Angelina and her family had no idea that they were building their home on a lake bed. Others had built there before her; it seemed like a good idea. But one hard rain in February made them realize their mistake.

Government officials promised to help the displaces with new housing. But it would take time. Not long, they said. Maybe three or four months. After the first month camping in the Jardim School, the families were moved to the Joao Claudio Machado Sports Center, a cavernous, barn-like structure a few kilometers away. It would be temporary, government officials told them. Three months, at the most.

Conditions at the sports center were better in some ways than they had been at the school, mainly in that the families had more space. But they were worse in other regards. Residents had fewer toilet facilities, for one thing.

And they had to endure constant harassment from

local youths who were

angry that their recreation

site was occupied. Frustrated young people hurled stones through windows, and on

one occasion fired shots into the center, hitting a 25-year-old man in the

chest twice. The man survived, but the families inside remained terrified for

weeks afterwards, wondering who might be next.

"Anyone who lived in that sports center has experienced hell," said Maria Das Gracas Regia, who lived there with her family while waiting for government assistance. "One half hour would be enough for anyone."

As three months turned to four, then five and six, the families in the sports center grew frustrated and suspicious that the government's promises had been hollow. Some of them even considered tearing the sports center down and building new homes on the spot. But, as squatters with no land to their names, they had no leverage, no clout with the government to make it adhere to its promises. They might still be lingering in the squalor of the Joao Claudio Machado Sports Center today if it had not been for Severino Ramos, a local community organizer with a reputation for being hard-headed and relentless in battling the government on behalf of the underdog.

A heart for the underdog

The machete blade came down swiftly, slicing the top off a coconut from a palm tree in Severino Ramos' back yard. Fleecy clouds drifted across a cobalt sky in the still morning air. A dog barked in the distance. Three other coconuts were hacked open and their

sweet, cloudy water was poured into glasses for Severino and his guests, seated at a small wooden table in the shade of his house. Severino took a drink and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand.

Compact and solid, with a shock of wavy brown hair and a ready smile, Severino Ramos is no stranger to struggle. "It's in my blood," he said. Both

his father and grandfather were community organizers. And their blood - as well as Severino's - was spilled more than once in an underdog's defense. A person with such gritty determination and tenacity in the face

of a recalcitrant government was just what the stranded families in the sports center needed to get them out of their predicament.

Overcrowding, inadequate facilities and random gunshots made their life a nightmare in the sports

arena.

Overcrowding, inadequate facilities and random gunshots made their life a nightmare in the sports

arena.

"I face discrimination from the authorities because I don't play into their game," Severino said. Neither did his father. "My father had a lot of courage. He became involved in labor rights struggles when he was 16. He

had a heart for the underdog his whole life. He had the courage and leadership

ability to face the authorities. But it earned him a reputation for being a troublemaker."

On many occasions, Severino and his siblings saw their father Pedro come home bandaged from a fight with a thug labor bosses had sent to rough him up. As they grew, their father's reputation extended to his children. Sons of Pedro's opponents often challenged Severino and his brothers.

"I was like my father," Severino said. "I'd fight anytime. When I was young, I injured many boys who would challenge me because of my father. I would pretend like I didn't want to fight, but I would always be prepared. Then, very quickly, when they weren't watching, I would stab them."

He once nearly killed a youth who had been commissioned to beat him, taking a bite out of the young man's neck in an attempt to sever his jugular vein.

As his fights became more violent, he realized something had to change before he wound up dead or in prison. It was then that he met Flavio, a man who saw that if Severino didn't turn his life around, he probably would meet the same fate his father had 10 years earlier: fatally shot and stabbed by a former rival.

"I needed something in my life that would help me change my behavior," Severino said. "Flavio said to me, 'It would be good for you to be a Christian. God will help you change your life.'"

An advocate of justice

While attending a Baptist church in Natal, Severino dedicated his life to God. "I felt God's presence, and made a commitment to serve God."

Despite growing up with a father heavily involved in community work or perhaps

because of it - Severino had had no desire to follow in his father's career

footsteps. "I didn't want to be involved in community development. But when I became a Christian, that changed things."

His friend Flavio pointed out that Christ was a strong advocate of justice and equality. Realizing this stirred Severino's interest in helping those whose rights were constantly being

trampled in one injustice after another. He saw how people had been manipulated by the government, and realized

that such practices ran counter to what Christ taught about the dignity and worth of each person.

In 1982, Severino moved into a modest home in Nova Natal, where he lives with his wife and three children. Since his arrival, he has been involved in various forms of community development and assistance. Since 1985, he has served the community as president of the Nova Natal Residents' Association.

The grassroots organization was formed initially by a group of women who had became disenchanted

with the bureaucracy of the more formal, government-affiliated Community Council. Initially, Severino had himself been involved with the council, but irregularities in accounting and a variety of other problems caused him to leave that group and take up the cause of the newly formed Residents' Association.

In the years since its formation, the Residents' Association, under Severino's leadership, has earned the respect not only of the community, but of civic leaders, who have had to con- tend with a number of residents' demands put forth by the association.

"We face many obstacles," said Severino, "but I persist. This, I feel, is my purpose."

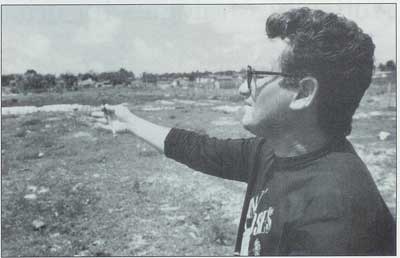

At the flood site, Severino describes how torrential rain devastated residents' homes.

With help from Urban Advance

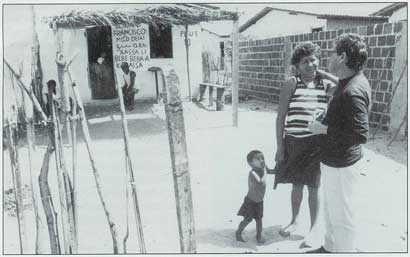

Today, Angelina Lopes and more than 40 other families flooded out of their lake

bed dwellings have decent housing, thanks in large part to the persistent pressure put upon civic authorities by the Residents' Association, with assistance from World Vision's Urban Advance program. A late afternoon walk among their turquoise and pink stuccoed homes finds children playing impromptu soccer games on cobble- stone streets, neighbors casually chatting on doorstep, and the welcome aroma of dinner cooking.

For several years, World Vision's Urban Advance program has worked alongside Severino and the Residents' Association, standing with them as they

faced bureaucratic challenges that stood in the way of the community's progress.

"I feel a lot of support from World Visio," said Severino. "They have been very

helpful."

With the help and encouragement from Urban Advance, the Residents' Association

has been instrumental in getting potable water, paved and street-lights and

police protection for Nova Natal residents. But more challenges lie ahead. Among

the most pressing, according to Severino, is home owner for the residents of

Navo Natal.

"Severino and the Residents' Association were very helpful," said Angelina Lopes.

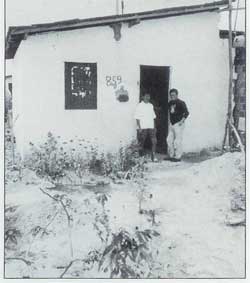

Ana Maria de Lima, who was among the lake bed residents flooded out of their homes in early 1992, talks with Severino in the front yard of her new home in Nova Natal.

"We are glad that many of these people now have adequate homes," Severino said, walking along one of the neighborhood's streets. "But they still don't have deeds of ownership. If they don't have ownership, the government can still manipulate them."

Until ownership can be achieved, the residents at least have protection from the kinds of storms that wiped them out in 1992.

"I thank God for this place"

"If I hadn't received help from Severino and the Residents' Association, I'd have had to return to the lake bed," said Angelina. Although others have taken up residence there since then, none of the families who have relocated have had to return.

"I am very happy I am here," Angelina said, smiling. "I thank God for this place. I am not suffering anymore since coming here."

Although frustrating and sometimes even dangerous, the challenges of recent years have been enlightening for Severino. "I've learned a lot from these experiences," he said, watching children laugh and play on a quiet street while birds chirped in the background. "Now I know what my father had to face."

He smiled and added, "I believe in God, and what God can do for me, and for

these people."

© Viv Grigg & Urban Leadership Foundationand other materials © by various contributors & Urban Leadership Foundation, for The Encarnacao Training Commission. Last modified: July 2010Previous Page |