Urban Leadership Foundation

A hub for leadership training in cities and among the world's 1.4 billion slum-dwellers

Point of Attack

DISCERNING A MINISTRY STRATEGY

Reference: Grigg, V. (2004). Companion to the Poor. GA, USA: Authentic Media in partnership with World Vision.

We knew of no missionaries who had chosen to work among the squatters and plant churches. I began searching among aid agencies for patterns or models of ministry. I looked also at the lives of people of God in history who had walked the path of poverty.

A friend had studied the work of the Salvation Army. We enthusiastically discussed General Booth’s original scheme for reaching London in the 1890’s and its applicability to Manila in the 1980’s.1 I laughed at the difference between Booth and myself. He was tough. He came from among the poor. He was an evangelist. I am not tough, and I find it hard to live among the poor, let alone to minister effectively to them.

As a result of this discussion, I visited the leader of the Salvation Army Social Services. He was a sandy-haired Englishman dressed in the century-ancient Salvation Army uniform. He was flanked by beautiful, smiling Filipino faces, all in similar English-style uniforms. Such is the amazing Filipino adaptability and capacity to integrate other cultures!

Apart from certain cultural anachronisms, I was deeply impressed by their work in the slums. It was small but effective, combining vocational training with Christian ministry.

A year later, I had an hour with this man of God when a bus I was on broke down. I boarded the next bus, saw his familiar white face, and squeezed into a neighboring seat. As I listened to his story, I learned about saving people’s souls and transforming their environment.

Kagawa of Japan

But my biggest

encouragement was the life of another who had suffered no encouragement at

first: Kagawa of Japan. His life gave me a realistic model of how to integrate

evangelism with the fight against poverty.

Over the years, my hall of fame has grown to include the lives of Calvin, Finney, Booth, Wesley, Assisi, Xavier, Mother Teresa, and many others committed to the poor.

There are marked differences in the lives of these people. Yet all understood the centrality of preaching. And all understood the necessity of focusing on the poor as a priority.

Kagawa, Assisi, and Xavier lived as poor men among the poor. Booth, Wesley, and Calvin chose simple lifestyles. All moved from lives as pure evangelists to become evangelistic social reformers: fighters against sin and fighters against poverty and social injustice at every level of society.

Kagawa began with a commitment to identification, choosing to live in the slums of Shinkawa. But he soon realized that a “spiritual” approach of preaching and teaching alone was insufficient. Those early years, however, were full of the essential experiences of identification. Through the positive response to his work in these years, the next phase of his work was founded.

From pure evangelism, he started a small dispensary and distributed food to beggars. During a time of study in the United States, he realized that he must work at the level of social reform if he was to rescue these slum people.

He had been so busy working among the slum people that he had not thought about dealing with the problem of the slums themselves.

When he returned to Shinkawa, he saw that, although much had been done, many of the things for which he had labored so hard had been lost. The mission was continuing, but without his personal active interference on the side of righteousness, young people had failed to withstand the forces of evil. Three of the girls had been sold as prostitutes and 40 of the boys were in prison for theft and other crimes. These things deepened his convictions that the problem of poverty itself would have to be tackled.

Where people were undernourished and their hours of work long, tuberculosis spread. Kagawa knew that work hours had to be shortened by legislation. Prostitution was a consequence of poverty. Poverty must be dealt with if he would save young believers from returning to this lifestyle. Drink was an escape mechanism. Exploited workers needed reformed legislation.

“We must get rid of poverty . . . force the Government to acknowledge the workers’ rights to form unions . . . sweep away the slums,” he preached.

There was embarrassment, anger and hostility. Talk about political action or economic schemes and the reply was always the same: “It isn’t the job of the church.”

Kagawa saw that his future was bound up with three demands:

(a)

He must show that Christianity was not remote from

the joyful yet dirty business of daily living. He could

only demonstrate this by continuing to live in the

limiting, sordid environment of Shinkawa.

(b)

Besides demonstrating practical compassion, he must

go out in the name of Christ and try to find some

solution to the labor problem of Japan.

(c)

In doing so, he would alienate many of his fellow

Christians, and expose himself to official wrath.

From this point, he rapidly became involved in the establishing of trade unions—at a time when they were yet illegal and strikes were still illegal. The power of his leadership was seen in his ability to control strikes with his preaching as much as his readiness to speak in favor of them. His preaching of non-violence enabled the movement to remain out of the hands of the communists at critical points. It was this that finally permitted peaceful negotiations for the existence of trade unions in Japan.

Kagawa, in speaking to laborers, left no doubt of his own position. “Unions are necessary,” he said. “But labor problems can only be solved by a change in the heart of the laborer himself.”

Kagawa went on to deal with the cause of urban poverty—rural poverty—and many other major social and political projects. But never did he lose his primary cutting-edge as a preacher of the cross of Christ. He eventually stood before the Emperor of Japan to preach the gospel.

Assisi, the great 13th century evangelist to the poor and disciple maker of the rich, was also a wandering evangelist. He, too, was a social reformer, whose preaching led to economic repentance. At one time in his own strife-torn city of Assisi he acted as arbiter between the two factions that rent its peace: the rich, the majores, who were in conflict with the poor, the minores.

The document drawn up between them compelled the rich to consult the poor in making agreements with other cities. The lords, in consideration of a small, periodical payment were to renounce all the feudal rights; the inhabitants of the villages surrounding Assisi were to be put on a par with those of the city. Foreigners were protected, the assessment of taxes was fixed, and the exiled poor were allowed to return.2

“Do we save men’s souls or save their environment?” How often have I heard this question—a question that shouldn’t even be asked? Theologians put it in more abstruse terms: “Do we work for the transformation of the individual or the transformation of the structures of society?”

These questions come from the Greek separation of mankind into spirit and body. The Hebrew people, who shared Jesus’ concept of life, knew no such dichotomy.

As if, Kagawa had a choice! He began changing individuals. He soon recognized he must change individuals and the environment that holds us in our bondage.

Did I have a choice between saving souls and saving bodies when a vacant lot beside my friend’s house was covered with rat-infested garbage? The politicians had called a meeting, discussed the need, and even had a garbage pit dug, but still the field of garbage grew. I asked the Christians to bring shovels. For a whole morning, we shoveled the putrid rotting food, the rusty cans, the small snakes, cockroaches, ants and poisonous centipedes into the hole and set it alight.

A lady approached from a neighboring house, “O praise God!” she said. “Last night I prayed, ‘Lord, I am unable alone to shift this rubbish.’ But day after day, the winds blow its disease into my small house. Now, here you are an answer to prayer.”

I smiled and told her, “Yes, God is so gracious, isn’t he? He wants us not only to be free from the rubbish of the sin in our hearts, so we can be saved; he also wants us to be free from the rubbish in our environment, so we can live! He wants us to be rulers over our creation!”

Still the trucks promised by the politicians did not arrive. These squatters had no bribe money; rich businesses did. The garbage filled the field again.

One prayer meeting night with other young squatter believers, I felt constrained to pray that God would completely get rid of this rubbish beside my friend’s house.

The next day, workers came. They got rid of the garbage and posted a large sign: “It is forbidden to throw rubbish here: fine P100. Signed: Barrio Captain.”

We are called to

save souls. We are called to save the bodies of the children who get sick

through the disease of a garbage dump. There is no choice between souls and

environment.

The primacy of

proclamation

While avoiding

the traditional errors of our evangelical heritage in “spiritualizing” the

kingdom of God, a commitment to the scriptures needs, on the other hand, to

beware of the other end of the pendulum. The final aim of mission is not

socio-economic-political change.

One day, I curled up in a soft chair in the magnificent Manila Peninsula Hotel. (At times, I would take a whole day off to get some peace and quiet, and again experience air-conditioning and Western culture. Everybody assumed I was a tourist. God gives us all good things to enjoy!) This day I read right through the Gospel of Mark to see if there was any way, I could accommodate the teaching that the aim of mission is socio-economic-political change.

There was no way. The Gospels are clear. The establishment of the kingdom is accomplished not primarily by political change, economic change, or social change. It is accomplished by people preaching the good news that the kingdom of God has come. The kingdom comes as people repent of their sins against God, of their economic exploitation and their social hatreds, and submit themselves to the teaching of the King. Demonstrations of spiritual power, seen in spiritual gifts of healing and power over demons, accompany this proclamation.

As a result of proclamation, new communities of believers form within towns and cities. These communities often will be persecuted, and politically will not be powerful. But they are to act as salt does in meat and be a sign of righteousness.

Unmet needs

I began to ask

questions and discovered that official and unofficial estimates of the

squatter and slum population range from 1.8 million to 3.6 million—30-40% of

Manila’s population, growing at a rate of 12% per year.

We found ten evangelical aid programs among these millions. A number of churches also had extension Bible studies into the slums. A few local Catholic priests lived with the poor. But of the more than 400 missionaries living in Manila, not one was actually living among the poor.

After eight years of searching, we have found just six Filipino pastors who have lived in these slums and established significant churches. That is one church for every 500,000 squatters—equivalent to one church for the entire state of Alaska. What further reason is needed for a life of proclamation and identification with the squatters of the slums of Asia?

Most Christian agencies to the poor had been captured by the social work concept: the basic issues are the economic issues; the entrance point is economic programs. One should only attach an evangelist to such programs, and have Bible studies for the recipients of the aid, after the economic need has been met.

This error of many evangelical aid agencies appears to be not so much theological as tactical. The entrance point into communities in the scripture is not aid programs, projects, or good deeds. It is the breaking down of demonic powers by the proclamation of the cross. This is accomplished in the context of doing good deeds and results in spiritual change, which in turn transforms social, economic and cultural values.

Because of their deep commitment to the proclamation of the gospel, the Salvation Army has a fine balance between the social and spiritual in their work. They see their social work as a pastoral component of ministry, and only begin after the establishment of a local “corps,” usually a year later. Even in community projects among the people, their workers always see Christian salvation as the priority. Their vibrant passion for seeing people turn to God is balanced with the expectation of economic transformation following spiritual transformation.

Any disciple with a burning sense of mission must proclaim the kingdom. Economic programs may be added in any number of ways to such a person’s work, but the power of proclamation is the essential starting point for any growth of the kingdom.

There is no question of spiritual versus material. The kingdom is holistic. But a definite set of priorities brings about socio-economic-spiritual change in a community:

1.

Proclamation leads to disciple making.

2.

Disciple making leads to pastoral issues.

3.

Pastoral issues result in building a new social

structure where economic needs can be discussed

and enumerated.

4.

A new social structure involves dealing with

politicians and seeking changes in public policy or

political personnel.

What about social work?

Social work and community development are, indeed, significant areas of Christian activity to the extent that they are reflections of biblical teaching on social relationships, financial dealing and political action. Workers for the kingdom of God can work with government and private agencies working in the squatter areas.

At the same time the kingdom comes violently (but not by violence!), so that its truth may at times create disharmony. People persecute Christians for living and preaching the truth (John 15:18-25), which according to their standards, is a violation of professional humanistic social work ethics.

Social situations

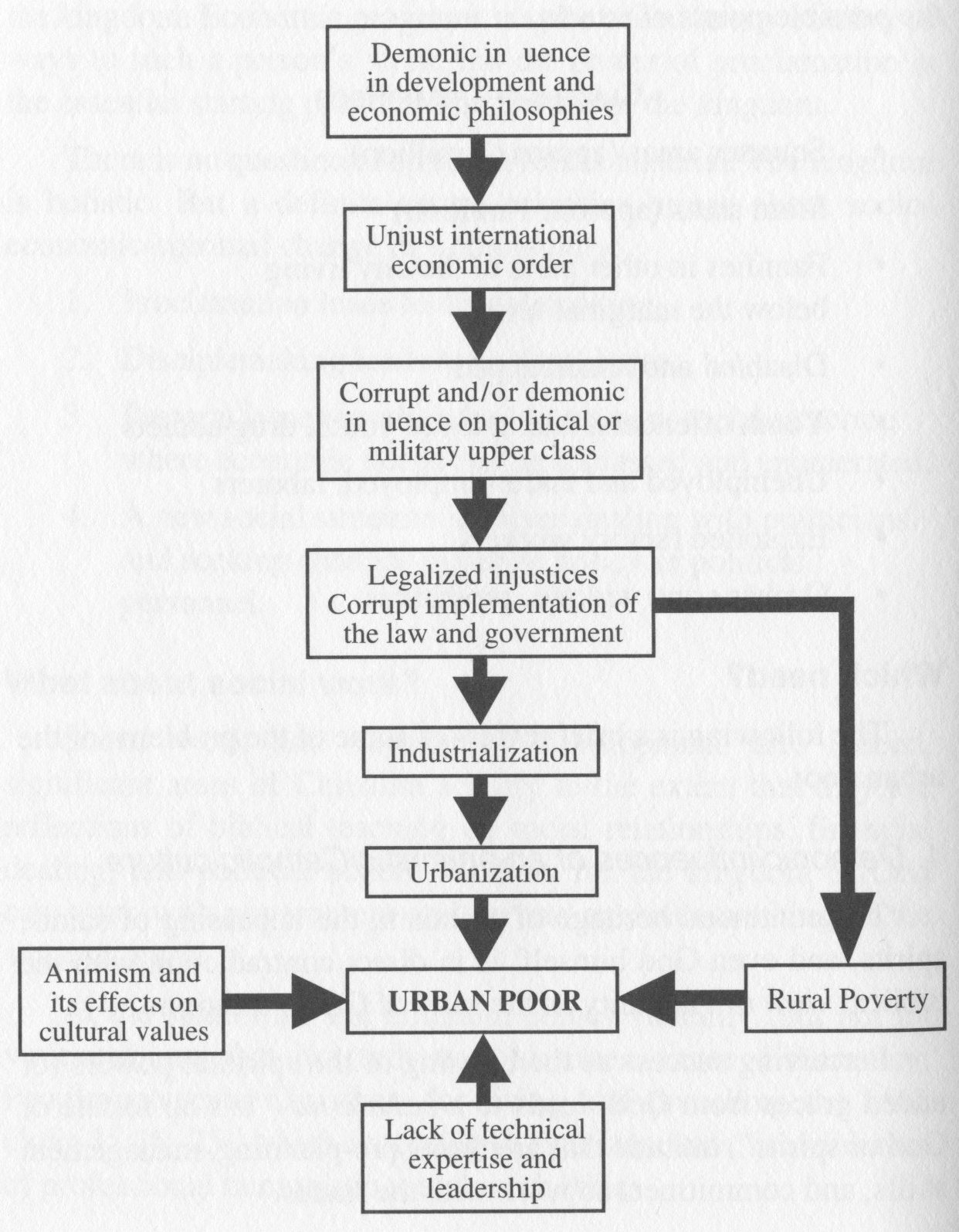

Having determined the primacy of proclamation, we still need to discern how and when to grapple with broken social structures, inadequate economic opportunities, and corrupt political structures. The following list shows some of the possible points of attack.

Classes of Urban Poor

•

Squatter areas (approx. 2 million)

•

Slum areas (approx. 1 million)

• Families in other parts of the city living

below the marginal level

• Disabled and handicapped

• Youth offenders, unemployed youth, drug addicts

• Unemployed and under-employed, laborers

• Exploited factory workers

• Orphans and widows, prostitutes

Which need?

The following is a brief review of some of the problems of the urban poor.

1. Demonic influences of an animistic/Catholic culture

The continued heritage of animism, the appeasing of saints, spirits, and even God himself, is in direct contradiction with the biblical view of humanity as the ruler of God’s creation.

Perceiving success as the blessing of the spiritual powers (or added graces from God) leads to a bahala na (“it’s up to fate or God or spirits”) attitude that precludes pre-planning, management skills, and commitment to work with the hands.

Worship of saints, use of curses, prayers to the dead, and other practices often are related to sickness and emotional disturbances.

Points of Attack in the Fight against poverty

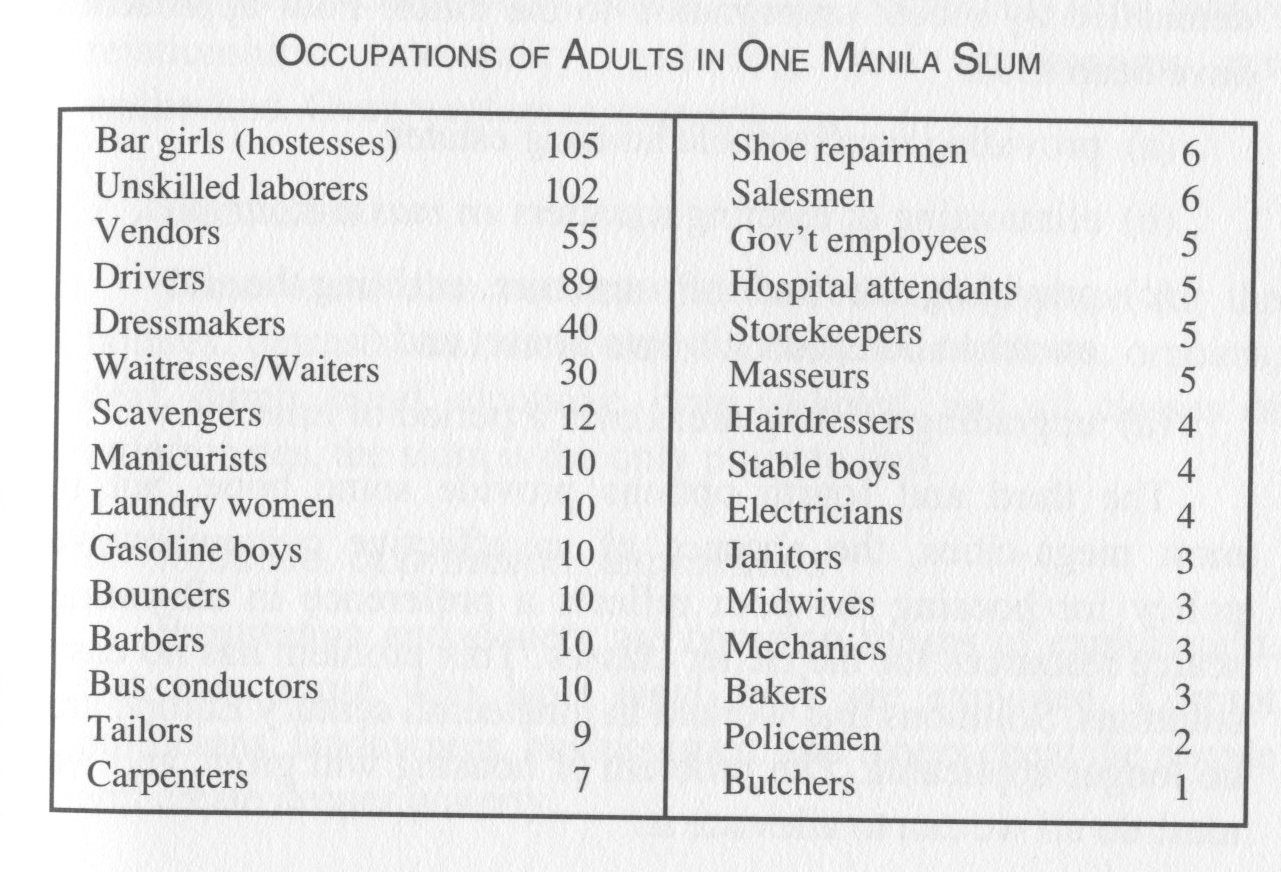

2. Unemployment

Basic to the meeting of most needs is the need for income. A survey of 1,5OO adults over fifteen years of age in one established slum in Manila showed that 1,191 of them

or 68%, were unemployed.3 The remaining 32% were employed in the following occupations:

Occupations of Adults in One Manila Slum

Notice in the above industrial context, the number of tradesmen consists of seven carpenters, four electricians and three mechanics—a total of 14 workmen out of 558, or a mere 2.5% (assuming that all the above were in fact skilled). The statistics reveal one of slum’s critical needs: the introduction of practical trade skills.

3. Inadequate housing

Filipinos call them “squatters,” which aptly describes the insecurity of the new city migrant. Too poor to purchase land and build a house within a reasonable time, unwilling to pay rent for decaying accommodation or perhaps unable to find a room for his family, the migrant is forced to illegally occupy land. He becomes a squatter on land in dispute, unused public land or buildings, frequently flooded land, or land beside railway tracks.

Two-Thirds World communities have neither the money nor the technical skills to mount a housing program on the scale demanded by recent immigration to the cities. Four approaches have been tried:

(a)

providing unaffordable housing estates;

(b)

eliminating or ejecting squatters en masse from land;

(c)

providing sites and infrastructure, enabling the site

owner to construct his own house; and

(d)

Upgrading existing areas over a period of time.

The third and fourth options provide some hope, but in most mega-cities, the absence of an effective comprehensive policy for housing the poor reflects a preference in allocating scarce resources for the richer classes. This problem has no easy solutions. Solutions that worked in nineteenth century Europe are no longer applicable. The problem of housing will grow, and we must do all we can to alleviate it.

4. Unsanitary environment

The fact that squatter housing is illegal means that garbage collection, sewerage, water supply and electricity have to be obtained illegally or informally. Unsanitary conditions cause frequent sickness. Malnutrition further adds to the sickness and death toll.

5. Lack of education

Whether or not education is available, families cannot afford to send their children to school. Working, as opposed to school, meets a more immediate need—money. Lack of elementary education destroys any future of higher education or better employment.

6. Broken social structure

The uprooting of millions from their provincial roots into an environment lacking traditional social controls leads to an almost total breakdown of moral values, community, and family relationships. Immorality, gambling, and drunkenness run unchecked. Gang warfare is frequent.

7. Destitutes

These areas also become the final dwelling place for the failures, outcasts, and dropouts of society. For widows, orphans, deaf, dumb, blind, alcoholic, drug-addicted, and all classes of unfortunates, the slum is the only place to live.

8. Injustice, oppression, exploitation

Prostitution and slavery are common means of exploitation. But even those who have legal work are exploited. Corrupt politicians, landowners, businessmen, and others cheat the people and create deeper poverty.

9. The future

This trend towards urbanization may slow down. However, the immediate future shows no evidence of any solutions. The problems will grow for some time.4

Proposed measures of rural development are not likely to stem emigration from the provinces to the cities. The prevailing patterns of economic dependence of the Two-Thirds World nations on the industrial nations will perpetuate and increase the social inequalities within poor nations. Radical structural reforms may be difficult to bring to completion due to the status of dependency on the developed world. The very scale of the problem is beyond what most governments can cope with. Efforts are likely to be concentrated in a few areas to the neglect of the remainder.

The slum and squatter communities themselves will slowly change. Immigrants will be better educated than those of former decades, and the proportion of second-generation squatters will increase.

The state and para-state bureaucracy will not be able to create jobs for more than a minority of migrants and primary school dropouts. Most will have to be absorbed into the informal sector—into small-scale labor-intensive activity, poverty and patronage, dependent on the formal sector, working long hours for low financial return.

Mobility through education is likely to be slight, as is the chance of upward mobility in the entrepreneurial sector.

Yet the people will continue to hope. The story of the local boy who has “made good” will have more influence than statistics indicating the improbability of success.

Notes

1.

General William Booth,

In Darkest

England and the

Way Out,

Amazon Press, 2001.

2.

Paul Sabatier,

The Road To

Assisi: The Essential Biography Of St. Francis,

Jon Sweeney, ed., Paraclete Press, 2004.

3.

Landa F. Jocano, Slums as a Way of Life, University of the

Philippines Press, Quezon City, 1975, p 31.

4.

These thoughts are summarized from Peter Lloyd, Slums of Hope

Shanty Towns of the Third World, chapter 9, Pelican Books, 1979. Reprinted

by permission of Penguin Books Ltd. More recent comprehensive research on the

nature of the slums, is available in UN-Habitat, The Challenge of the Slums:

Global Report on Human Settlements, Earthscan Publications, 2003.

© Viv Grigg & Urban Leadership Foundationand other materials © by various contributors & Urban Leadership Foundation, for The Encarnacao Training Commission. Last modified: July 2010Previous Page |