Urban Leadership Foundation

A hub for leadership training in cities and among the world's 1.4 billion slum-dwellers

The Migrant Poor: Who Are We?

Reference: Grigg, V. (2005). Cry of the Urban Poor. GA, USA: Authentic Media in partnership with World Vision.

The way to the Celestial City lies just through this town, where the lusty fair is kept; and he that will go to the City, and yet not go through this town must needs go out of the world.

— John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress

One was a big man with a good education, speaking English fluently with an English accent. The other was a Nepalese, small in stature but full of big dreams.

“What business would you get into if you were to make it off the street?” asked my friend, a Kiwi businessman.

“We would establish a tea stall,” they replied.

Several further discussions led to a conclusion

that it was a worthy goal for $100. But to find a piece of unoccupied street

took 10 days. They only had to pay the police a reasonable two rupees each day

for protection. But paying the local mafia cut their profit margin to zero.

A daughter fell sick from a fever. She had been

caught in the rain without good blankets in the cold Calcutta winter. This

crisis slowly consumed their financial capital.

Unable to pay the mafia, members of the family

were beaten up.

City of joy

Calcutta, oh Calcutta! City where the powers of

darkness have so gained control over the political and judicial leadership that

only darkness prevails, and a mafia rules the city’s people. Poverty and evil

triumph and infest the lives of ordinary people until they go crazy with the

pain.

Calcutta has more poverty and more grades of

poverty than any other city in the world. I walk down the street, and a well-fed

wraith-like figure, baby on hip, comes after me pleading, pleading. There are

four of them fighting each day for this territory. An amputee shakes his cup on

the corner, an old man lies on the path further along, near death.

In 1984, Geoffrey Moorehouse estimated that

there were 400,000 men in town without a job,1 the 1981 census put it

at 851,806. Ganguly comments that perhaps no other city has one million educated

youth registered with the employment exchanges.2 there is beggary

all over India, but nowhere is there beggary on the scale of Calcutta’s.

Beyond the beggars are anywhere from 48,000 to

200,000 people who live permanently on the streets. One survey shows that

two-thirds of them have some kind of regular employment, while 20 percent are

beggars. Most have some kind of part-time work or have earned money by selling

vegetables, paper, firewood and scraps.

More than half of the 3.5 million living within

the metro core are slum dwellers. Two-thirds of Calcutta’s families earn 350

rupees or less a month (the poverty level is Rs600 or US$50 per month for a

family). Less than 20 percent of its workforce works in an organized industry.

Agriculture and small crafts, not major or modern manufacturing, are the

principal occupation of the people. In as much as 80 percent of its extended

land surface of 1,350 square kilometers, there are 3.15 million bustee

and slumdwellers.3

There is a level of poverty still lower than

that experienced by beggar, street-dweller or bustee-dweller—the poverty

of those who are approaching death. The dying are faces along the streets. An

old man, his eyes fixed. Some passers-by leaving a few coins. A visit with the

Brothers of Charity to the street-sleepers under an unfinished overpass. A

plaintive plea from a silver-haired mother shivering violently with fever for

some coins to buy medicine. Behind her, two pot-bellied little boys displaying

their first-degree malnutrition.

Calcutta daily demands that we face not just poverty, not alone inhumanity, but this gray face of approaching death. The burden is increased by the knowledge that the continued over fertility inherent in poverty will force five times this number of people off the land in the next generation (about 20 years). The fact is that there is no more land, no more subdivision of farms possible. Increased agricultural productivity will only add to the migration, for it will increase the number of living children without bettering the quality of rural life.

The constant bickering of Bengali politics is

death for these poor, as is the economic dislocation introduced by a

theoretically Marxist state government—in reality a continued domination by a

rich ruling class. The perpetual bondage of Hindu caste and culture adds to the

death.

The task ahead

Into this scene Jesus speaks the words, “And this is eternal life, to know him” (John 17:3). The confrontation with death involves aid, development, organization, politics. But as the brilliant Francis Xavier learned early in life, the issues of this world are not determined by politics and force, but by the mysteries of grace and faith. In the preaching of the cross comes the vanquisher of this slow death that grips the city. Eventually it must be movements of the righteous who can turn the flood tide. The question is how to generate movements of disciples among these poor and subsequently among the rich.

Defining poverty, its types, causes and potential responses, is an important step in the process of generating such movements. An understanding of the breadth of need and the range of potential responses enables us to reflect both on theology—that is, God’s responses—and on strategic possibilities to implement as we walk with God.

Some levels of urban poverty

It would be a mistake to consider that the poor are to be found only in slums or squatter areas. Or that the people in the slums are necessarily all poor. Slums and poverty are not to be equated. And even among the poor there is a class structure or ranking. What then are the relationships between squatters and poverty?

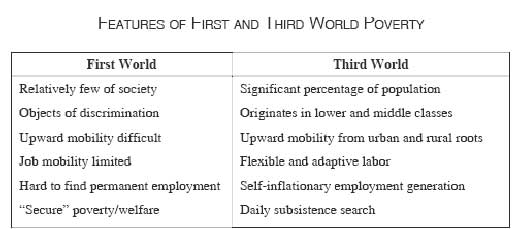

Differences between first and Third World urban poor

Absolute poverty

is a term used to describe poverty when people

have an absolute insufficiency to meet their basic needs—food, clothing,

housing. Indeed, many who are in absolute poverty starve to death. Within this

category there are many levels. For example, we may talk of first, second and

third-degree malnutrition.

Relative poverty

is found in the developed world and is measured

by looking at a person’s standard of living relative to others in the community

or nation. It is sometimes called secondary poverty. It is a measure of the

extent to which people are on the margins of society.

The measure of this relative or secondary

poverty is often in terms not of a material or economic level, but of capacity

to own and consume goods and services and to have opportunities for development.

It is often an exclusion from opportunity and participation, a marginalization

from society.

This marginal status is associated with and

caused by (or causative of) a low material standard of living in relationship

to present social perspectives of how one should live well. To be without a car

in a New Zealand city, for example, means one is poor and largely unable to

participate in society. This is not true in Lima, Peru. An International Labor

Organization study uses a measure of disposable income to establish the

standard poverty line, dividing the total available income in the country by the

population, thus determining this level relative to others within the nation.

Thus when talking of poverty in Third World squatter areas, we are generally talking of something that occurs at a level not even to be seen among the poor of a Western country. The middle class of Calcutta are poorer than the poor of Los Angeles.

The definition of poverty is also, to a large extent, a historically perceived issue. The poor of Manila are not as poor as the middle class of England even 400 years ago. But they are poor compared with the present-day middle class in any country in the world. Our definition of poverty has changed with the availability of technology that enables us to enjoy a healthier, happier life.

Poverty can also be defined in terms of what man and society could be, in terms of a future vision of a reasonable, or ideal, lifestyle. Biblical scholars have recently clustered their definitions around the theme of shalom in the Old Testament—peace that comes out of a just and secures society.

Reachable communities of urban poor

The physical characteristics and culture of each

squatter community differ from country to country. Yet the processes that

generate them and the resultant evils are universal among the major cities of

the Third World countries.

We may talk of three major international

categories of urban poor: inner-city slums, squatters, and specialized groups.

Inner-city slums

are decaying tenements and houses in what were

once good middle and upper-class residences. They may be described as slums

of despair where those who have lost the will to try and those who cannot

cope gravitate. Yet here too are the recent immigrants, living near employment

opportunities, and students in their hundreds of thousands, seeking the upward

mobility of education.

In Sao Paulo, approximately half of the migrant

poor that come to the city find their first residence in favelas, or

shanty towns. The other half move to the corticos (rundown, inner-city

housing), then within four years move down into the favelas. In Lima

these are called tugurios.

In inner-city slums of despair there is little

social cohesion, or positive hope to facilitate a responsiveness to the gospel.

Since they are older poor areas of several generations of sin, they are not

responsive, and hence do not constitute a high priority for church planting.

In terms of response it is more strategic to

focus on squatter areas, which tend to be slums of hope. Here people have

found a foothold into the city, some vacant land, jobs and some communal

relationships similar to the barrio back home.

Slum of hope

Tatalon, in Manila, is an example of one of the

many slums of hope that have sprung up since the 1940s. A total lack of

facilities and services did not deter provincial migrants flooding into Manila.

In the unoccupied lands of Tatalon, they found an ideal site to establish

footholds in the big city. In 1976, the average home in Tatalon contained 12.3

people. There were 14,500 people in about six square blocks—approximately 57,500

people per square kilometer. By 1985, the number of residents had doubled.

Tatalon is one of the more fortunate squatter

areas. The government in the last few years has established a “sites and

services” program, gradually upgrading the area. It has put in roads, a number

of toilets, some water pumps, and surveyed the land. It has organized the people

so that those longest in residence may buy the small lot on which they live.

This upgrading has been done at a cost of between 70 and 120 pesos

(US$3.50-$6.00) per month over a 25-year period.

Tatalon is a place of hope, a slum in which to

dream, to aspire. It is a community that is beginning (with a little help) to

come through decades of suffering into a little economic security. In such a

context the gospel is welcomed as one more part of the social changes people are

going through. It can move like wildfire.

The incarnational patterns outlined in

Companion to the Poor4 are applicable in Catholic contexts

such as the Philippines and Latin America. They are probably applicable as well

in any context where the culture has a positive direction towards Christ. In

contexts moving away from Christ or under severe political control, the

principle of incarnation still holds, but foreign workers may need to work

closely with and train national people while they themselves live outside of

these poor areas. This will lower the profile of the foreigner.

There are other situations where squatter areas

are so destitute that living in them is not a viable option, such as the

squatters in Calcutta (the next three million lower than the bustees).

Geoffrey Moorehouse describes the street people in the heart of Calcutta

For five hundred yards or so there is a confusion of old packing cases, corrugated iron, straw matting, old bricks and wads of paper arranged in a double Decker sequence of boxes. Each box is approximately the size of a small pigeon loft, with room to squat and only just to kneel . . . each box is the sleeping and living quarters of a family. The rest of their life is conducted on the pavement where they cook and play and quarrel together.5

Among these poor the poverty is so intense that the primary response may have to be aid, given in such a way that Jesus shines through and their dignity is sustained. Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity reflect the patterns of Christ in ministering among such poor more than any other ministry I have seen.

Specialized groups

To these categories of poor communities may be added other groups of poor that do not make up a natural community for church planting, but may be reached by specialized ministries. These would include the street people of Hong Kong, Calcutta’s 48,000 pavement dwellers, the 600,000 drug addicts and 500,000 prostitutes of Bangkok, the deaf and lame outcasts of these societies, and the white slave trade between many of these cities.

Some groups of urban poor are likely to be more open than others. Sam Wilson sums up an aspect of this by relating it to the concept of an unreached people:

The urban poor do not necessarily exist as a meaningful group, even in a given locality. Some sense of belonging and community which affects one’s sense of identity will be necessary if the category listing is to be verified as a group that needs a strategy for evangelism.6

Some questions for verification come from this kind of thinking: Is this really a people group in the sense of belonging and community? Do they meet and change one another? Is there a mutual influence on behavior because the individuals sense likeness? Is there a viable church ministering within the people group? Can it carry witness forward? Some of the people groups within the urban slum and potential responses to their needs are listed below.

1. Street vendors

Hawkers, illegally eking out their existence along the roadsides of the crowded streets, pose special problems because of the logistics and the long hours of work they must endure. A strategy based on small groups that reaches a cluster of two or three stalls could be effective. Search would have to be made to determine which hawkers live on the streets with their stalls, which ones are the truly poor, and which ones come from various squatter areas. With this knowledge, it may be possible to locate reachable and responsive clusters. These could then be linked together in monthly fellowships at some inner-city location.

Generally, street vendors work from early morning till late at night, so the time for Bible studies and fellowship have to be carefully defined. It would seem perhaps wiser to reach street vendors from churches planted in the squatter areas.

2. Marketplaces

Public preaching and celebrations should be held in market places two or three times weekly during the early afternoon when the stalls close for siesta. Again, most vendors live in squatter areas, so a squatter ministry would be a better starting point.

3. Street kids

City officials estimate that there are 10,000 abandoned children in Lima. In Sao Paulo, estimates range from 8,000 to 300,000. Antioch Mission in Brazil is a Christian mission giving good leadership in approaches that meet some of these children’s needs, establishing contacts with them on the streets and then developing programs for them with the hope of integrating them into Christian homes.

4. Drug addicts

Of all urban ministries, a ministry to drug addicts requires the tightest authority structure and discipline. The one-to-one discipline process Involved will result in a network of disciples, many of whom, as they become stabilized, will return from the rehabilitation retreat homes (outside the city) to their squatter areas and may become foundational for churches. Among the drug addicts, a discipline movement developed comparable to a Christian gang is possible. This kind of ministry, often linked to a prison ministry, is operating in a number of cities.

5. Alcoholics

Years of experience has been acquired by Alcoholics Anonymous concerning the philosophy and strategy of reaching alcoholics. Its patterns are derived from Christian ministry and Christian values. We need to seek dynamic Latino and Asian equivalents.

6. Prostitutes

The problem of prostitution is at heart related to demonic infiltration of a city’s leadership structures and to severe economic exploitation. It requires a justice-oriented ministry that begins with a grassroots attack through rescuing girls from the houses in which they are trapped.

After working with single mothers in New Zealand for years, Pat Green was called by God to work with prostitutes in Bangkok. During a year of language study, she formed many relationships with girls in Patpong, the streets that are at the center of prostitution in Bangkok. Over one hundred go-go clubs, beer bars, discos, massage parlors and restaurants line the streets and alleys. On any given night approximately 4000 women work here as bartenders, waitresses, go-go dancers and masseuses. Most are prostitutes, and indeed many are forced by their employers to “go with customers.”

From these contacts, and through God calling other missionaries from Singapore and elsewhere, a team called Rahab Ministries formed. Pat also has a gift of relating with women in high places. Many of these are appalled at the sex and slave trade, and are eager to work together, bringing public and legal pressure to bear. In her last letter, Pat said she was considering whether they should rescue, even by buying back, a girl sold for $5,000 into a closed brothel in Japan, as part of international sex trafficking.

7. Deaf, blind, and amputees

Specialized ministries for deaf and blind are needed. In Manila, for example, many blind people are balladeers, going from house to house seeking events at which they may sing and earn their keep. I often have encouraged rich Western performers to take two years to live among them, seeking to generate a movement of Christian blind balladeers in the slums. The sense of dignity that could be generated among these people and the potential impact of such a ministry are great. There is a good man in Calcutta who has developed a card-making shop for amputees. They sell their cards around the world. He has assisted scores of poor in this way.

8. Prisoners

A number of poor people’s churches have formed through ministries to prisoners in different cities. Real conversions and training within prisons can prepare tough men for their return to the squatter areas where churches are then formed through their testimony. It was a thrill to walk back into a community where I had labored years ago and find one of the first converts, Boy Facun. He used to be a man well acquainted with jails. When we were reunited, he had become an associate pastor and was forming a jail ministry team. He preached one evening and fifty made commitments to the Lord. His joy and mine knew no limits, as he told the story.

Finding a responsive community

To initiate ministry among the poor in these

cities, it seems wise to begin movements that first focus on responsive slums

of hope. All kinds of poverty can be found in such a place, but there is an

atmosphere of hope, there is some degree of community relationships, and

communities of Christ that can minister to each other’s needs are easier to

establish.

Within cities we can analyze the responsiveness

of squatter communities according to criteria developed by Edward C. Pentecost.7

Other criteria may be developed. For example, Paul encourages the believers to

pray for peace that the gospel might move unhindered. Thus, finding a community

that has a history of peace is a factor.

The following are some criteria we developed to

select a community that was likely to be more responsive—a community where the

first Servants workers in Bangkok would minister.

1. Size of the slum

About 100 to 500 families (500–2500 people) would provide a big enough community so that the responsive sectors could be reached. These can then influence other sectors. In smaller communities, the whole community becomes involved in decisions. If they reject the gospel immediately, there is no encouragement or modeling that will easily reverse their initial rejection.

2. Peoples from responsive rural areas

In Thailand, we knew that northeastern and northern Thai are responsive to the gospel. In Bangkok, we focused on areas where these people had migrated.

3. Age of the slum

The younger the slum, the more responsive it will be. When people live in a slum for more than five years, their senses become dulled by sin. Younger age groups are more responsive. In new squatter areas, people are more open to new relationships. In older slums, web relationships are more tightly developed.

4. Homogeneity

Slums where there are ethnic or other divisions may not be places where the gospel will easily move.

5. Religious background

Previous exposure to Christianity, outside help and programs, is a factor to be considered, as is proximity of a temple, mosque, or other religious site.

6. Direction or discernment of the Holy Spirit

7. Education, home, and family

Schooling for workers’ children is a priority for families. The level of education in the city is important. In Bangkok, the level of education in the public schools is high. Other family criteria include peace and security, economic level, area for children to play, proximity to buses and other services.

8. Spiritual receptivity

While evaluating some of the natural factors regarding responsiveness, one is able to press on in the task of discerning the spiritual receptivity of a community. Jesus wasted little time on surveys. His commission was to go and to preach. Where there is obvious receptivity, remain in that place. Where there is obvious opposition, move on.

We need to remember, however, that we are faced with the difficulties of entering new cultures, whereas he was dealing with a known cultural context and responsiveness. For us, then, some degree of survey work is appropriate, if it is not overdone.

It is useful to find out the history of the community from the people. The community’s name often indicates a spiritual connection to past events. Is there a history of covenants between people and their gods?

During prayer, and while preaching in these communities, the Lord often reveals, through gifts of discernment, some elements of community history, present spiritual warfare, or future strategy.

Lima: desert capital

The various categories of the poor may well be demonstrated by a look at Lima, Peru.

Once, like Calcutta, it was the center of an empire—Spanish-speaking Latin America. Now it is a city in decay, yet with new life emerging. It is built on a desert, which is a positive factor for the poor, as land is not so restricted a commodity as in other cities. There are several classes of poor in the city, including three classes of their cities. There are several classes of poor in the city, including three classes of settlements:

1. Asentamientos

Asentamientos are homes made with straw matting (estera). The people occupy a vacant area of mountain or desert and build their homes. They are quickly organized so that basic necessities become regularized.

2. Pueblos Jovenes

Pueblos jovenes, also known as barriadas and barrios marginales, spring up and develop without preplanning by government agencies. Initially there are no telephones, streets, or water.

Official figures from 1980 placed pueblos jovenes at 40 percent of the city. Tito Paredes and others estimate 60 percent in 1987, with an added influx due to the terrorism in the Quechua areas.8 Extension of the 1980 statistics with consideration of the depression in the economy in the early 1980’s would give a conservative estimate of 50 percent of the city presently as pueblos jovenes. This figure, as for many figures from different cities, does not allow for the rapid movement into more middle-class levels of many within the oldest barrios as they become urbanizaciones.

Barriadas or pueblos jovenes began to multiply rapidly in 1950, as they did in most other world-class mega-cities. In 1961, legalization of these areas began to occur. In 1970, there was promotion of land title registration. Since the late 1980s, with much political assistance from the new president and the Mayor of Lima, people have been able to get land titles.

In 15 districts of Metropolitan Lima, the population in barriadas ranges from 50–100 percent of the total population. Four of Lima’s 47 districts have over 90 percent squatters. For more detailed data, see the chart below.

GROWTH OF THE BARRIADAS OF LIMA, PERU

|

|

Total City population |

Number of Barriadas |

Population of barriadas |

% of City Population |

|

1922 1940 1956 1961 1972 1981 1983 1985 1990 |

645,172 1,200,000(est) 1,652,000 3,302,523 4,492,260

5,860,000 |

1 11 56

408 598 |

119,886 316,826 805,117 1,460,471

5,500,326

|

9.5 17.2 24.4 32.5

40 38 |

3. Urbanizaciones

Urbanizaciones, or well-planned suburban communities with water, drains and electricity, develop from a-sentamientos and pueblos jovenes. After five years, the government taxes those houses in a pueblo joven that are not constructed permanently. Then development occurs, as lights, water and roads are brought in. Twenty percent of the city’s residents live in regular planned suburbs. Eighty percent live in popular settlements, of which 23 percent live in popular urbanizaciones, 37 percent in barriadas and 20 percent in the tugurios.

4. Street people

Over the last decades there has been a conversion of the economy of the city from a more formal industrial economy (of legally incorporated businesses) to an informal, unofficial street economy. Main players are typically

The street vendors, or self-managing vendors, with the whole family participating in this economic enterprise. This unofficial sector represents 67.4 percent of the total productive economic activity of Lima. Some vendors pay as much as US$500 per month rent for a piece of sidewalk six feet wide.

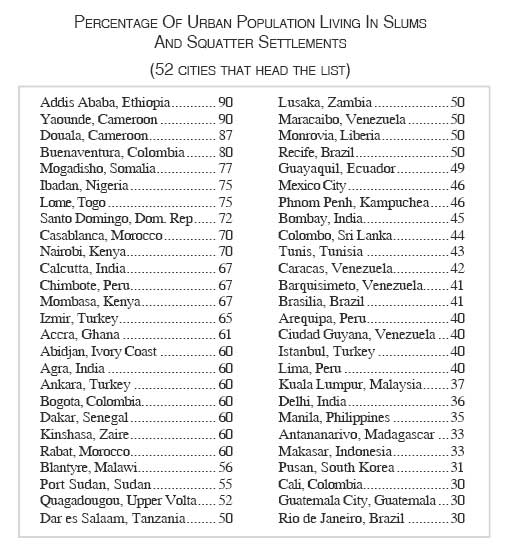

Lack of housing: universal squatter concern

The major criteria defining squatters is the nature of their housing. The chart on the previous page lists the cities of the world that have the worst housing situations. Housing gives an indication of the extent of peasantry in the city. Yet if a city is 90 percent squatters, are they then actually the people of the city? Are cities indeed middle-class, or can there be functioning cities of the poor?

Stratification of squatter and slum poverty

The fundamental economic factor defining

squatter poverty is land. Using Hong Kong as his context, Abrams has typified

squatters partly by their economic relationships to the land:

The owner squatter owns his own shack,

though not the land. He erects the shack on any vacant plot he can find. Public

lands and those of absentee owners are the most prized. The owner squatter is

the most common type of squatter.

The squatter tenant is in the poorest class, neither owning nor building a shack, but paying rent to another squatter. Many new in-migrants start as squatter tenants, hoping to advance to squatter ownership.

The squatter holdover is a former tenant who has ceased paying rent and whom the landlord is afraid to evict.

The squatter landlord is usually a

squatter of long standing who has rooms or huts to rent, often at exorbitant

profit.

The speculator squatter is usually a

professional to whom squatting is a sound business venture. He squats for the

tribute he expects the government or the private owner to grant him sooner or

later. He is often the most eloquent in his protests and the most stubborn in

resisting eviction.

The store squatter, or occupational squatter, establishes his small lockup store on land he does not own, and he may do a thriving business without paying rent or taxes. Sometimes his family sleeps in the shop.

The semi-squatter has surreptitiously built his hut on private land and subsequently comes to terms with the owner. The semi-squatter, strictly speaking, has ceased to be a squatter and has become a tenant. In constructing his house he usually flouts the building codes.

The floating squatter lives in an old hulk or junk which is floated or sailed into the city’s harbor.

The squatter “co-operator” is part of the group that shares the common foothold and protects it against intruders, public and private. The members may be from the same village, family or tribe or may share a common trade.10

Government responses to housing needs

Generally the first attempt by governments when

the problems of squatters emerge is to bulldoze down these areas. Political

considerations then lead to the possibilities of relocating them—usually on

cheaper land outside the city. For example, 900,000 squatters have been

relocated outside of Manila’s boundaries onto land that has a few water wells,

with a toilet for each family. Between 1964 and 1974, an authoritarian

government in Rio de Janeiro relocated 80 communities.

Squatters, while appreciating the new land,

although it may be without water or near shops, cannot build houses in such

places because they are too far from their places of work. Most return to the

city.

The next approach governments have tried is to

provide high-rise apartments at low rentals for the poor. In Chinese cities,

with millennia of urban experience, this has worked. Elsewhere, it has been

catastrophic. High-rise apartments are too expensive for the poor to rent, so

they are rented by middle-class officials, and the poor again are forced to find

new squatter areas. A variation on this has been to construct low-cost,

single-story dwellings.

The emergence of various forms of self-help

development has been the most effective long-term solution. Either the squatter

area itself is upgraded, by introducing legal titles to land, water, sewerage

and electricity and by encouraging the people to construct their own homes of

solid materials, or a new site is located and these basic services are

introduced before the people are relocated. The World Bank recently set aside

large sums of money to assist governments in this latter kind of program.

Possessions of the poor

It was her first full-time job as a secretary. The income upgraded the family’s diet, then carefully week by week a little was set aside to buy the TV set. It took two years of skimping and saving before it was bought. They proudly showed it to me each time I returned to the community. This was the first step into the middle class—a status symbol and a source of delight after years of struggle.11

Oscar Lewis’ work gives us a concrete glimpse of

the poverty of the slums in a study of the possessions of the poor. He noted how

short a length of time possessions are kept.

Substantial proportions of people’s possessions

had been bought secondhand. Often, even beds had to be pawned in order to

provide more basic needs. The average ownership of a bed was only four years and

eight months. Jewelry was pawned more often, so little remained. Toys were few.

There were several articles of furniture considered essential: a bed, a

mattress, a table, a shelf for an altar and a set of shelves for dishes, a

chair, a wardrobe and a radio. The wardrobe was often a wedding gift from

husband to wife (I have observed this also, both in Manila’s slums and

Calcutta’s slums), and represented a relatively large investment. It was the

longest held piece of furniture.

Eleven of the fourteen families studied by Lewis

had kerosene or petroleum stoves. In the other three, cooking was done over a

brazier or earthenware hotplate.

This type of cooking is a common pattern in many

cultures. The poorest use wood fires (or dung in South Asia and the Middle

East) in earthen hearths or firepots of various kinds. Charcoal is a step up

from this. The next step up is the use of kerosene. In many countries the next

step up for those with jobs is to use a two-ring gas burner connected to a

small gas tank.

Nutrition of the poor

Another perspective on the absoluteness of

poverty is to consider the malnutrition in a community.

Malnutrition may be caused by bad hygiene and

health practices or by lack of food. Health services are generally better in

cities than in the rural areas, even for squatters. There is generally a good

supply of food in the city. Malnutrition in the slums is caused not by the lack

of food, but by the lack of finances and the nature of a new urban diet—a diet

without the traditional combinations developed in rural cultures through the

centuries to give a healthy balance of nutrients.

The problem becomes one of adaptation to new patterns of packaged city foods. The migrant squatter is thus affected by the kind of food, the quality of food and its quantity. Advertising has a further negative effect.12

Employment in the slums

While lack of housing may be the fundamental definition by the middle class of what are the squatter areas, the most important issue in the minds of the poor is not housing but the reason for their coming to the city—the possibility of finding a solution to their poverty in work.

Attractive financing, donated land, and subsidized transportation to and from relocation areas are insufficient incentives for many squatters to relocate out of the city. They will accept the land or house, and return to the city again to live as a squatter. They must be near their work. They cannot afford the time or money to travel long distances. The problem is that there is no work for many and inadequate work for others.

Non-employment

The squatters are largely unemployed or underemployed in terms of traditional definitions of work in a modern city. A study of one community in Manila showed the fathers of households as 20 percent unemployed (half of these because of physical disabilities), and 80 percent underemployed.13

The source of the problem lies in the slow growth of the modern sector relative to the population increases in the “traditional” sector. Employment opportunities do not expand and per capita income remains low.

There is employment within the squatter areas,

and the poor find employment within the city. But it is of a different kind than

that of the middle-class city. It is easiest to understand by perceiving the

city as a duality with two coexistent economic systems that are interlinked but

have different characteristics.

One way of analyzing the extent of unemployment

is to discover the length of time that people are out of work. For example,

while living in the dynamic context of Sao Paulo, I asked my friends, the

favelados with whom I stayed, how long it had taken them to find jobs when

they were unemployed. In general they were able to obtain work within about

four weeks. In the less buoyant context of Manila, it was not unusual for people

to wait one or two years between jobs. Unemployment maims the spirit, dulling

its ethics with an overarching anxiety, and generating the other evils of the

slums.

Kinds of work

Types of work generally include services, domestic activities, trades, artisans, small-scale businesses, hawkers, and self-employed generally categorized as unemployed.

Small-scale businesses are characterized by low capital and turnover, limited stocks, a small number of persons in each establishment, little space which is usually in a home, and dependence on credit as the mainstay of the business.

In certain cases, especially where demand is uncertain, the transformation of a family enterprise into a capitalist enterprise would lead to bankruptcy.

Hawkers are the lowest level in the commercial structure. Often they are not self-employed but part of micro-chains controlled by bosses.

Financial mechanisms of the squatter areas14

Some of the characteristics of a poor people’s economy have been analyzed. It is built around family enterprise and self-employment. There is limited capital investment. For example, the average number of loans to the informal sector in Calcutta in one program varied around one thousand rupees (or US$80). Outdated or traditional technologies are used. There are high profit margins, and many available jobs. Classical unemployment is unknown. There is a pattern of non-institutional credit, with cash being in constant demand, no advertising, and no bookkeeping. While good management facilitates larger profits, it is not essential for a business to survive. Obsolete transport powered by both animals and men is used, and poor quality equipment and recycled commodities are prevalent.

Cash Economics

The spread of monetary commerce makes squatter

areas cash economies. There are no checking accounts. Small denominations of

currency are necessary, but scarce. Storekeepers will bargain hard in order to

end the day with the types of currency that are least available. As the capital

is in circulation, little of it can be accumulated, so the poor remain poor.

Cash primes the credit pump and then keeps the

mechanism “lubricated” through its function as a means of payment.

The major obstacle to the acquisition of

capital, however, remains the need to pay accounts on fixed dates. The rules of

the upper circuit-banking sector are incompatible with those controlling the

lower circuit. People turn to more flexible wholesalers and moneylenders—the

middlemen.

Middlemen

With their access to bank credit, middlemen are an integral aspect in this economy playing a privileged and strategic linkage role. The middleman furnishes credit in goods or cash, operating as a wholesaler with connections to the upper circuit and the ability to store large quantities of stock. The poorer an individual, the more dependent he is on this middleman.

Credit

This is essential to entrepreneurs and consumers, but leads to an increased indebtedness at all levels. Thus usury becomes generalized. A lack of money supply in lower sector necessitates credit, increasing the rapidity of monetary circulation.

Credit for the poor consumer is possible through

this lower circuit trade. This trade also breaks up goods into small quantities

within the budget of the poor.

Bank accounts and entrepreneurial credit are

available to wholesalers and middlemen but not to artisans and small-scale

businesses. People involved in these small-scale activities cannot offer enough

guarantees, cannot pay bills on time, and would lose all if they defaulted.

Hence the banks turn to wholesalers, who then extend a flexible credit to the

smaller businesses, which is mutually advantageous. The loans are flexible. If

the poor cannot pay, debt may be extended. Neither party wishes to lose the

mutually advantageous relationship. To cover such loans, the further one goes

down the economic ladder, the shorter becomes the duration of the loan, and the

higher the risks and interest rates.

Effects of inflation

Deflation does not benefit workers. Inflation is no better, for it acts as a mechanism to exploit the poor, increasing prices faster than wages. But it increases employment in the lower circuit. And it benefits homeowners in the slums.

Comparing levels of poverty

These complexities in the nature of poverty, caused by or resulting in deprivation in several areas of life, make it difficult to compare poverty between cities.

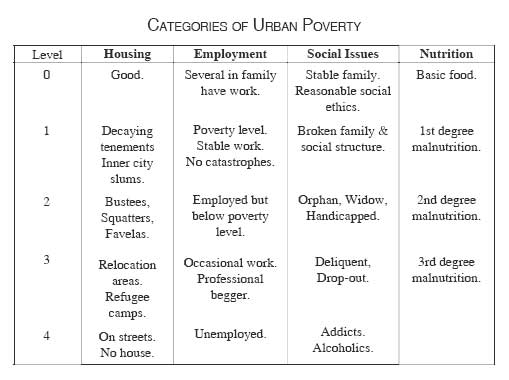

The chart on the previous page is an attempt to understand four of the above categories of poverty in any city. Any numbers of combinations from different columns are possible.

Any family could be classified on a scale that is the sum of the four variables at the different levels. For example: a bustee family in Calcutta that has a small industry and is stable would rate 2+0+0+1=3, while a dropout on the streets of L.A. may rate 4+4+4+1=13, even though he has more money in relative and real terms. Perhaps one should add in a measure of opportunity (a factor that could be defined by its relationship to economic growth rate of a city).

This kind of analysis, while it should not be allowed to consume inordinate amounts of time in excessive surveys, does give indications of which groups of poor may be more reachable, responsive and able to be discipled within the resources of the city and the mission. Each area of poverty must be addressed.

A study of 50 categories of poor in Calcutta

Calcutta provides a situation where all forms of

poverty and of response can be seen. The following are several groups of poor in

this city that require Christian response. The responses listed here are

responses to their poverty. If a church were to be planted among any one of

these groups, it would have to address these economic issues in the process of

its maturing and discipling of these poor. 1. Pavement-dwellers

There were officially 48,000 at the last census.

These 48,000 were found to be: permanent (45.6 %), migrants (such as those

intending to return home, 18.5 %), seasonal (24.1 %), regular visitors (for odd

jobs or business, 4.5 %), casual visitors (4.7 %), and others (2.6 %). 66.5

percent cook on the pavement. 36.5 percent eat once a ![]() day,

52.1 percent eat twice a day.15

day,

52.1 percent eat twice a day.15

These 48,000 may be also considered in terms of their occupations: beggars/on charity (22.0 %), casual day-laborers (23.4 %), thelawala or hand-cart puller (6.5 %), rickshawala or rickshaw puller (7.3 %), hawkers (3.1 %), paper/ragpickers (4.8 %), regular day laborers (8.6 %), vegetable sellers (3.6 %), maid-servants (4.2 %), and others (16.5 %).16

Further classification may be made in terms of deviant behavior, such as: delinquents, criminals, prostitutes and street gangs; or of special cases: street children (orphans, deserted or runaways), the blind, lame, deaf, dumb, leprosy patients, older widows and deserted women.

Responses to this diversity of needs may include emergency relief (such as food, medicine or clothing), short-term rehabilitation or long-term rehabilitation. Short-term rehabilitation focuses on employment, because poor people need work more urgently than they need accommodation, or anything else. Short-term rehabilitation programs may thus provide specialized training to upgrade skills, vocational and non-formal education to street children, and perhaps shelters for rickshawalas, thelawalas, and day-laborers. Sometimes a local social club can become a starting point to assist people with solutions to their problems of survival. Long-term rehabilitation in Calcutta and the region surrounding the city includes the development of rural agriculture, the establishment of cottage industries, and the formation of a government planning committee to focus on this problem by creating any necessary legislation and by influencing public opinion.

2. Refugee colonies

These embrace a population of about 500,000 (CMDA, 1981), and include government-sponsored colonies, squatter colonies and private colonies. The responses should be similar to those of the bustees below, with the proviso that unemployment is greater in the refugee colonies.

3. Squatter areas and bustees

The residents in squatter areas and bustees are either of a permanent type (with potential land rights or legal tenancy), or of a temporary nature (with no land rights or tenancy possible). They may live on unneeded government land, on government land needed for development, on private land with tenancy contracts, or on private land that they illegally occupy. In any of the above cases, the responses would be the same:

a. Government legislation to secure land rights;

b. Slum upgrading, sites and services, environmental development;

c. Development of small-scale and cooperative industries using low-interest loans;

d. Development of community organizations to enable the people to tackle their various problems;

e. Vocational training; and

f. Preventative medical work.

4.

Overcrowded downtown multistoried

housing

Responses to this situation would

probably include re-housing the people in middle-class developments in suburban

areas or inner-city redevelopment.

5. Oppressed workers and servants

To help oppressed workers, trade unions need to be developed, Christian businessmen and professionals encouraged to get involved, and forums planned to consider issues of justice for workers.

6. Women in oppressed roles

Responses could include a publicity campaign for change of values and the focusing of women’s organizations on specific issues.

7. Oppressed minority groups

Among oppressed minority groups are Muslims, the Anglo community, lower-caste people, certain traditional {but no longer useful) trades groups, the disabled, the aged, and widows. For these, an adequate response would include one or more of the following: permanent welfare programs, specialized schools, retraining in useful trades or professions, and psychological reorientation to God’s perspective on their status.

Notes

1.Moorehouse, Geoffrey, Calcutta, Penguin Books, 1984.

2.Ganguly, Tapash, “Pains of an Obese City,” The Week, Nov 17-23, 1985.

3.Calcutta Metropolitan Planning Organization, A Report on the Survey of 10,000 Pavement Dwellers in Calcutta: Under the Shadow of the Metropolis—they are citizens too, Sudhendu Muukherjee, ed., 1973.

4.Grigg, Viv, Companion to the Poor, Monrovia, California: MARC, 1990.

5.Moorehouse, op. cit.

6.Wilson, Samuel, Unreached Peoples 1982, Monrovia, California: MARC, World Vision International, 1982.

7.Pentecost, Edward C., Reaching the Unreached, Fuller School of World Missions thesis, Pasadena, 1979.

8.Paredes, Tito, ed., PROMIES Directorio Evangelico: Lima, Callao y Balnearios, Concilio Nacional Evangelico del Peru, 1986.

9.Mar, Matos, Desborde Popular y Crisis del Estado, Institute de Estudios Peruanos, 1986.

10.Abrams, C, Man’s Struggle for Shelter in an Urbanizing World, Boston: MIT Press, 1964.

11.Lewis, Oscar, “The Possessions of the Poor,” Cities: Their Origin, Growth and Human Impact, Readings from Scientific American, San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Co, 1973.

12.Arnauld, Jacques, “Urban Nutrition: Motor or Brake for Rural Development? The Latin American Case.” Ceres, Mar–Apr 1983.

13.Decaestekker, Donald Denise, Impoverished Filipino Families, Manila: UST, 1978.

14.This section based on Santos, Milton, The Shared Space, tr. from Portuguese by Chris Gerry, London and New York: Methuen, 1979.

15.Calcutta Metropolitan Planning Organization, A Report on the Survey of 10,000 Pavement Dwellers in Calcutta: Under the Shadow of the Metropolis—they are citizens too, Sudhendu Muukherjee, ed., 1973.

16.Ibid, table 8.

© Viv Grigg & Urban Leadership Foundationand other materials © by various contributors & Urban Leadership Foundation, for The Encarnacao Training Commission. Last modified: July 2010Previous Page |