Home Course Admin Foundations Spirit Centred Spirituality Evangelical Spirituality Contextual Spirituality Classic Urban Spirituality Slum Spirituality Incarnational Spirituality Indigenous Spirituality Self Analysis Family Life Readings

Group Structures for Squatter Churches

Reference: Grigg, V. (2005). Cry of the Urban Poor. GA, USA: Authentic Media in partnership with World Vision.

IN JOHN 17, JESUS REFLECTS IN PRAYER about the work he has accomplished on earth. It is his final prayer, and final words usually contain central convictions. He prays for those whom God the Father has given from the world. He does not now pray for the world, but for this group of twelve.

Here he defines the goals of group discipling. He

has manifested the Father. He has taught the Word in such a way that the

disciples have obeyed. He has protected them, leaving them in the world, but

sanctifying them in It. He has sent them forth and has modeled for them how they

should minister. He prays for their spiritual unity.

These men are central elements In his ministry.

Through these men he sees the world. He has formed a new sociological

paradigm—a new small-group structure and a new pattern for birthing a movement.

Based on these building blocks we can develop patterns for forming churches.

Three structures for the poor

I have found that there are three patterns of church structure that serve the urban poor:

1. Multiplication of squatter churches

The pattern prevalent in the ministry of Latin American churches among the poor is a multiplication in geographically-defined squatter areas and slums through an incarnational, small-group-movement approach. This model I have defined for missionaries in a number of writings.

These local slum congregations speak the heart language of the people, have local eldership, but are linked to other slum churches or vertically dependent on a middle-class church. They enable the slum dweller to feel at home in a slum culture, but have some ties to the outside middle-class city structures.

Many slum residents, while connected to the city, rarely venture into that city. A squatter may be a city-dweller in his or her own mind, but he or she is not necessarily identified with the structures of the middle-class city. The kind of church we have referred to in the preceding paragraphs is the only one that is likely to be appropriate for such a squatter.

Some traditions talk of a return to the New Testament church patterns. In the slums, however, first century patterns are inappropriate. There are no villas for house churches to meet in, so a local church building must be built (frequently known in Latin America as a templo, or “temple”). In third-world slum areas, there are no godly Jewish converts with stable families and depth in the Scriptures who can immediately step forward to lead new congregations. In the slums, heavy dependence upon the pastor for leadership may continue for some years. There is no concept of a synagogue to clarify what a church should look like, causing the poor to import middle-class Western or Catholic styles of church.

2. A gang-structured discipling web

A gang-like discipling movement works among specialized groups such as addicts, alcoholics etc. It may have a structure similar to a drug gang, but it is built around the authority of discipling relationships that emanate from a strong, central, intensive, discipling, charismatic figure.

Alcoholics Anonymous, jail ministries and work among drug addicts, such as those of Jackie Pullinger or Teen Challenge, are among the current models of these city-wide ministries among the poor. They are not churches, yet churches may result in the squatter areas from such effective discipling.

3. A central-city, front-led superchurch

In some urban areas, there are great inner-city, charismatic celebrations held in the trade language of the city (in Asia, this is often English). The squatter can be linked to a middle-class city structure through these large-scale celebrations, yet at the same time attend smaller cell groups among other squatter and slum people that are holistic and incarnational. The middle-class fellowship has sufficient income to underwrite an indigenous pattern of supporting these smaller churches among the poor.

A woman transformed!

She had served as an assistant to the wife of a deposed : dictator, and was used to getting things done. Now she had just completed the foundation for a new church in the slums.

She had been touched by God in a big, upper-middle class, charismatic fellowship that met in a shopping mall—at times there had been 4000 attending. The leaders had sent her to this garbage dump as she responded to God’s call. Every day she traveled an hour and a half to reach the people who lived at the dump. Hers was one of five new outreaches to the poor from this particular fellowship.

This approach, however, cannot even be considered where the poor speak a different language from that of the rich and middle class. John Maust makes an interesting observation:

My informal investigations turned up only two Quechua-language evangelical congregations in all of Lima. More Quechua churches seem a pressing need, considering the influx of thousands of people who grew up speaking one of the Quechua dialects as their mother tongue. Statistics say that 30 percent of the 18 million Peruvians speak only Quechua. These people will never go to a superchurch. And if they did, they couldn’t invite their neighbors, who probably will never be able to afford the bus fare. Incarnation in this situation is our only option.

Four seasons of growth

Just as there are normal patterns of personal spiritual growth, church growth of poor peoples’ churches also follows regular patterns. Some steps must precede others. Some areas need to grow before others can develop. 2 Corinthians 3:18 tells us:

And we who with unveiled faces all reflect the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his likeness with ever increasing glory, which comes from the Lord who is Spirit.

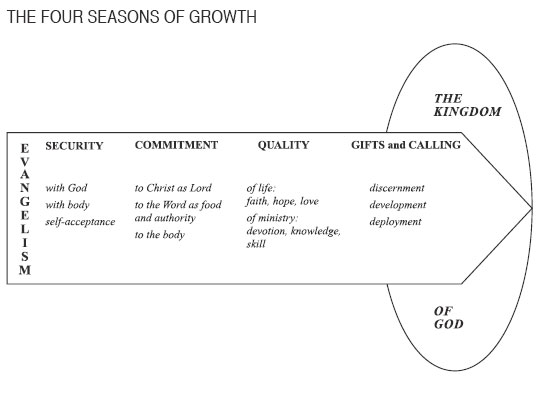

The chart on page 168 came from Gene Tabor and the Philippine leadership of REACH, a chart whose initial framework is known as the FOCUS Chart. Based on experience among the poor, this chart illustrates four distinct phases in the development of the life of a disciple and of fellowships of disciples as they move step-by-step to maturity.

Whereas most methods are most useful in the culture where they originate, the principles in the FOCUS chart’s analysis of ministry appear to be universal. Starting with these principles, we can determine methodologies in each culture or sub-culture. The principles are based on processes a group of believers goes through when the Holy Spirit is working in a healthy manner in them. Beware, however—the processes are not the Holy Spirit. They are only the evidence of his indefinable and infinitely varied work.

The idea of a growth-oriented theology is implied in 1 John 2:12-14, where John talks of three phases of growth and defines some qualities of believers at each phase. From these, we may derive some ideas of what to focus on at any given season of growth.

I write to you, dear children, because your sins have been forgiven on account of his name. I write to you fathers, because you have known him who is from the beginning. I write to you young men, because you have overcome the evil one. I write to you dear children, because you have known the Father. I write to you fathers, because you have known him who is from the beginning. I write to you, young men, because you are strong, and the word of God lives in you, and you have overcome the evil one.

We can define the characteristics of each phase described by John. The knowledge of God mentioned for both children and fathers in the Greek text is the same word. In practice, however, we realize that John is talking to children who have first experienced knowing God, and to fathers with a deep intimate relationship with God. We may also infer that the spiritual fathers have spiritual children.

1 JOHN 2:12–14

Children young Men Fathers

• Know Father • Strong • Spiritual children

• Sins forgiven • Word abides in

• Companionship

them with Father

• Overcome evil one

While John defines three phases of the Christian

life, in practice we have found there are four distinct phases, as the

development of spiritual fathers is not a simple process. Before these four

phases, we should remember that there is a “zero phase”—evangelism.

By looking at the characteristics above, we find a

single word that defines a focus of ministry at each of four phases. (Notice,

however, that this is a merely a focus—we do all things at all phases, but we

concentrate on some at certain times). Many American books on disciple-making

define discipleship by specifying goals for each phase. In Asia, and among the

poor, this is a threatening and counter-productive approach, because it runs

against the holistic cultural values of traditional societies. This chart is

useful in Asia because of its focus on an atmosphere for ministry rather than on

goals for ministry at each phase.

First season: security

Forgiveness of sins and knowledge of the Father indicate a focus on assurance and security. For those with difficulties in their relationships with their human fathers, there has to be healing if they are to love God. Some have difficulty in relating to others. They need a warm, loving group with lots of fun and fellowship, where fears are put to rest and new skills in relating can be learned.

During this phase, a leader will concentrate on teaching those aspects of the nature of God that lead to security—forgiveness, love, faithfulness. What are known as the basics of Christian growth are also important—how to become familiar with the Bible, how to have a daily quiet time, how to read the Bible, how to pray

Togetherness and a sense of family and friendship are factors in all these activities, including many fun activities such as outings, sports, and meals together. It is also a time of fruitfulness for a new Christian, for he or she has many friends who may not believe in Jesus Christ. An older Christian also needs to be present, for while the new Christian can stir interest, he or she may not know how fully to communicate the gospel.

Charismatic worship is useful at this stage because it creates an environment where the presence of a loving Father God is seen and felt and preached through word and song.

Healing of major past hurts is also an aspect of

growth at this time. The Scriptures say little about the psychology that is

popular in present evangelicalism concerning inner healing. The central element

in the Scriptures is forgiveness for those who oppress, and confession to those

we have offended. Healthy patterns of confession and forgiveness need to be

built into a fellowship as a basis for the continuing work of the Holy Spirit.

Self-acceptance is important during this phase.

People tend to accept themselves on the basis of good looks, achievements or

status. God has a different basis of acceptance—his forgiveness on the cross

and his fatherhood. If these areas do not become strong during the early

Christian life, there is insufficient basis to handle later pressures of

ministry.

Second season: commitment

Young people are strong. It is the younger

generations who participates in sports and go to war. There is a level of

commitment in youth that develops and can be encouraged.

Commitment to each other at this phase differs

from that in the first phase. For people from broken families, a commitment to

the family of God is a major undertaking. The first phase of growth in the

family of God is one of fun and fellowship. Commitment to the Body during this

second phase is a commitment that is tested. After realizing the failings of

other members, after perhaps having some conflict with another member, then each

new Christian faces the challenge of continuing to love. There needs to be a

regular evaluation of the issues of forgiveness and restitution in group

relationships—usually at the communion table.

I have used a phrase—“Commitments 1,2,3,”—as a

basis for building core teams during this period of ministry. Commitment to the

Lord comes first, to the Body second, and to ministry third. If there are

relational problems within the team, they will take priority over the external

ministry of the team. The external ministry will always be there—there will

always be needs, and the Lord promises that we will bear fruit. But relational

problems are an immediate block to his working in and through us.

There are also issues of commitment to the

Lordship of Christ. The discipler has to help people evaluate that Lordship in

each area of their lives step by step. Will Christ be Lord in the areas of

finances, family, marriage, missions, reputation and honesty? Any of these

things may come under testing during this phase of growth.

This is a time also of battle—of spiritual

warfare. Young Christians need a commitment to the Word of God as the weapon of

war. The Word also is their food and authority for life. Many may have an

academic acceptance of the Word of God as authority. But discipling involves

more than that—it involves helping new believers to turn to the Word for

practical instruction on matters of family, finances, relationships and so on.

There needs to be training, as well, in the proclamation of the gospel, and in

spiritual warfare.

During this phase there may be many long,

late-night talks with older, mature Christians as the younger Christian works

through issues. Small groups are a good setting for this. Too-close individual

discipling relationships with a high-powered older Christian may be threatening.

But during this second phase, long talks are inevitable and probably necessary

as the new Christian works through many issues.

Training seminars are very effective during this phase of growth. Over a period of time, believers will have evangelized those who are responsive among their friends. The non-responsive will have drawn away from them, leaving them thus to find their friends increasingly in the church. This is healthy. But as they grow in commitment to the Great Commission they need help to start re-establishing relationships with non-Christians, and training in how to share their faith effectively.

It is good to encourage new believers to form evangelistic teams during this phase. Towards the end of this period one senses that fruit is about to come. It is the sign that someone has truly become not just a follower-disciple, but a faithful, tested disciple of Christ.

Third season: quality

The discipler encourages the fruit of character

and ministry to emerge through teamwork and by bringing the new believer into a

close relationship and the home life of the discipler. Working through the

Beatitudes is a good pedagogical tool for relating the Word of God to character

issues during this phase.

This is also a period where deeper levels of

commitment, skills and a heart for ministry can be developed. Supervised

ministry experiences are needed, with increasing levels of responsibility, and

other occasions where the leader works with the growing Christian.

All believers should be developed through this phase into a maturity in Christ. They should be given basic ministry skills for leading another to Christ, holding a small Bible study and personal discipling.

Fourth season: gifts and calling

Finally comes a phase where intimate knowledge of

God and his calling makes it possible for specific gifts to be discerned and

developed. Now the person may be deployed in a place of ministry where his or

her gifts will be fully utilized. Some are called to develop as leaders, and

energy must be concentrated on their lives. Others need help finding their

place in the Body so they are fulfilled in their gifts and roles.

During this phase, greater degrees of freedom

occur, as leaders spin off into new ministries of their own. Others are better

gifted to remain working as co-laborers with the ministry leader.

Integration

The usefulness of such a chart is that we may

enter any group, discern at what level of growth they are, and minister to them

at the appropriate level.

The first and last phases are ones with a great

deal of freedom and variety for the people involved. The middle two phases, on

the other hand, are phases of tightly committed training, where the ministry

leader expects high levels of commitment and exercises a significant level of

direction and authority.

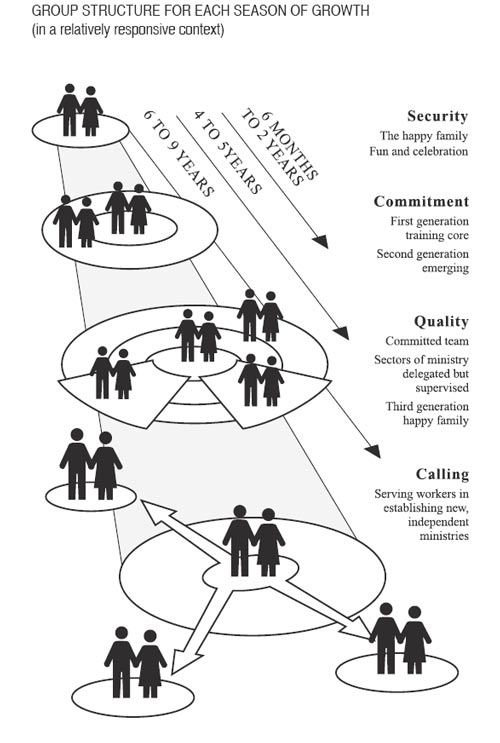

The time frame for each phase varies with the individuals, experiences and cultures. Generally, the first phase may take from six months to two years, the second from one to two years, the third will normally be completed by the fifth year of growth of a new convert.

Discussion with many ministry leaders indicates

that it takes eight to nine years to train a spiritual father or mother. Indeed,

in this final phase, not all are called to be spiritual fathers or mothers.

There are many other gifts that need developing. The length of time to produce a

spiritual father or mother is apparently independent of the structure of

training they go through—be it in a Bible college, or through a lay leadership

movement—it still takes about the same length of time.

The charismatic dimensions of deliverance from the

demonic, the exercise of spiritual gifts and the healing of emotional wounds

are an important element in the provision of security in the first phase. They

are generally overemphasized in charismatic circles, however, simply because

the new believer’s character problems often limits the extent to which the

Spirit can use a person. At the end of the third phase, one sees extensive

impact of the Spirit and fruitfulness in ministry, and it is here that the

development of spiritual gifts enters a deeper realization.

Many young Christians seek the exercise of dramatic gifts and are disappointed because they seem unsuccessful. It would be far better to give themselves to growing in knowledge of the Word and of the Lord. In time, fruit will develop from a life of abiding in Christ, and gifts will become evident. Similarly, many fundamentalist evangelistic and discipling programs put pressure on people to produce fruit in evangelism. While evangelistic skills need to be learned, the Scriptures teach that fruit is the result of abiding in Christ, in his Word and in prayer. It is not the result of increased pressure and techniques (John 15:5-7).

Security precedes fatherhood

He was a new missionary who had never dealt with the issues of security during his early training. The trauma of his parents’ death, experienced as a teenager, had severely damaged his ability to understand fatherhood.

He was now trying to function as a ministry leader (phase four), and the lack of security was crippling his capacity to be a spiritual father. The flock was reacting to this lack. He would try to compensate by developing new programs. But because he lacked the fatherly concern needed to execute them, the programs failed.

He would spend hours staring into space or walking alone, seeking release from the emotions he felt. Guilt increased. Eventually his ministry was paralyzed. Then God began to minister his fatherhood to those early hurts . . ..

Each season is a prerequisite to the next.

A word of warning is called for here. The four seasons chart is human wisdom based on the experience of application of the Scriptures to Christian growth. It is a focus for that growth’s different phases, but it is not the infallible word of God.

Place of personal discipling

Many Western discipleship models emphasize personal or one-to-one discipling. This works well among individualistically-oriented peoples, but not in most of the world. A discipler’s task is to create the environment of growth at each point—not to do everything alone. The group dynamic is crucial. Personal discipling patterns need to be there, but should not be overly emphasized, particularly in group-oriented cultures.

The discipler needs to form a healthy relationship with the young Christian and to be available at critical times, but he or she should not become overly intensive in discipling, as this can be very intimidating for anyone. The members of Christ’s body, his church, minister to each other. The discipler’s task is to create the environment where this can happen.

Apostolic “thrust” and pastoral concerns

In the early phases of its development, the church will tend to manifest more of an evangelistic, apostolic style. In later stages, more pastoral issues will come to the forefront. Correspondingly, in earlier phases we would expect more power encounters. In later phases we would expect to see more emphasis on economic and social development. An overemphasis on power evangelism may lock young churches into a pattern of continual turnover of new converts without long-term pastoral care. The church planter’s task requires maintaining a fine balance between these poles.

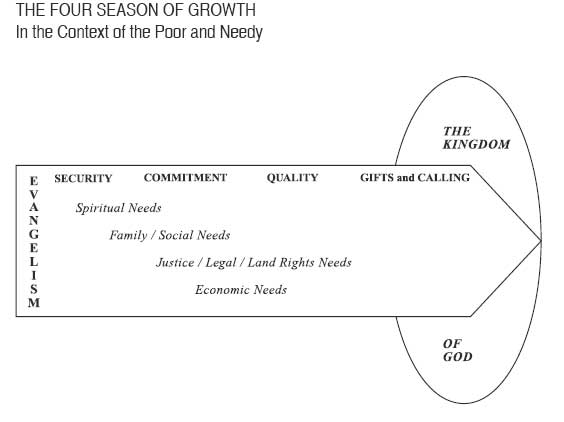

Holistic poor peoples’ churches

God’s intentions are for maturity in us as individuals, in churches and in the world. Paul sought to present every individual “mature in Christ” (Col 1:28, 29). We are to develop the church to be “without spot or blemish” (Eph 5:27). We are to pray and work for the world so that “thy kingdom [may] come” (Matt 6:10). The gospel deals with all these areas, for “all things hold together in Him” (Col 1:17). The gospel embraces all of life and creation.

Thus we may re-diagram the four seasons chart to consider these four areas at each of the four seasons. (See the diagram on the below titled “The Four Seasons of Growth in the Context of the Poor and Needy.”)

Physical need and spiritual growth

The four seasons of growth follow a pattern observed by psychologists in the levels of development in children as well as in cultures. In 1954, Maslow discerned a pattern which defined the primary needs of mankind at a survival level.2 If these are met, then people pay attention to needs at a security level. If most of these are met, people then have enough energy to pay attention to their needs for a sense of achievement. The highest level Maslow defines is self-actualization, a term that Christians have some difficulty relating to because of its linkage to New Age thinking. Perhaps we would define it as a level of maturity, of total dependence upon God.

In Israel’s exodus from Egypt, the Lord’s task was to change the character of a stubborn, stiff-necked, slave-mentality people. How does enslaved person become a mature people? Our task among the poor is not dissimilar to the process followed by Israel during the exodus.

Similarly, when Jesus began his ministry, he found some secure, achievement-oriented businessmen, some government officials, and a few revolutionaries. He structured a context where these four levels of need could be met for team members. In doing this, he gave leadership to a movement that spread mainly among those who were lacking at the levels of security and survival. His core team members were not destitute. They were not failures.

Survival

Our primary level of need is to survive. If we are unable to meet basic needs for food, clothing and housing, our whole psyche concentrates on finding solutions to this problem.

For example, the Nazis succeeded in cutting down the food level of people in concentration camps to 700 or 800 calories a day (men normally need 3,000 and women need 2,400). There were no riots, and no sexual problems between men and women. All their attention was focused on getting the next meal. It is the same with the destitute poor.

God, in the desert, met the survival and security needs of the Israelites so they no longer had to focus all their attention on these issues. So too, Jesus provided for the twelve who traveled with him through the support he generated from his ministry,

John Wesley was saddened by his inability to reach the poorest of the poor. William Booth took up the challenge, developed an economic base, and began to see fruit from evangelization and discipling.

Security

Ruth Benedict, an early anthropologist once

studying an island tribe, asked the question, “Why were the island children so

insecure?” The answer appeared to be related to a lack of identity. Children

were cared for by a multitude of older people. They did not know which of the

adult women was their biological mother. The result—an unmet security need and

a static society. Because all of their energy was focused on meeting this

security need, there was no achievement. Security always comes before

achievement.

Among the poor, we must work to enable the

potential leaders of the fellowship to arrive at economic self-sufficiency

(meeting survival needs). We must develop healthy group dynamics for the family

of God so that their security needs are taken care of.

A movement among the poor must develop a clear

structure with various levels of leadership and fellowship. The nature of the

structure may vary, but consistency and clarity are critical. To a certain

degree, the people must know what to expect. This is why many non-incarnational

Western missions end up with a modest rate of church growth, even though they

do not develop indigenous patterns. The structures they produce, while not easy

for the national people to work within, are stable, and hence produce some

degree of security.

One structural pattern, for example, that tends to

recur among peasant cultures, and hence among slum churches, is the choir. In

Brazil, where choirs abound, one sometimes even sees dueling choirs in the same

church—the ladies’ choir outdoing the youth choir, or the guest choir

serenading the local church choir. These choirs provide a secure context of

growth for new believers.

Why Is there a need for such security? People

cannot move to a place of subjection to Christ as Lord of all If they are not

first secure in their relationship with God. How do you trust him if you are not

sure he is faithful? How do you trust him to provide until you have experienced

his provident sovereignty?

If these first two levels are met, people have

enough psychological energy to develop at the next level.

Achievement

Jesus met his disciples’ survival and security

needs. Then, to meet their achievement needs he gave them the truth and sent

them out to minister. We need to encourage new churches to develop financial

structures that free leaders from financial restraints in order to devote

themselves to ministry.

John Wesley never would have succeeded In his

ministry If he had not received a regular stipend from the church. This met his

survival needs. Working from this base, he could freely give himself to high

levels of achievement.

Maturity

Culture in any society normally has been advanced

by the leisure class. In the same way, theological and new ministry concepts

generally come from those who have the time for meditation, creative study and

thinking. The people who engage in these activities are not dependent on

achievement for their self-identity or self-esteem. They achieve not to meet

needs, but instead for the joy of achieving. People at this level constantly

seek to create and to understand. While they may relate well to others, they

are not controlled by emotional needs in relationships.

The overall leadership of movements among the poor

will probably come not from the poor themselves, because few are able to develop

their gifts to this level, but from the educated elite who have had time to

attain the required level of maturity. To be effective, these leaders must

choose lifestyles of voluntary poverty.

The four categories of growth that we have

mentioned parallel those of the four seasons chart, but add the important

factor of meeting survival needs as a basic step for enabling the poor to grow

to full maturity in Christ.

From fighter to leader

He was one of the first to come to know the Lord in the community. He hungered after God, eager to learn all he could be taught. At first he oscillated back and forth between his old drinking friends and the newly-discovered prayer meetings. He did not want to lose friendships.

The pastor remained patient with him, talking with him about the testimony involved, and helping him to apologize to the other believers whenever he got drunk. One morning, after a drunken night, he talked long with the pastor and made a decision to stop drinking.

His hunger for God and the Word remained. He began preaching around the barrio, and many were affected by his new testimony. One night some old enemies turned up outside his house. He tried to talk to them with grace, but the enmity ran hard. They drew knives. He and his father ran into the house and returned with their machetes. They chased the men . . ..

There was much counseling. Again there was public repentance. In the counseling it became obvious that the fight had occurred under the influence of evil spirits. Prayers were offered in the house and for the new Christian. His father gave his heart to the Lord.

His desire for the Lord continued to grow. The pastor remained patient. The new convert started some new Bible studies. People started coming to the Lord.

One day, under the ministry of the Holy Spirit, the Lord showed him many past scenes and brought balm, into each one. The fighter was being transformed. With a new-found anointing from God, the Bible studies grew. But sadly so did the tension between the new believer and the pastor who had so nurtured him . . .

The last time we talked, he himself had become a pastor. Now he worked in unity with his former pastor. The story is not finished, for God is not yet finished . . .

Notes

1. Maust, John, Cities of Change, Latin American Mission, 1984.

2. Maslow, Abraham, Motivation and Personality, New York: Harper and Row, 1987.