Constructing a theology of mission for the city

Charles Van Engen

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you, how often I have longed to gather your children

together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing!

Look, your house is left to you desolate. I tell you, you will not see me again until you say, "Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord." Luke

13:34-35

WERE THESE WORDS of Jesus a sigh of deep pathos, a cry of excruciating agony, or

an exasperated pronouncement of judgment? Matthew (23:37-39) places them after

the triumphal entry, closely joined to the seven woes pronounced on the leaders of the Jews,1 and an integral part of Matthew's

long discourse of eschatological issues concerning the end of the age. In Luke (13:34-35), the nearly identical words of Jesus appear while he is on his way to Jerusalem, before his triumphal entry, and placed alongside Jesus' conflict with Herod, who is plotting to kill Jesus.

Whether viewed through the Matthean paradigm or the Lukan, 2 we could take Jesus' cry, "0 Jerusalem, Jerusalem!" as a profound statement by Jesus concerning God's mission in the city.3 It makes clear God's loving commitment to be involved with, and related to, the city.

God's initiative in sending mission messengers to the city is evident. The Gospels mention Jerusalem's mixed (mostly negative) response to God's love. But the dominant image is one of pained, loving, salvific tenderness: a hen clucking furiously to gather her wayward chicks under her wings.

Although Jerusalem kills the prophets, God does not flee from, or give up on, Jerusalem. Instead, God sends his Son, who comes as King David's descendant, who comes "in the name of the Lord," who comes riding on a donkey on his way to the cross and the empty tomb-events that occur in the midst of, and for the sake of, Jerusalem.

In fact, we may view Jesus' entire ministry from the perspective of his encounter with Jerusalem. These words of Jesus mayor may not imply that he knew of the coming destruction of the temple in A.D. 70.

Yet the way both Matthew and Luke structure the text assures us that ultimately, through his death and resurrection, Jesus offers redemption and transformation of the old Jerusalem into the new City of God. This is an eschatological reality that John would later refer to in Revelation 21. True to God's form of response throughout the history of Israel, there is always grace in the midst of judgment; in the end, there is a rewriting of the story of Jerusalem.

As Roger Greenway says,

The last chapter in the Jerusalem story awaits the future. . . . She is called the Holy City and her Bride-groom is the Lamb. Life in the

new Jerusalem is peaceful. There are no tears, nor causes for them. Death and mourning are gone, and so are pain and suffering. Best of all, in this city God in Christ dwells forever with his people in perfect relationship. Grace has triumphed and shalom is established (1992:10-11).

I

When I hear those words of Jesus about Jerusalem, I hear the deep pain of an urban missionary. It also seems to me Jesus offers some profound theological truths that are simultaneously historical, contextual, relational, and missio- logical. Is it not possible that these words represent for Jesus what today we would call a "theology of mission for the city"?

As was noted at the start, this book is the result of a doctoral seminar that

met for forty weeks at Fuller Seminary's School of World Mission to search together for a way to construct a theology of mission for the city. During those months together, we found ourselves returning repeatedly to three basic questions:

1. Why construct a theology of mission for the city?

2. What is a theology of mission for the city?

3. How may we construct a theology of mission for the

city?

Because it is a preliminary set of reflections, the authors do not mean for this

book to offer the last word on this subject. Instead, we wanted to share with others the methodology

and content we discovered through our time together. In this chapter, I want to

give a brief summary of the methodology we followed, so that the reader can see how the methodology worked itself out in the particular stories, con- texts, reflections, and missiological directions offered by each author in the preceding chapters.

This volume intends to make a contribution to urban missiology, particularly in the arena of method of theology of mission, and considering the unique complexity of urban missiology. In the sixteen months we were together, the seminar group began to shape a methodology that begins on the sidewalks and streets of the

city, closely mirroring the way urban missionaries think about mission in the city.

Standing in the city, we began to build a holistic approach that centered on an integrating idea or theme in the midst of the complex multiplicity of urban factors. So the method is very simple, because it begins with a story, but it also takes seriously the complexity of doing theology as related to urban missiology. It is at once practical and theological, relational and reflective, macro-oriented and micro- conscious. In other words, we sought to do for urban mission something akin to what Ray Anderson advocated when he wrote,

Mission theology is the praxis of Jesus Christ through the presence of the Holy Spirit reaching out to the church through the arms of those whose humanity needs healing and whose hearts need hope. . . . If mission theology is to be integrated with church theology, let there be an authentic orthopraxy,

let it dare to submit its concerns and its agenda for the healing and hope of humanity to the One who is the Advocate, the Leitourgos, and the Redeemer of all humanity. . . . If there be an authentic church, let it be found where Christ has his praxis and his pathos-let it pay the price of its orthodoxy in its true ministry and so be empowered by Christ himself (1991:126).

This book is a small step. It seeks to explore how we might create what Ian Bunting, an urban missionary for more than thirty years in northern England's urban areas, called for: "an integrated method of training [urban missionaries]

which can truly be described as global in scope, mission-oriented" and thoroughly contextual." Especially important here is the search for a correlation of reflection with action, of values with programs, of theology and practice.

Ian Bunting comments,

While there is general agreement on a method of learning theology which involves

seeing, judging and acting, there is no such agreement about the way to

correlate theology and practice. There is, in fact, a sharp disagreement between those who look for more theoretical or systematic correlations (often the trainers in

universities, colleges, and courses) and those who pursue more practical theological correlations (normally to he found in urban training centers and institutes). The issue is as much about where we learn our theology as how we go about it. There is not much evidence that this divide between the academic and the practical has

been bridged by more than a few. . .

(1992:25).

WHY CONSTRUCT A THEOLOGY OF MISSION FOR THE CITY?

As the reader can see from the preceding chapters, the

seminar group represented a great deal of diversity on many

fronts. Yet almost from the first day we found a common convic1tion that became increasingly significant to us. We were at

all looking for ways we might better build on, and interaction with, the literature and programs we knew of that dealt \with urban missiology. Although impressed by the quantity of literature in the last twenty year~ written by those .who reflect about issues of urban mission,4 we remained restless to find new ways to integrate those insights with our theology and missiology.

It seems that especially in urban missiology, people have found it difficult to

deal with the whole system of the city. 0I1l the one hand, there are those

involved in micro-ministry who deal with individuals and their needs in the city- but they are often burning out in the process, in part because they are not dealing with the entire system. Some members of our seminar fell into that category.

On the other hand, there are those who spend. much energy doing macro-studies in

sociology, anthropology, economics, ethnicity, politics, and religion in the

city-but they seldom seem to get down to the level of the streets and the people

of the city. Their recommendations for concrete action seem weak, and their

activism mostly dulled by the vastness of their scope of investigation. The

staggering complexity of an urban metroplex like Los Angeles makes it nearly impossible for students of the macro-structures to convert their findings into specific, timely, compassionate, personal ministry.

Then, too, we found that many authors were caught up in one agenda or another. Community organization theory and practice seemed to need further reflection and interaction with the church in the city, an emphasis that Robert Linthicum has also called

for.5 On the other hand, as William Pannell points out, too much of mass evangelism has been blind to the city's systemic issues and has seldom sought the more radical, holistic transformation of the cities in which its evangelistic enterprises occur (Pannell 1992:6-22).

John McKnight highlighted this tension. "When I'm around church people," he says,

I always check whether they are misled by the modem secular vision. Have they substituted the vision of ser- vice for the only thing that will make people whole-- community? Are they service peddlers or community builders? Peddling services is unchristian- even if you're

hell-bent on helping people. Peddling services instead of building communities is the one way you can be sure not to help. . . . Service systems teach people that their value lies in their deficiencies. They

are

built on "inadequacies" called illiteracy, visual deficit, and teenage pregnancy. But communities are built on the capacities of drop-out, illiterate, bad-scene, teenage- pregnant, battered women. . . . If the church is about community-not service--it's about capacity not deficiency (1989:38,40).

There is a growing interest in planting and growing house churches in the city,6 yet too few of those have any missional intention to be God's agents for transforming the city itself.

Although generalizations like these are dangerous, our overall shared impression pulled us in two directions. At one end of the spectrum, we knew of many social service agencies "doing for" people with little regard for the city's systems (much less for gathering people into worshiping congregations).

At the other end, we also were aware of many evangelistic, church-planting efforts that did not deal with the entire scope of evil in the city. We kept seeing activists who seldom stopped to do the broader reflection, and reflective investigators who did not often get around to doing any- thing to change the reality of the city they were studying.

Meanwhile, the churches in the city (including ones where seminar participants are actively involved) continue to struggle to find how to be viable missional communities of faith in the city. For the church of Jesus Christ, life and ministry in the city involves living in profound tensions.

The church is not a social agency-but is of social significance in the city. The church is not city government-but God called it to announce and live out his kingdom in all its political significance. The church is not a bank-but is an economic force in the city and must seek the city's economic welfare. The church is not a school-but God called it to educate the people of the city concerning the gospel of love, justice, and social transformation. The church is not a family-but is the family of God, called to be a neighbor to all those whom God loves. The church is not a building-,-but needs buildings and owns buildings to carry out its ministry. The church is not exclusive, not better, not unique-but God specially called it to be different in the way it serves the city. The church is not an institution-but needs institutional structures to effect changes in

the lives of people and society. The church is not a community development organization- but the

development of community is essential to the church's nature.

So the more we thought about it, the more convinced we became of our need to search for a theology of mission that would give us new eyes to perceive our city, inform our activism, guide our networking, and energize our hope for the transformation of our city. In the months following the Los Angeles riots, our conviction has grown that such action-reflection (or reflective activism) is essential.

What is a theology of mission for the city?

In The Concise Dictionary of the Christian Mission, Gerald Anderson defined theology of mission as, "concerned with the basic presuppositions and underlying principles Which determine, from the standpoint of Christian faith,

the motives, message, methods, strategy and goals of the Christian world

mission" (Neill, Anderson and Goodwin 1971:594).

Theology of

mission is a multi - and interdisciplinary enterprise. It is a relatively

new discipline, with its first text appearing in 1961 in a collection of essays

edited by Gerald Anderson, entitled The Theology of Christian Mission (Anderson

1961). That volume clearly represented the tripartite nature of theology

of mission.

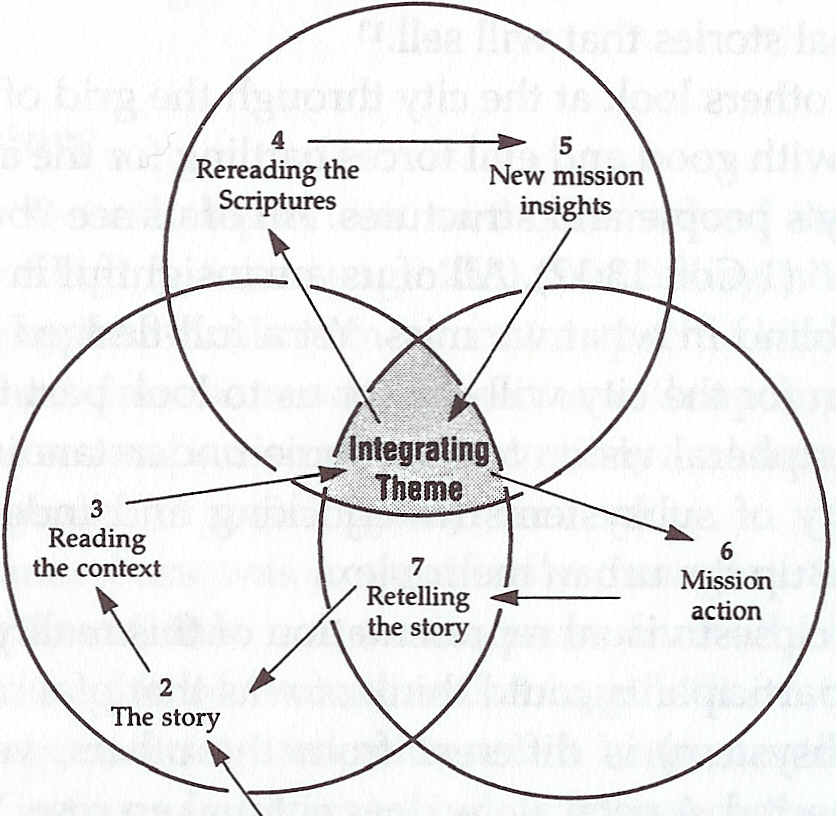

As shown in

Figure 5 on page 249, theology of mission has to do with three arenas, shown

graphically by three interlocking circles. We apply biblical and

theological presuppositions and values (1) to the enterprise of the church's

Figure 5: The tripartite nature of theology of mission

ministry and mission, and (2) set them in the context of specific activities carried out in particular times and places? First, theology of mission is theology (circle A above), because fundamentally it involves reflection about God. It seeks to understand God's mission, God's intentions and purposes, God's use of human instruments in God's mission,

and God's working through God's people in God's world.8 Theology of mission

deals with all the traditional theological themes of systematic theology-but it

does so in a manner that differs from the normal way systematic theologians operate.

The difference arises from the multidisciplinary missio- logical orientation of

its theologizing. In addition, because of its commitment to remain faithful to

God's intentions, perspectives, and purposes, theology of mission shows a fundamental concern for the relation of the Bible to mission. It attempts to allow Scripture to provide not only the foundational motivations for mission, but also to question, shape, guide, and evaluate the missionary enterprise.9

Second, theology of mission is theology of (circle C in Figure 5 on page 249). In contrast to much systematic theology,

here we are dealing with an applied theology. At times it looks like what some

would call pastoral or practical theology, due to this applicational nature. This type of theological reflection focuses specifically on a set of particular issues-those concerning the' Church's mission.

A person would find works dealing with the history of theology of mission1o that are not especially interested in the theological issues as such, but on their implications for mission activity. These works will often examine the various pronouncements made by church and mission gatherings (Roman Catholic, Orthodox, ecumenical, evangelical, Pentecostal, and charismatic) and ask questions-sometimes polemically-about the results of these for missional action.!1 The documents themselves become part of the discipline of theology of mission.

Third, theology of mission is specially oriented toward and for mission

(circle B in Figure 5 on page 249). We find the most basic reflection in this

arena in the many books, journals, and other publications dealing with the theory of missiology itself.12 We cannot allow either missiology or theology of mission, however, to restrict itself to reflection only. As Johannes Verkuyl stated,

Missiology may never become a substitute for action and participation. God calls for participants and volunteers in his mission. In part, missiology's goal is to become a "service station" along the way. If study does not lead to participation, whether at home or abroad, missiology has lost her humble calling. . . . Any good missiology is also a missiologia viatorum-"pilgrim missiology" (1978:6,18).

Theology of mission draws its incarnational nature from the ministry of Jesus, and always happens in a specific

time and place. Hence circle C involves the missiological use of all the social science disciplines that help us understand the context in which God's mission takes place. This book deals with probably the most complex context missiology has ever faced: the urban metroplex.

To begin to understand the city, first we borrow from sociology, anthropology, economics, urbanology, the study of Christianity and religious pluralism in the city, psycho- logical issues of urbanism, and a host of other cognate disciplines. When we do this type of macro analysis of the city, however, we immediately find ourselves pulled away from the here and now of the gospel's incarnational interaction with the people of the city.

Second, this makes us come to a more particular con- textual understanding of the city in terms of a hermeneutic of the reality in which we minister. Third, this in turn calls us to hear the cries, see the faces, understand the stories, and respond to the living needs and hopes of people. This made the seminar group understand that it needed to begin its reflection with stories. But a larger framework of the forces at work in the urban environment encompass the stories. Therefore, an interaction with the stories called us to rethink, to look again, to understand more deeply what went on at the macro level, as that affected the micro structures of the persons we encountered. Circle C involves a strong dialectical tension between seeing people's faces, and seeing those faces in their urbanized contexts.

As we can see in Figure 5 on page 249, the three circles overlap each other. It is not realistic to isolate any of the dynamics mentioned so far, because when urban life and urban ministry happen, they do so in the midst of all three circles at once. This fact slowly made itself felt to us. As our group became more familiar with the interaction of the three circles, we began to see that the complexity of the content of the issues of urban missiology forced us to adopt a specifically

multi- and interdisciplinary method for reflection and action. We

discovered that recognizing the necessity of dealing with both the complexity

and simplicity of life as it is in the city was our starting point for how

to construct a theology of mission for the city. We needed to deal

with the three arenas together, while simultaneously keeping them separate in

our minds.

HOW MAY WE CONSTRUCT A THEOLOGY OF MISSION FOR THE CITY?

In what follows I will give a brief summary of the steps that the seminar group

found helpful in constructing a theology of mission for the city. Clearly, this

is not the only way to do such reflection. Neither do these steps represent a

comprehensive treatment of the method.

In this section I intend only to highlight the broad parameters of what we discovered, allowing the reader to envision the process as it flowed through this book's preceding chapters. Each author intentionally constructed the preceding chapters to follow the process I am about to describe-- but the reader should take note that each chapter did so in a slightly different manner. This is because one of our most significant discoveries was that the manner in which the process applies to each given urban context is

itself

contextual.

In other words, we must transform not only the content, but also the method itself to fit critically and appropriately the particular issues, styles, agendas, and themes arising in each context.

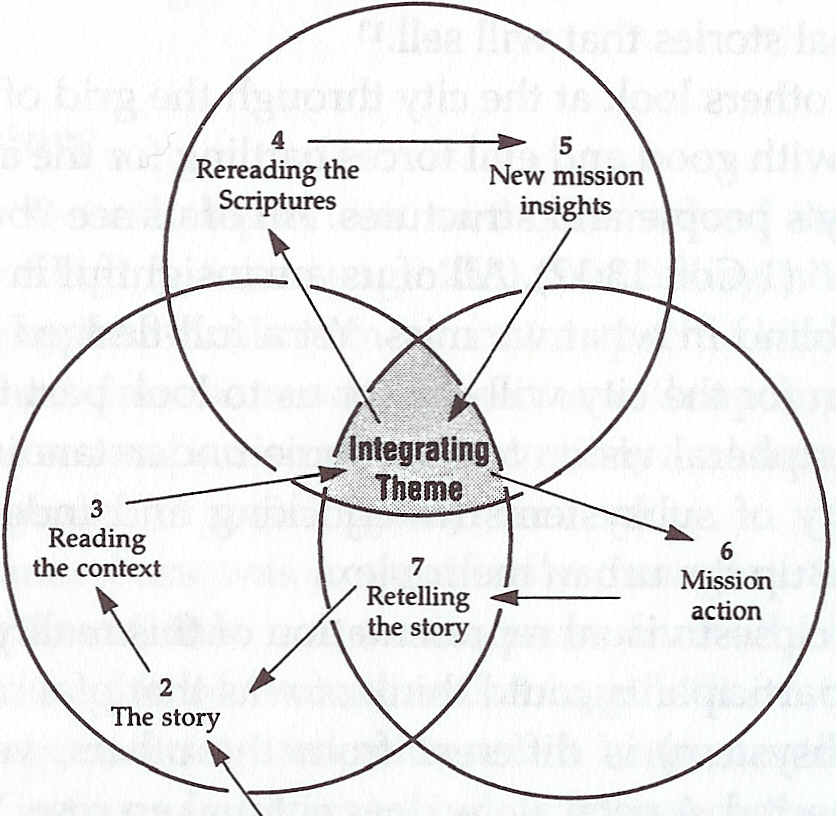

As we can see from Figure 6 on page 253, our method for constructing a theology

of mission for the city involved walking through the three multi- and

interdisciplinary circles we saw earlier, and adapting and contextualizing their contribution for a particular urban context. So being self- conscious and self-critical in approaching the city was the first step in our process.

Figure

6:

Methodological components of a

biblical theology of mission for the city

A Biblical Text

1

Setting the stage-approaching the city

B Faith Community

C Urban Context

Constructing a theology of mission for the city

1. Approaching the city

The earlier discussions in this chapter have already pre- pared us for the first step in our method. We begin-at the bottom of Figure 6 above-by setting the stage, asking about the perceptions, images, and lenses that we use to exegete the city. Some (primarily in the U.s.) would view the city as a series of concentric circles: a perspective that led to the language about "inner city" and "suburb." Others (primarily Europeans) might see the city in terms of "old town" and "new town." Persons from the Third World see the city as a central business district with surrounding "barrios," or "favelas," "districts," "cantonments," or " slums."

As the reader saw in several chapters, we may also view the city as a network of extended family relationships,

or as a compilation of ethnic subsystems. City planners see streets and buildings, politicians see voters, the police see violence, educators see schools, bankers and economists see businesses, and commuters see traffic. Television sees through a narrow, selected, and restricted lens, looking for sensational stories that will sell.13

Still others look at the city through the grid of spiritual warfare, with good and evil forces battling for the allegiance of the city's people and structures. All of us see "but a poor reflection" (1 Cor. 13:12). All of us are insightful in what we see, and blind in what we miss. Yet a full-fledged theology of mission for the city will call for us to look past the limits

J

of our peripheral vision to gain some understanding of the

complexity of subsystems (interlocking and independent) that make up the urban metroplex.

The closest visual representation of this reality that the seminar participants could think of was that of a rose. Each petal (subsystem) is different from the others, yet all are interconnected. A petal alone does not make a rose. Yet a rose cannot exist except as the sum of its petals. Also, a rose draws from a whole system of supports involving the rose- bush, just as a city draws from a host of supporting cultural, geographic, national, global, and historical elements that help to sustain the city.

Like a rose, the city also includes intangible elements of beauty and smell that

we cannot identify specifically with any given petal-it is the overlapping of

the various petals that gives each city its unique image. Like a rose, the city

is full of thorns and we must handle it carefully and gingerly. Finally, the

city is similar to a rose in its fragility. Cut a rose and it wilts quickly;

likewise in the city. As the reader saw in some chapters, life in the city is fragile; death is often too near.14

So the first step in our method involved a commitment to view the city systemically, holistically, and critically, while we searched for biblical values and insights to inform our

life and ministry in our cities. This in turn forced us to be willing to remain in touch with the complexity of the whole, while also keeping our feet grounded in the specificity of the here and now of persons living in the city. The easiest way to do this was to begin on the sidewalks of our cities by telling a story.

2. The story

The second step of our method involved standing in circle C of Figure 6 (see

page 253), and telling not just any anecdote or historical moment, but a

specific kind of story. Our method drew somewhat from the anthropological technique known as participant observation, and from the case study approach of sociology and counseling.

Because ours was a specifically theological task, how- ever, we found that our stories most fruitfully borrowed from the insights of "narrative theology." "Narrative theology" has been associated with recent hermeneutical developments

in the way biblical scholars approach the Bible. Yet the seminar group

discovered that the method itself contributed powerfully to seeing the macro issues of the city through the eyes of the micro concerns of persons.15

What we meant by this was a method that went beyond the purely historical, sequential retelling of an episode. At the other end of the spectrum, we also felt it necessary to stop short of a totally subjective approach that would ascribe to the event whatever meaning we might feel led to give it.

Instead, we searched for particularly appropriate stories that would serve as specific time and place windows to the larger macro structural issues that we could find high- lighted and illustrated by the story. As we saw the stories within the social, cultural, religious, relational, personal, and other urban issues of the original context, we would allow their meanings to illuminate our understanding of missio- logical praxis in the city.

As David Tracy put it, "Human beings need story, symbol, image, myth and fiction to disclose to their imaginations some genuinely new possibilities for existence: possibilities which conceptual analysis, committed as it is to understanding present actualities, cannot adequately provide" (Tracy 1988:207).

Alisdair MacIntyre recognized several diverse uses of narrative that we found echoed time and again in our reflection as a seminar. He argues that (1) intelligible human action is narrative in form; (2) human life has a fundamentally narrative

shape; (3) humans are storytelling animals; (4) people place their lives and

arguments in narrative histories; (5) communities and (6) traditions receive their continuities through narrative histories; and (7) the construction and reconstruction of more adequate narratives and forms of narrative mark epistemological progress (Hauerwas and Jones 1989:8).16

James Gustafson defines narrative in relation to its function, a use that echoed loudly in our own process.

Narrative functions to sustain the particular moral identity of a religious (or secular) community by rehearsing its history and traditional meanings, as these are portrayed in Scripture and other sources. Narratives shape and sustain the ethos of the community. Through our participation in such a community, the narratives also function to give shape to our moral character, which in turn deeply affects the way we interpret and construe the world and events and thus affects what we determine to be appropriate action as members of the community. Narratives function to sustain

and confirm the religious and moral identity of the Christian community, and

evoke and sustain the faithfulness of its members to Jesus Christ (Gustafson 1988:19-20).

The story selection was a critical step in our reflective process, because we

wanted to focus on the narratives that were representative of our ministries, central to our contexts, and rich in hermeneutical meaning far a deeper understanding of the cities in which they happened. We found that when the story was appropriate it naturally led us to broaden our perspectives, to see through it like a window that looked out beyond the event itself and helped us better understand the third step in the process: reading the context.

3. Reading the context

The third step of the process involves listening with new ears, seeing with new

eyes, allowing the city to influence the imagination in ways it is not used

to-thus yielding a new "hermeneutic" of the city. This use of the word

"hermeneutic" does not refer to deriving the meaning from the text of Scripture.17

Nor does this refer to reading the signs of the times,18 as was

common in the missiology of the World Council of Churches of the 1960s and early

1970s, when there was talk of letting the world set the agenda. Instead, this

type of hermeneutic involves rereading the context in terms of the

symbols, meanings, and perspectives that were there all along but to which we

may have been blind.19

Juan Luis Segundo's The Liberation of Theology (1976) is probably the

best methodological treatment of this type of hermeneutic. I would not espouse

the way Latin American liberation theologians reduced their hermeneutical method

to narrow socioeconomic and political agendas. Yet the process that Segundo

describes seems to have much to com- mend it for reflection on the new reality

facing us in today's cities.

Segundo outlined four decisive steps in the process of

the hermeneutical circle. First, we experience reality, which leads us to

ideological suspicion. Secondly, there is the application of our ideological

suspicion to our understanding of reality in general and to Scripture and

theology in particular. Third, we experience

a

new

way of perceiving reality that leads us to the exegetical suspicion that the

prevailing interpretation of the Bible has not taken important pieces of data

into account...

This calls for rereading the biblical text. Fourth, we develop a new

hermeneutic, that is, we find a new way of interpreting Scripture with the new

perceptions of our reality at our disposal. This leads us to look again at our

reality, which begins the process all over again (Van Engen 1993:31).21

The third step leads naturally into the fourth. After

looking at the urban context with new suspicions, new agendas and new eyes, we

raise our sights and find that we now have new questions to bring to Scripture

as well.

4. Rereading the Scriptures

The reader may see from Figure 6 on page 255 that the movement from step 3 to

step 4 is by way of an "integrating theme" that forms the central idea

interfacing all three circles. Because of the complexity of the inter- and multidisciplinary task, the seminar group found it helpful for each person to focus on a specific integrating idea that would serve as the hub through which to approach a rereading of Scripture. So the reader can quickly review the table of con- tents and see that each contribution to this book focused on one major concept that best reflected the author's contextual hermeneutic, and most profitably led to looking again at Scripture.

Clearly, we are trying to avoid bringing our own agendas to, and superimposing them on, Scripture. Liberation theologians made this mistake, and have not recovered from it. What we sought is a way to bring a new set of questions to the text, questions that might help us see in the Scriptures what we had missed before.22

This new approach to Scripture is what David Bosch called "critical hermeneutics."23

5. New mission insights

As we reread Scripture, we .face new insights, new values, and new priorities that call us to reexamine the motivations, means, agents, and goals of our urban missiology. This, in turn, calls us to rethink each of' the traditional themes of theology. Consequently, this will involve us in a contextual rereading of Scripture to discover anew what it means to know God in the city.

The nature of the city and the gods in the city, issues of creation and chaos in the city, revelation, Christology, soteriology, pneumatology, ecclesiology, and eschatology, for example, take on unique hues when colored by the city's realities. Robert McAfee Brown called this type of reflection, "Theology in a New Key" (1978), and "Unexpected News" (1984).

In Latin American theology, this theological process especially focused on issues of Christology and ecclesiology. In the city, it appears that we need to allow our rereading to offer us new insights into the scope and content of our missiology, derived from a profound rethinking of all the traditional themes of theology.24

6. Mission action

The move from step 5 to step 6 involves a movement from circle A to circle B (see Figure 6 on page 255). Due to the complex nature of the enterprise, it seems best to allow this step to flow again through the focus of the "integrating theme," which can help hold the various ideas together.

In 1987, the Association of Professors of Mission discussed at length what missiology is, and how it does its reflection. Referring to doing theology of mission, the Association members said that,

The mission theologian does biblical and systematic theology differently from

the biblical scholar or dogmatician in that the mission theologian is in search of the "habitus," the way of perceiving, the intellectual understanding coupled with spiritual insight and wisdom,

which leads to seeing the signs of the presence and movement of God in history,

and through his church in such a way as to be affected spiritually and

motivationally and thus be committed to personal participation in that movement. . . .

Such a search for the "why" of mission forces the mission theologian to seek to

articulate the vital integrative center of mission today. . . . Each formulation

of the "center" has radical implications for each of the cognate disciplines of the social sciences, the study of religions, and church history in the way they are corrected and shaped theologically. Each formulation supports or calls into question different aspects of all the other disciplines. . . . The center, therefore, serves as both theological content and theological process as a disciplined reflection on God's mission in human contexts. The role of the theologian of mission is therefore to articulate and "guard" the center, while at the same time to spell out integratively the implications of the center for all the other cognate disciplines (Van Engen 1987: 524- 525).

Conceptually, our involvement here is with something that the philosophy of

science calls "paradigm construction" or "paradigm shift."25 We know that a

paradigm shift is normally understood (especially in the philosophy of science) as a corporate phenomenon that occurs over a long period and involves the reflective community interacting with a particular issue. David Bosch, however, initiated many of us into seeing paradigm formation as a powerful way of helping us reconceptualize our mission concerning specific communities in specific contexts.

In these terms, a paradigm becomes" a conceptual tool used to perceive reality and to order that perception

in an

understandable, explainable, and somewhat predictable pattern" (Van Engen 1992:53). It i~ ~'an entire constellation of beliefs, values and techniques. . . shared by the members of a given community" (Kling and Tracy 1989:441-442). So a paradigm consists of "the total composite set of values, worldview, priorities, and knowledge which makes a per- son, a group of persons, or a culture look at reality in a certain way. A paradigm is a tool of observation, understanding and explanation" (Van Engen 1992:53).

On the one hand, the mission theologian for the city takes very seriously the biblical text as text

(circle A), and tries to avoid superimposing particular agendas on the text. It

is equally true, however, as Johannes Verkuyl has said, "if study does not lead

to participation. . . missiology has lost her humble calling" (VerkuyI1978:6).

So the move from circle A to circle B ,(see Figure 6 on page 253) is a movement from text to community. Through the focusing mediation of the integrating theme, we now restate the new insights gained from a rereading of Scripture as contextually appropriate missional orientations of the church in the city.

Experts have offered several different names to describe this process. David Moberg analyzed the "social functions and dysfunctions of the church" as a social institution (1962). On the other hand, Lesslie Newbigin spoke of the congregation as "a hermeneutic of the gospel" This meant that persons and institutions in the surrounding contextual' environment read the gospel through the mediation of the local church. "I confess that I have come to feel that the primary reality of which we have to take account in seeking for a Christian impact on public life is the Christian congregation" (Newbigin 1989:227).26

David Roozen, William McKinney, and Jackson Carroll developed one of the most creative ways to approach this matter in Varieties of Religious Presence (1984). This study examined ten different congregations in Hartford, Connecticut

(U.S.A.) The result yielded four "mission orientations": (1) "the congregation

as activist," (2) "the congregation as citizen," (3) the congregation as

sanctuary," and (4) "the congregation as evangelist" (Roozen, McKinney and

Carroll 1984).

These four characterizations do not exhaust the possibilities of describing

the missional dimensions, intentions, and relations of the communities of faith

- the church - within the city. It might be interesting for the readers,

however, to examine their own faith communities and discover how many

congregations and missional situations they can encapsulate within one of these

four missional orientations.

7. Retelling the story

The final, but at the same time initial, step in the process involves

suggestions for contextually appropriate, biblically informed missional action.

We called it "retelling the story," because this step brings us back to the here

and now of the person on the sidewalks of our cities. It also asks very

specifically about the actions within and without the faith community that it

must take to respond to the initial situation.

Here we find ourselves in the middle ground between biblically informed

missiological action and contextually appropriate mission action. If our

theology of mission does not result in informed action, we are merely "a

resounding gong or a clanging cymbal" (1 Cor. 13:1). The intimate

connection of reflection with action is essential for urban missiology.

Yet if our mission action does not itself transform our reflection, we may have

great ideas - but they may be of such heavenly import that they are of no

earthly good.

The seminar participants discovered that one of the most helpful ways to

interface reflection and action was through the process known as "praxis."

Although there have been several different meanings ascribed to this idea,27

we have found that Orlando Costas' formulation was very constructive for

us. "Missiology," Costas says,

"is

fundamentally a praxeological

phenomenon. It is a critical reflection that takes place in the praxis of

mission...[It occurs] in the concrete missionary situation, as part of the

church's missionary obedience to and participation in God's mission, and is

itself actualized in that situation....Its object is always the world... men and

women in their multiple life situations...In reference to this witnessing action

saturated and led by the sovereign, redemptive action of the Holy Spirit... the

concept of missionary praxis is used. Missiology arises as part of a

witnessing engagement to the gospel in the multiple situations of life (1976:8).

In The Praxis of Pentecost

(1991), Ray Anderson presents the concept of "praxis" in reflections on Jesus'

ministry he developed through the story of the woman caught in adultery (John

8:1-11). Based on the story, Anderson offers a hermeneutic of Jesus'

ministry as "a paradigm of Christopraxis" (!991:48). Following this

viewpoint, Anderson then speaks of Christ's "praxis of liberation," "praxis of

sanctification," and "praxis of empowerment" (1991:49-62).

The concept of "praxis" is

consistent with what we saw earlier in circle A regarding narrative theology.

It is consistent in the sense that not only the reflection, but also profoundly

the action, becomes part of the "theology on the way" of discovering how

the church may participate in God's mission in the city.

The action is itself

theological, and serves to inform the reflection, which in turn interprets,

evaluates, and projects new understanding in transformed action. The

interweaving of reflection and action offers a transformation of all aspects of

our missiological engagement with the city. This leads us back to a faith

commitment, a loving engagement

hopeful envisioning of ways in which we pray we may retell the story. So we return to where we began, and boldly proclaim the retelling of the story.

I saw the Holy

City,

the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And

I heard a loud voice from the throne say- ing, "Now the dwelling of God is with [people], and he will live with them. They will be his people, and God himself

will

be with them and be their God" (Rev.

21:2-3).

NOTES

1.

Please note that the reader can in no way construe these woes as anti-Semitic. On the contrary, they denounce the leaders of the people for misleading the Jewish nation that God cares for so deeply.

2.

See David Bosch, 1991, pp. 56-122.

3.

In "Biblical Perspectives on the City" (1992), Roger Green- way offered a provocative analysis of Jerusalem as an image of urban missiology, comparing Babylon and Jerusalem. Oddly enough, he omitted reference to this passage. See also John W. Olley, 1990.

4.

For example, James H. Cone, 1993; Cain Hope Felder, 1989; Shelby Steele, 1990; Robert Linthicum, 1991a, 1991b; Ray Bakke, 1987 (new edition, 1992); Benjamin Tonna, 1985; Larry Rose and Kirk Hadaway, eds., 1984; David Frenchak and Sharrel Keys, eds., 1979; David Frenchak and Clinton Stockwell, comps., 1984; Viv Grigg, 1984, 1992; Harvie Conn, 1987, Roger Greenway and Tnnothy Monsma, 1991; Roger Greenway, 1973, 1976, 1978, 1979, 1992; David Claerbaut, 1983; George Gmelch and Walter P. Zenner, 1988; Joel Garreau, 1991; Michael Peter Smith, ed., 1988; Harold J. Recinos, 1989; Elijah Anderson, 1990; William Whyte, 1989; John Gulick, 1989; William Pannell, 1992; Tex Sample, 1984, 1990; Eleanor Scott Meyers, ed., 1992; and other related works like Harvey Cox, 1965, 1984;

Jacques Ellul, 1970; Francis DuBose, 1978; David Shep- pard, 1974; Lyle Schaller, 1987; and Edgar Elliston and Tnnothy Kauffman, 1993. .

.

5.

Linthicum says, "Participation in community organization provides the church with the most biblically directed and most effective means for bringing about the transforma- tion of a community-through the assumption of respon- sibility by the community's residents to solve corporately their own problems" (1991b:109). For some years, Alfred Krass (1978) voiced this concern as well, apparently want- ing to keep evangelism, mission, community organization, and urban missiology together in a more integrated fash- ion. See also Donald Messer, 1992.

6.

See e.g., David Sheppard, 1974; Ralph Neighbour Jr., 1990; Del Birkey, 1988; C. Kirk Hadaway, Stuart A. Wright, and Francis M. DuBose, 1987; Lois Barrett, 1986; Bernard J. Lee and Michael A. Cowan, 1986; Robert and Julia Banks, 1989; and John Noble, 1988. It would be interesting to study the base ecclesial community movements in Latin America as possibly a new form of the church in an urban setting-but that is outside the scope of this book. The astounding multiplicity of small Pentecostal storefront churches found in cities all over the world is another well- known phenomenon that receives too little attention from those who study the church's ministry in the city. The megachurches that arose all over the world during the 1980s might have offered themselves as another new model for the church in the city~xcept few of them have shown any intention of contributing to the holistic trans- formation of the cities in which they are found.

7.

The three arena nature of this method is not original with me. Many others have highlighted something similar, par- ticularly those who deal with contextualization from a missiological perspective. See, for example, Eugene Nida, 1960; Louis Luzbetak, 1963; Jose Miguez-Bonino, 1975; Shoki Coe, 1976; Harvie Conn, 1978, 1984, 1993a, 1993b; Arthur Glasser, 1979; Charles Kraft, 1979, 1983; Charles Kraft and Tom WISely, eds., 1979; Bruce Fleming, 1980; John Stott and Robert Coote, 1980a; Paul Hiebert, 1978,

1987a, 1993; Robert Schreiter, 1985; C. Rene Padilla and Mark Lau Branson, 1986; Alan R. TIppett, 1987; R. Daniel Shaw, 1988; Dean Gilliland, ed., 1989; David Hesselgrave, 1989; Lamin Sanneh, 1989; Charles Van Engen, 1989; William Dyrness, 1990; Stephen Bevans, 1992; and Donald R. Jacobs, 1993.

8. See, for example, Daniel T. Niles, 1962; Georg F. Vicedom, 1965; John V. Taylor, 1972; Jbhannes Verkuyl, 1978:163-204; and John Stott, 1979.

9. See e.g., Robert Glover, 1946; G. Ernest Wright, 1952; J. H. Bavinck, 1977; Gerald Anderson, 1961; Harry Boer, 1961; Johannes Blauw, 1962; Roland Allen, 1962; Richard De Ridder, 1975; George Peters, 1972; Orlando Costas, 1974, 1982, 1989; John Stott, 1976; Lesslie Newbigin, 1978; J. Verkuyl, 1978, chapter IV; David Bosch, 1978, 1991, 1993; Dean Gilliland, 1983; Gailyn Van Rheenen, 1983; William A. Dyrness, 1983; Donald Senior and Carroll Stuhlmueller, 1983; Roger Hedlund, 1985b; Marc Spindler, 1988; Ken Gnanakan, 1989; Arthur Glasser, 1992; and Charles Van Engen, 1992, 1993. A combined bibliography drawn from these works would offer an excellent resource for examining the relation of Bible and mission.

10. See, for example, Rodger Bassham, 1979; David Bosch, 1980; James Scherer, 1987, 1993a, 1993b; Arthur Glasser and Donald McGavran, 1983; Arthur Glasser, 1985; Efiong Utuk, 1986; James Stamoolis, 1987; and Charles Van Engen, 1990.

11. See, for example, Donald McGavran, ed., 1972; Arthur P. Johnston, 1974; Harvey Hoekstra, 1979; Roger Hedlund,

ed., 1981; Donald McGavran, 1984; and David Hessel-

grave, 1988. One of the most helpful recent compilations of such documents is James A. Scherer and Stephen Bevans, 1992.

12. Examples of some readily accessible works would include J. H. Bavinck, 1977; Bengt Sundkler, 1965; Johannes Verkuyl, 1978; C. Rene Padilla, 1985; James Scherer, 1987; F. J. Verstraelen, 1988; David Bosch, 1980, 1991; James Phillips and Robert Coote, 1993; and Charles Van Engen,

Dean Gilliland and Paul Pierson; 1993. Clearly the most comprehensive work that willbe considered foundational for missiology for the next decade is David Bosch, 1991.

13. Concerning the Los Angeles riots of 1992, Los Angelenos generally believe that the media significantly contributed to making the riots worse than they would have been. The irresponsible television coverage almost invited additional looting and rioting.

14. At Lausanne n in Manila in 1989, Fletcher Tmk offered a "jungle-profile" view of the city that many found helpful. From its subterranean life, surface life, its small plants, lower canopy, middle canopy, and upper canopy, with its diurnal and nocturnal variations, and filled by its symbiotic systems-many aspects of a primeval jungle can be instructive for viewing modem cities.

15 For a discussion of this hermeneutical approach from sev- eral differing perspectives, see, e.g., Gary L. Comstock, 1987; David N. Duke, 1986; Gabriel Fackre, 1983; Michael Goldberg, 1981; Ronald L. Grimes, 1986; David M. Gunn, 1987; David Tracy, 1988; Stanley Hauerwas and L. Gre- gory Jones, eds., 1989; Paul Lauritzen, 1987; V. Philips Long, 1987; Alasdair MacIntyre, 1980; Kurt Mueller- Vollmer, ed., 1989; Richard Muller, 1991; and Grant Osborne, 1991.

16 Quoted by Les Henson, 1992, p. 19.

17 See, e.g., Luke 4:14-30; Luke 24: 27, 45; Acts 2:14ff; Acts

9:30-31; and Acts 15 as New Testament illustrations of this type of hermeneutic regarding the Old Testament. Paul's writings, Hebrews, and 1 Peter are also excellent places to investigate this.

18 See, for example, Matthew 16:1-12.

19 We may find examples of this in Numbers 13 and

Deuteronomy 1 (the differing reports of the spies regard- ing Canaan); Psahn 137:1 and Daniel 1:19-21 (the differing attitudes to being

20 "The idea of the 'hermeneutical circle' has been around since the early 1800's,.. . often associated with Friedrich Schleiermacher,

. . .

WIlhelm Dilthey, Edmund Husserl,

Martin Heidegger, Rudolf Bultmann, and Georg Gadamer, among others. But Latin American liberation theologians transformed the concept into an intentional, creative, and revolutionary methodology for contextual theology" (Van Engen 1993:30).

21 Besides Juan Luis Segundo, 1976, see also, e.g., Gustavo

Gutierrez, 1973; Jose Miguez-Bonino, 1975; Guillermo C@ok, 1985; Roger Haight, 1985; C. Rene Padilla, 1985; Leonardo Boff and Clodovis Boff, 1987; and Samuel Esco- bar, 1987.

Leonardo Boff and Clodovis Boff, 1987,8-9; Waldron Scott, 1980, XV; Leonardo Boff, 197?:~; Deane Ferm, 1986, 15; C. Rene Padilla, 1985, 83; Rebecca Chopp, 1986,36-37, 115- 117,120-121; Gustavo Gutierrez, 1983, 19-32; Clodovis Boff, 1987, xxi-xxx; and Gustavo Gutierez, 1984, vii-viii, 50- 60.

22 For a more in-depth discussion of this issue, with support- ing bibliographical comments, see Van Engen, 1993, pp. 27-36.

23 See David Bosch, 1991, pp. 20-24.

24 Harvie Conn gave us a summary form of just this sort of thing in 1993a, pp. 102-103.

25 See, e.g., Carl Hempel, 1965, 1966; Stephen Toulmin, 1961, 1972; Ian G. Barbour, 1974, 1990; Thomas Kuhn, 1962,

1977; James H. Fetzer, 1993a:147-178, 1993b; Hans Kiing and David Tracy, eds., 1989:3-33; and David Bosch, 1991:349-362.

26 The last chapter of Newbigin's

The Gospel

in a Pluralistic Society

contains some fascinating beginning points for a new reflection of what it could mean for the church to be intentional about its missiological orientation to the city. Newbigin highlights the local congregations as (1) a com- munity of praise, (2) a community of truth, (3) deeply involved in the concerns of its neighborhood, (4) prepared for and sustained in the exercise of the priesthood for the world, (5) a community of mutual responsibility, and (6) a community of hope.

27 See, e.g., Robert McAfee Brown, 1978, 50-51; Raul Vidales, 1975, 34-57; Gordon Spykman et al, 1988, xiv, 226-231; Robert Schreiter, 1985, 17, 91-93; Orlando Costas, 1976, 8-9;

Leonardo Boff and Clodovis Boff, 1987, 8-9, Waldron Scott, 1980, xv; Leonardo

Boff, 1979:3; Deane Ferm, 1986, 36-37, 115-117, 120-121; Gustavo Gutierrez,

1983, 19-32; Clodovis Boff, 1987, xxi-xxx; and Gustavo Gutierez, 1984, vii-viii,

50-60.